|

History

of Fort Duquesne

The French Fort Duquesne and the outlying

buildings in 1755.

The Struggle for Control of

the Fork of the Ohio

One of the defining characteristics of

Pittsburgh's place in the colonial history of the America is the

struggle that took place for control of the strategic fork of the Ohio River.

The French needed to establish themselves in the Ohio River Valley to

consolidate their holdings in New France (Canada), New Orleans and west of

the Mississippi River.

In the early-1700s, while the British

worked to establish their dominance on the eastern coast, the French were

busy setting up outposts and forts along the Great Lakes. By the 1740s, the

French began a drive south along the Allegheny River and Ohio River Valleys,

in a bid to extend the province of New France. Trading posts and settlements

were established and their claim to the region seemed secure.

The English had expansionist

thoughts of their own, and their reach soon stretched across the Allegheny

mountain range, to the west and into the French claimed territory. English

traders were soon setting up their own posts to barter with the local

tribes.

A commerce war soon followed, with the

English underbidding their French rivals. A short local conflict, known as King George's War, followed. It ended in 1748 with an uneasy truce that allowed the

English access to the Ohio and Mississippi River for trading purposes.

The French Claim The Ohio

Country

This agreement was deemed unacceptable

by the French monarchy. An expedition soon followed, led by Pierre-Joseph Celeron

de Blainville, in 1749. Leaden plates were buried in several locations throughout

the Ohio Valley officially claiming the lands for King Louis XV.

One of the lead plates buried by

Pierre-Joseph Celeron de Blainville.

Throughout their travels, the French were

disheartened to find that many of the Native Americans in the region were sympathetic to their English

trading partners. Because of this, they could not count on the full support of

the Six Nations in their efforts to oust the ever increasing number of traders.

The Indian tribes were divided in their loyalties, strategically allying

themselves with whichever side that gave them the best deal. Oftentimes, these

allegiances changed, depending upon the current circumstances.

To counter British ambitions, the

French began building a string of forts extending south from Lake Erie down

the Allegheny Valley. The first was Fort Presque Isle, on Lake Erie, in early

1753; followed by Fort Leboef, at French Creek, in December 1753; and Fort

Machault, along the Allegheny River, in April 1954.

As French dominance grew, they began

a policy of interdiction on British trade with the Indians. The French argued

that the traders were dealing weapons and contraband in an effort to incite

the local tribes to unite against their rule.

Virginia Governor Dinwiddie's

Ultimatum To The French

In 1747, the British colony of Virginia

formed the Ohio River Company to engage in land speculation and trade with

the local Indian tribes. Half a million acres of land, mostly on the south side of the Ohio River

between the Monongahela and Kenhawa Rivers, were granted. In 1752, an English

expedition moved into, and mapped, the Ohio Country west of the Allegheny

Mountains. In early-1753 plans for a fort and settlement along the Monongahela

River were prepared.

On October 31, 1753, 21-year old

Major George Washington, his guide Christopher Gist, and a small party set out from

Williamsburg to the nearest French outpost, at Fort Le Boeuf, near

Waterford, Pennsylvania. Washington carried Virginia Governor Dinwiddie's

warning to the French army, which the British felt had invaded the Allegheny

River Valley. The message was clear. The French were to abandon their

military occupation of the Ohio Country and withdraw.

On his way to meet with the French

commander, Washington's party passed by the junction where the Monongahela

and Allegheny Rivers meet to form the Ohio River.

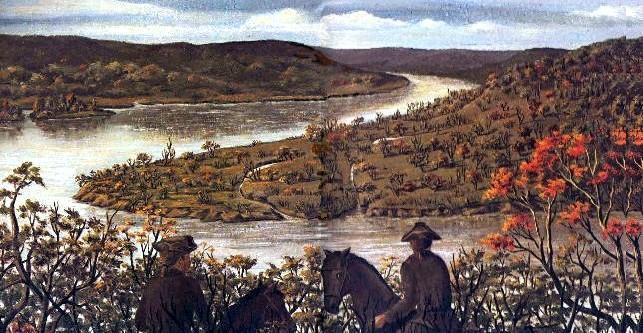

The fork of the Ohio River and the

site chosen by George Washington for a British Fort

Washington was impressed with the

nature of the terrain and the commanding position it presented. On November

24, 1753, he wrote in his journal:

"As I got down before the canoe,

I spent some time viewing the rivers, and the land in the fork, which I

think extremely well situated for a fort, as it has the absolute command

of both rivers. The land at the point is twenty-five feet above the common

surface of the water; and a considerable bottom of flat well timbered land

all around it very convenient for building. The rivers are each a quarter

of a mile across, and run here very nearly at right angles; Allegheny,

bearing north-east; and Monongahela, south-east. The former of these two

is a very rapid and swift running water, the other deep and still, without

any perceptible fall."

Map drawn by George Washington of the

Ohio Country in 1753.

"As I had taken a good deal of

notice yesterday to the situation at the intended fort, my curiosity led

me to examine this more particularly, and I think it greatly inferior,

either for defence or advantages, especially the latter. A fort at the

fork would be equally well situated on the Ohio, and have the entire

command of the Monongahela, which runs up our settlement, and is

extremely well designed for water carriage, as it is of a deep, still

nature. Besides, a fort at the fork might be built at much less expense

than the other place."

Washington and Gist arrived at

Fort LeBoeuf on December 11, 1753. The commandant, Jacques Legardeur de

Saint-Pierre, received Washington politely, but contemptuously rejected

Governor Dinwiddie's ultimatum, restating the French crown's claim to the

region.

Major George Washington and his guide

Christopher Gist cross the Allegheny River

after Washington's meeting with the French commander at Fort LeBoeuf.

Washington and Gist rushed back to

Williamsburg, and arrived on January 16, carrying to Dinwiddie a letter

containing the French commander's refusal to withdraw. Washington also

relayed his observations about the commanding nature of the land at the

forks. The Virginia Governor immediately made arrangements to send troops

of the colonial militia to fortify the river junction.

Tensions Escalate Over

The Fork Of Belle Riviere

One company, under the command of

Captain William Trent, was dispatched, and arrived at the fork on

February 17, 1754. Construction of a stockade, called Fort Prince George, was

begun. The French responded to this incursion by sending a force of sixty boats,

300 canoes, 500 soldiers and Indians, and eighteen artillery pieces to evict

the British garrison.

Captain Trent and his company at the river

junction.

On April 17, 1754, Monsieur

Claude-Pierre Pecaudy de Contrecoeur, Captain of a company of the French

Marine, delivered a summons to the British garrison, demanding their

immediate withdrawal. Captain Trent was away at Turtle Creek, and Ensign

Edward Ward was in command. With only forty men and an unfinished stockade,

there was no alternative but to abandon the area and retreat peaceably south

towards Virginia.

The French referred to the Ohio River

as the Belle Riviere. Control of the fork of the Belle Riviere was essential

to their plans to assert their dominance over the region. With the British

garrison gone, the French soldiers began construction of a much larger

structure, called Fort Duquesne. It was named after the Governor of Canada,

the Marquis Du Quesne de Mennville.

Marquis Du Quesne de Mennville

French plans for Fort Duquesne.

One of the bastions (left) and the

courtyard and main buildings of Fort Duquesne.

The French and Indian War

(1754-1763)

The English were already on the march to

reinforce the garrison at Fort Prince George with two additional companies of

Virginia militiamen, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Washington, when news reached them of Ward's capitulation. Undaunted, the

Virginia militiamen sought out the French with orders to engage. The opposing

forces met on May 28, 1754, in a skirmish known as the Jumonville Affair, or

the Battle of Jumonville Glen.

Washington's soldiers routed the French

unit, which consisted of 35 Canadians under the command of Captain Joseph Coulon

de Villiers de Jumonville. The French captain was captured and summarily executed

by Tanacharison, one

of Washington's native guides. This action set off a chain of events that

led to all-out war between the European powers for control of not only the Ohio

River Valley, but for all of colonial North America.

Fort Necessity, where George Washington

and 300 Virginians battled the French in 1754.

After the battle, Washington and his

men withdrew to Great Meadows. Fearing an attack, the Virginians immediately

began construction of a stockade. On July 3, 1754, the French responded in force.

A battle ensued between Washington's 300 Virginians and an attacking force of

600 French and 100 Indians, known as the Battle of Fort Necessity.

The colonial militia defended their stockade

against the French force in a driving rainstorm. Washington wrote:

"We continued this unequal fight with

an enemy sheltered behind trees, ourselves without shelter, in trenches full of

water, and the enemy galling us on all sides incessantly from the woods, until

eight o'clock at night."

Major George Washington and

his Virginia militia retreat from Fort Necessity in July 1754.

When the Virginians were unable

to continue the fight, Washington was compelled to sign a truce with the French

commander. The Virginians retreated from the fort with honors. The capitulation

was a bitter humiliation for the English, and plans were immediately launched to

retake control of the river junction. The French and Indian War had begun.

General Edward Braddock's

Defeat

In February of 1755, General Edward

Braddock, the supreme commander of British forces in North America,

and two regiments of troops from Ireland, along with colonial forces

including Colonel George Washington were raised to march on the French fort.

On May 29, 1755, Braddock's army

embarked from Virginia. By the 8th ofJuly they had reached the outskirts

of Fort Duquesne and prepared to march against it. The following day, while

advancing on the fort, they were ambushed by a force of 850 French and Indians

and suffered a devastating defeat, during which General Braddock was mortally

wounded.

General Braddock and his army traveled

from Virginia to the outskirts of Fort Duquesne.

The following eyewitness account of

the British defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755, is taken

from the King's Library Volume 212, as published in "The History Of

Pittsburgh," by Neville Craig, published in 1851.

The Monongahela had two extremely

good fords, which were very shallow, and the banks not steep. On the evening

of July 8, it was resolved to pass this river the next morning, and

Lieutenant Colonel Gage was ordered to march before the break of day, with

the two companies of Grenadiers, 160 rank and file, of the 44th and 48th,

Captain Gates' Independant Company, and two six pounders. He was instructed

to pass the fords of the Monongahela and to take post after the second

crossing, to secure the passage of that river.

Sir John St. Clair was ordered to

march at four o'clock, with a detachment of 250 men, to make the roads for

the artillery and baggage, which was to march with the remainder of the

troops at five.

Indian scouts watch as units of

General Braddock's army make their crossing of the Monongahela River.

On July 9th the whole marched

agreeably to the orders, and about eight in the morning, the General made

the first crossing of the Monongahela by passing over about 150 men in the

front, to whom followed half the carriages; another party of 150 men headed

the second division; the horses and cattle then passed, and after all the

baggage was over, the remaining troops which until then possessed the

heights, marched over in good order.

The General ordered a halt, and

the whole formed in their proper line of march. When we had moved about a

mile, the General received a note from Lieutenant Colonel Gage, acquainting

him with his having passed the river the second time without any

interruption, and having posted himself agreeably to his orders.

General Braddock and his aides cross the

Monongahela River.

When we got to the other crossing,

the bank on the opposite side not being yet made passable, the artillery and

baggage drew up along the beach, and halted until one, when the General

passed over the detachment of the 44th, with the pickets on the right. The

artillery wagons and carrying horses followed, and then the detachment of

the 48th with the left pickets, which had been posted during the halt upon

the heights. When the whole had passed, the General again halted until they

formed according to the annexed plan.

It was now near two o'clock, and

the advanced party under Lieutenant Colonel Gage, and the working party

under John St. Clair, were ordered to march on until three. No sooner were

the pickets upon their respective flanks and the word given to march, we

heard an excessive quick and heavy firing in the front. The General,

imagining the advanced parties were very warmly attacked, and being willing

to free himself from the incumbrance of the baggage, ordered Lieutenant

Colonel Burton to reinforce them with the vanguard, and the line to

halt.

French and Indian forces attack the

British during the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755.

According to this disposition,

eight hundred men were detached from the line, free from all embarrassments,

and four hundred were left for the defence of the artillery and baggage,

posted in such a manner as to secure them from any attacks or insults. The

General sent forward an aide-de-camp to bring him an account of the nature

of the attack, but the fire continuing, he moved forward himself, leaving

Sir Peter Halket with the command of the baggage.

The advance detachment soon gave

way, and fell back upon Lieutenant Colonel Burton's detachment, who was

forming his men to face a rising ground upon the right. The whole were now

got together in great confusion. The colors were advanced in different

places to separate the men of the two regiments. The General ordered the

officers to endeavor to form the men, and tell them off into small divisions,

and to advance with them, but neither entreaties nor threats could

prevail.

The advanced flank parties, which

were left for the security of the baggage, fled. Their baggage was them

warmly attacked, a great many horses and some drivers were killed, the

others escaped by flight. Two of the cannon flanked the baggage, and for

some time kept the Indians off; the other cannon which were disposed of in

the best manner, and fired away most of their ammunition, were of some

service, but the spot being so woody, they could do little or no

execution.

A map of General Braddock's Defeat

on July 9, 1755.

The enemy had spread themselves in

such a manner that they extended from front to rear, and fired upon every

part. The place of action was covered with trees and much underwood upon the

left, without any opening but the road, which was only about twelve feet

wide. At a distance of about 200 yards in front, and upon the right, were

two rising grounds covered with trees.

When the General found it

impossible to persuade them to advance, and no enemy appeared in view; and

nevertheless a vast number of officers were killed by exposing themselves

before the men, he endeavored to retreat them in good order; but the panic

was so great that he could not succeed. During this time they were loading as

fast as possible, and firing in the air. At last, Lieutenant Colonel Burton

got together about 100 of the 48th regiment, and prevailed upon them, by the

General's order, to follow him toward the rising ground on the right, but he

being disabled by his wounds, they faced about to the right and

returned.

General Edward Braddock lies mortally

wounded amidst the chaos of the battle.

When the men had fired away all

their ammunition, and saw the General and most of the officers wounded, they,

by one common consent, left the field, running off with the greatest

precipitation. About fifty Indians pursued us to the river, and killed

several men in the passage. The officers used all possible endeavors to stop

the men, and to prevail upon them to rally; but a great number of them threw

away their arms and ammunition, and even their clothes, to escape the

faster.

About a quarter of a mile on the

other side of the river, we prevailed upon near 100 of them to take post

upon a very advantageous spot, about two hundred yards from the road.

Lieutenant Colonel Burton posted some small parties and sentinels. We

intended to have kept possession of that ground until we could have been

reinforced.

The mortally wounded General Braddock

being led from the field after the battle.

The General and some wounded

officers remained there about an hour, until most of the men had run off.

From that place the General sent Mr. Washington to Colonel Dunbar, with

orders to send wagons for the wounded, some provisions and hospital stores,

to be escorted by the two youngest grenadier companies.

After we had passed the

Monongahela the second time, we were joined by Lieutenant Colonel Gage, who

had rallied nearly 60 men. We marched all that night and the next

day.

General Edward Braddock

Of the 1300 men Braddock led into battle,

456 were killed and 422 were wounded. Officers were prime targets and suffered

greatly: out of 86 officers, 26 were killed and 37 wounded. General Braddock

died of his wounds on July 13, four days after the battle, and was buried on

the military road near Fort Necessity. The French reported very few

casualties.

The following is a list of officers

killed or wounded during Braddock's defeat:

The defeat of General Braddock's army

was the most disastrous affair to befall the British colonies. It laid open

large portions of the territory of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia to

the ravages of the Indians. The French and their allies were now

in complete control of the region. It would be three years before the

British once again had the strength to challenge their adversaries for

control of the Ohio River Valley.

Many of the survivors of Battle of the Monongahela who would go on to play pivotal roles in the

American Revolution years later were engaged in the action and gained some

experience in the art of war. General Gage, who subsequently commanded the

British army at Bunker Hill, led the advance party at Braddock's Field.

Horatio Gates, the conqueror of Burgoyne, Daniel Morgan, the hero of

Cowpens, and the gentleman who would lead the American Revolutionary Forces

and go on to become the first President of the United States of

America, George Washington, all served under General

Braddock.

British Colonel George

Washington

The fate of the British prisoners

captured by the Indians during the Battle of the Monongahela, or simply Braddock's Defeat, was far worse

than that of their surviving comrades. Twelve British regulars were brought

back to Fort Duquesne along with booty from the battle. These men were

tortured and burned alive on the banks of the Allegheny River.

British colonial soldier James Smith,

already a prisoner at Fort Duquesne, witnessed the gruesome spectacle. His

account is documented below in the slaughter at Fort Duquesne.

The

Slaughter At Fort Duquesne - July 10, 1755

Point State Park is a beautifully

landscaped greenspace and recreational area that sits at the junction of

the three rivers. The park rests at the forefront of the Golden Triangle,

and is one of the signature vistas of the City of Pittsburgh.

Historical markers are placed at

various locations throughout the park detailing the significance of the

area during the colonial era, when the two great European powers, France

and England, fought for supremacy in North America.

During wartime, atrocities are committed

and rarely documented. One such occurence was witnessed, and it happened

right on the banks of the Allegheny River, where spectators today gather

to watch the boat races at the Three Rivers Regatta. It is a macabre

tale of the torture of British prisoners at the hands of the

French-allied Indians.

James Smith was a member of General

Edward Braddock's advance party of construction engineers during the

ill-fated British drive against French-held Fort Duquesne in 1755.

A Pennsylvania native, Smith's tale of his time as a prisoner of the Mohawk

tribe at Fort Duquesne is both gruesome and fascinating. The following is

an excerpt from "The History Of Pittsburgh," by Neville Craig, published

in 1851:

In the spring of the year 1755,

James Smith, then a youth of eighteen, accompanied a party of three hundred

men from the frontiers of Pennsylvania, who advanced in front of Braddock’s

army, for the purpose of opening a road over the mountain. When within a few

miles of Bedford Springs, he was sent back to the rear to hasten the progress

of some wagons loaded with provisions and stores for the use of the wood

cutters.

Having delivered his orders, he

was returning, in company with another young man, when they were suddenly

fired upon by a party of three Indians, from a cedar thicket which skirted

the road. Smith’s companion was killed on the spot; and although he himself

was unhurt, his horse was so much frightened by the flash and report of the

guns as to become totally unmanageable. After a few plunges Smith was thrown

violently to the ground. Before he could recover his feet, the Indians sprang

upon him, and, overpowering his resistance, secured him as

prisoner.

One of them demanded, in broken

English, whether “more white men were coming up,” and upon his answering in

the negative, he was seized by each arm and compelled to run with great

rapidity over the mountain until night, when the small party encamped and

cooked their suppers. An equal share of their scanty stock of provisions was

given to the prisoner, and in other respects, although strictly guarded, he

was treated with great kindness.

On the evening of the next day,

after a rapid walk of fifty miles through cedar thickets, and over very rocky

ground, they reached the western side of the Laurel mountain, and beheld, at

a little distance, the smoke of an Indian encampment. His captors now fired

their guns and raised the scalp halloo! This is a long yell for every scalp

that has been taken, followed by a rapid succession of shrill, quick, piercing

shrieks - shrieks somewhat resembling laughter in the most excited

tones.

They were answered from the Indian

camp below by a discharge of rifles, and a long whoop, followed by shrill cries

of joy, and all thronged out to meet the party. Smith expected instant death at

their hands as they crowded around him; but, to his surprise, no one offered

him any violence. They belonged to another tribe, and entertained the party in

their camp with great hospitality, respecting the prisoner as the property of

their guests.

The French Fort Duquesne

On the following morning Smith’s

captors continued their march, and on the evening of the next day arrived at

Fort Duquesne - now Pittsburgh. When within a half a mile of the fort they

again raised the scalp halloo, and fired their guns as before. Instantly the

whole garrison was in commotion. The cannons were fired, the drums were beaten,

and the French and Indians ran out in great numbers to meet the party and

partake of their triumph.

Smith was again surrounded by a

multitude of savages, painted in various colors, and shouting with delight;

but their demeanor was by no means as pacific as that of the last party he had

encountered. They rapidly formed in two lines, and brandishing their hatchets,

ramrods, switches, etc, called aloud for him to run the gauntlet.

Never having heard of this Indian

ceremony before, he stood amazed for some time, not knowing what to do. Then

one of his captors explained to him that he was to run between the two lines

and receive a blow from each Indian, as he passed, concluding his explanation

by exhorting him to “run his best,” as the faster he ran the sooner the affair

would be over.

The truth was very plain, and young

Smith entered upon his race with great spirit. He was switched very handsomely

along the lines for about three-fourths of the distance, the strikes only acting

as a spur to greater exertions. He had almost reached the extremity of the line,

when a tall chief struck him a furious blow with a club upon the back of the head,

and instantly felled him to the ground.

Prisoner James Smith runs the gauntlet

outside Fort Duquesne.

Recovering himself in a moment, he

sprung to his feet and started forward again, when a handful of sand was thrown

in his eyes, which, in addition to the great pain, completely blinded him. He

still attempted to grope his way through, but was again knocked down and beaten

with merciless severity. He soon became insensible under such barbarous treatment,

and recollected nothing more until he found himself in the hospital of the fort,

under the hands of a French surgeon. He was beaten to a jelly, and unable to move

a limb.

Here he was quickly visited by one of

his captors, the same who had given him such good advice when about to commence

his race. He now inquired, with some interest, if he felt “very sore.” Young

Smith replied that he had been bruised almost to death, and asked what he had

done to merit such barbarity. The Indian replied that he had done nothing, but

that it was the customary greeting of the Indians to their prisoners, something

like the English “how d’ya do,” and that now all ceremony would be laid aside,

and he would be treated with kindness.

Smith inquired if they had any news of

General Braddock. The Indian replied that their scouts saw him every day from the

mountains, that he was advancing in close columns through the woods (this he

indicated by placing a number of red sticks parallel to each other, and pressed

closely together), and that the Indians would be able to shoot them down

“like pigeons.”

Smith rapidly recovered, and was soon

able to walk upon the battlements of the fort, with the aid of a stick. While

engaged in this exercise, on the morning of July 9th, he observed an unusual

bustle in the Fort. The Indians stood in crowds at the great gate, armed and

painted. Many barrels of powder, balls, flints, etc., were brought out to them,

from which each warrior helped himself to such articles as he

required.

They were soon joined by a small

detachment of French regulars, and the whole party marched off together. He

had a full view of them as they passed, and was confident that they could not

exceed four hundred men. He soon learned that it was detached against Braddock,

who was now within a few miles of the Fort; but from their great inferiority in

numbers, he regarded their destruction as certain, and looked joyfully to the

arrival of Braddock in the evening, as the hour which was to deliver him from

the power of the Indians.

In the afternoon, however, an Indian

runner arrived with far different intelligence. The battle had not yet ended when

he left the field; but he announced that the English had been surrounded, and

were shot down in heaps by an invisible enemy; that instead of flying at once or

rushing upon their concealed foe, they appeared completely bewildered, huddled

together in the centre of the ring, and before sundown there would not be a man

of them alive.

This intelligence fell like a

thunderbolt upon Smith, who now saw himself irretrievably in the power of the

savages, and could look forward to nothing but torture or endless captivity. He

waited anxiously for further intelligence, still hoping that the fortune of the

day might change. But, about sunset, he heard at a distance the well known scalp

halloo, followed by wild, quick, joyful shrieks, and accompanied by long continued

firing. This too surely announced the fate of the day.

A war party raises the scalp

halloo to announce their victorious return to Fort Duquesne.

About dusk, the party returned to the

Fort, driving before them twelve British regulars, stripped naked, and with their

faces painted black, evidence that the unhappy wretches were devoted to death.

Next came the Indians, displaying their bloody scalps, of which they had immense

numbers, and dressed in the scarlet coats, sashes and military hats of the officers

and British soldiers. Behind all came a train of baggage horses, laden with piles

of scalps, canteens, and all the accoutrements of defeated army.

The savages appeared frantic with joy,

and when Smith beheld them entering the Fort, dancing, yelling, brandishing their

red tomahawks, and waving their scalps in the air, while the great guns of the

Fort replied to the incessant discharge of the rifles, he says that it looked as

if hell had given a holiday, and turned loose its inhabitants upon the upper

world.

The most melancholy spectacle was the

band of prisoners. They appeared dejected and anxious. Poor fellows! They had but

a few months before left London, at the command of their superiors, and we may

easily imagine their feelings at the strange and dreadful spectacle around them.

The yells of delight and congratulation were scarcely over, when those of vengeance

began.

The prisoners, all British regulars,

were led out of the Fort to the banks of the Allegheny, and to the eternal

disgrace of the French commandant, were there burnt to death, with the most awful

tortures.

Smith stood upon the battlements and

witnessed the shocking spectacle. A prisoner was tied to a stake, with his hands

raised above his head, stripped naked, and surrounded by Indians. They would

touch him with red hot irons, and stick his body full of pine splinters, and set

them on fire; drowning the shrieks of the victim in the yells of delight with

which they danced around him.

His companions in the mean time stood in

a group near the stake, and had a foretaste of what was in reserve for each of them.

As fast as one prisoner died under his tortures, another filled his place, until

the whole of them had perished. All this took place so near the Fort, that every

scream of the victims must have rang in the ears of the French commandant!

Two or three days after this shocking

spectacle, most of the Indian tribes dispersed, and returned to their homes,

as is usual with them after a great and decisive battle. Young Smith was demanded

of the French by the Mohawk tribesmen to whom he belonged, and was immediately

surrendered into their hands.

Frontiersman and adventurer James Smith

(1737–1814)

After his experiences at Fort Duquesne,

James Smith was eventually adopted by a Mohawk family, ritually cleansed, and

made to practice tribal ways. Smith ultimately gained respect for Indian

culture before escaping near Montreal in 1759. He returned to the Conococheague

Valley in Pennsylvania and took up farming.

During Pontiac's War, he fought in the Battle of Bushy Run and later accompanied British

officer Henry Bouquet's 1764 expedition into the Ohio Country. Smith represented

Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, at the 1776 Constitutional Convention, and

when the American War of Independence broke out, he joined the Pennsylvania

militia with the rank of Colonel.

Smith moved to Westmoreland County in

1778. By the late 1780s, he and his family had relocated to Bourbon County,

Kentucky. There he served as a member of the Kentucky General Assembly for a

number of years. James Smith, the farmer, soldier, Indian captive, frontiersman,

adventurer and politician, passed away in 1814.

General John Forbes Marches

on Fort Duquesne

After their victory over the British

at Braddock's Field, the French consolidated their hold on the region that

was now firmly in their grasp. During this time, the war raged in other parts

of the country, but at Fort Duquesne there were no further large-scale military

actions. Small frontier skirmishes with the Indians, often attributed, correctly

or not, to Le Generale Washington, were the only engagements.

The English, however, were determined

to return in force and drive the French from the Ohio River Valley. Capturing

Fort Duquesne was the key to this goal. Control of the river junction would

threaten the French hold on the entire Northwestern frontier. To this end,

in the summer of 1758, a force of 6000 regular and colonial troops marched

on Fort Duquesne, under the command of General John Forbes.

General John Forbes

The Battle of Fort

Duquesne

In September of 1758, the vanguard of

Forbes Army were within a few miles of Fort Duquesne. On September 11, 1758,

Major James Grant led over 800 men to scout the territory around Fort Duquesne

in advance of the arrival of General Forbes' main column. The fort was believed

to be held by 500 French and 300 Indians, a force too strong to be attacked by

Grant's detachment.

Grant's party were within two miles of

the fort on September 13. A small party of fifty men were sent forward to scout.

They encountered no enemy outside the fort. They raided and burned a storehouse,

then returned to the main position. Major Grant, believing there were only about

200 enemy soldiers present, determined that the fort could be taken by

coup-de-etat and planned an attack to commence before the morning

sunrise.

The French and Indians ambush the British

at the Battle of Grant's Hill.

Thus, on September 14, before the sun rose

to the east and while the defenders of the fort still slept, Grant divided his force

into several parts. A company of the 77th approached the fort with drums beating

and pipes playing as a decoy. Two detachments numbering 350 men lay in wait, 250

on the Monongahela side of the fort and 100 on the Allegheny side, to ambush the

enemy when they responded to the ploy. Several hundred more were concealed near the

baggage train in the hope of surprising an enemy attack there.

The French and Indian force turned out to

be much larger than expected, and their response was swift and decisive. They

overwhelmed the small decoy force and overran the ambush positions to either side

of the fort. Other natives quickly moved to out-flanked the British position on

Grant's Hill. The attackers retreated in disarray and fled to the aid of the those

left at the baggage train. The Indians, concealed by thick foliage, unleashed a

heavy and destructive fire that could not be returned with any effect.

Private Robert Kirkwood of the 77th Regiment

as he is taken prisoner after the battle.

Private Robert Kirkwood of the 77th

Highland Regiment was pursued by four Indians and wounded. He later wrote that,

"I was immediately taken, but the Indian who laid hold of me would not allow

the rest to scalp me, tho' they proposed to do so. In short, he befriended me

greatly."

Many others were not so fortunate.

During the Battle of Fort Duquesne the British and Colonial soldiers suffered

342 casualties, of whom 232 were from the 77th Regiment. Major Grant, along

with Private Kirkwood and seventeen other rank and file soldiers, were taken

prisoner. The remainder of Grant's force escaped to rejoin the main army camped

at Fort Ligonier. The French and Indian defenders suffered only eight killed and

eight wounded.

Although Major Grant was subsequently

paroled and Private Kirkwood lived to write his story, the fate of several

other prisoners was brutally similar to their predecessors three years before during the Braddock Campaign. These soldiers were

tortured and mutiliated by their Indian captors, and their severed heads lined up

on posts outside the fort.

Major James Grant

Note: A plaque on the Allegheny County

Courthouse, erected in 1901, commemorates the site of the Battle of Fort Duquesne. The hill where the battle was fought is today

called Grant Street in downtown Pittsburgh. Here is a link to an online book

from Historic Pittsburgh, printed in 1934, detailing the Story of Grant's Hill, including Major Grant's epic failure at the

engagement outside Fort Duquesne on the evening of September 13/14,

1758.

The French Abandon Fort

Duquesne

General Forbes was gravely ill

during the campaign, and he trailed behind the column of soldiers and the

laborers who were constructing the military road. When he finally arrived at

Fort Ligonier in early November, the campaign season was practically

over. Major Grant's disastrous defeat and the coming of winter caused

doubt over whether his army should move on the fort immediately or wait until

following spring.

George Washington, now a General and an assistant to Forbes, had his Indian scouts

dispatched to gather intelligence on the condition of the fort. News of a

recent peace treaty with the Iroquois and Delaware Indians was heartening.

However, Forbes held a council of war on November 11, and decided to postpone

the attack.

Indian scouts allied with the advancing

British army provided intelligence on the French forces.

The next day, after receiving a report

from Washington's scouting party, Forbes reversed himself. The French at Fort

Duquesne were in dire straits. Most of the Indians had abandoned the post

after routing Grant's force in September. The French commander, Francois-Marie

le Marchand de Lignery, was left with a dwindling garrison. They had not

received any supplies in months. His soldiers were starving and had

resorted to eating their horses. The majority of the garrison was weak

and unfit for service.

The British set out at once, and as

the column neared Fort Duquesne, Lignery ordered the buildings burned and the

bulk of the munitions destroyed. The approaching soldiers could heard the

explosions from ten miles away.

The next day, November 25, 1758, General

Forbes' troops overtook the ruins of the once mighty French fort without meeting

any resistance. The French soldiers had quietly retreated to Fort LeBoeuf. Great

Britain had reclaimed the Forks of the Ohio.

It had been over four years since the

small British garrison at Fort Prince George had been evicted by the French.

Forbes' victory was celebrated throughout the American colonies and back home

in England. It was a devastating blow to French colonial aspirations.

General Forbes takes notes after the

fall of the French Fort Duquesne.

General John Forbes renamed the site

"Pittsborough" after Prime Minister William Pitt. When he began the arduous

journey back to Philadelphia, Forbes left Colonel Hugh Mercer in command.

The British garrison initially constructed a temporary structure, called

Mercer's Fort, and in 1759, began construction on Fort Pitt, an elaborate fortification built to withstand any

assault and assure British dominance in the Ohio Country.

In July 1759, while Colonel Mercer

and his troops were protected only by the small Mercer's Fort, preparations

were being made to drive the British once more from the fork of the Belle

Riviere. Seven hundred French soldiers and several hundred Indians, along

with cannons and provisions, gathered near Venango.

Before they could begin their task,

news of the British attack on Fort Niagara forced them to abandon their

plans and rush to the aid of that vital Great Lakes bastion. If Fort

Niagara fell, the entire French Northeastern colonial empire would

be in jeopardy.

Although the war between England and

France would continue for another four years, there was no further military

action between the two European adversaries near the forks of the Ohio

River. Pittsburgh was, however, a vital staging ground for numerous military

expeditions against the western Indians, and in 1763 was, for three months,

held under siege during the Indian uprising known as Pontiac's War.

Note: Mercer's Fort stood at the

site of what is today a parking lot between Point State Park and the

Pittsburgh Post Gazette building.

Fort Duquesne - 250

Years After Forbes Victory

The outline of Fort Duquesne is boldly

illustrated on the lawn at Point State Park, shown here in 2008.

|