|

A 1946 postcard image showing the city of Pittsburgh,

including the Wabash Railroad Bridge and elevated terminal complex.

History

of the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway

* Last Modified

- June 25, 2021 *

The Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway Bridge

stretches over the Monongahela River into downtown Pittsburgh in 1907.

The Final Piece In A

Grand Dream

The Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway

was the final piece in the grand dream of railroad baron Jay Gould and his son

George. The Gould's envisioned a single corporation with an transcontinental

railroad system to move freight from coast to coast. For several years, they

had acquired numerous independant lines, gradually expanding their reach westward

from the Pacific Ocean towards their east coast lines.

By the turn of the century, most of the

pieces were in place. The key to achieving this dream was building a

connecting line through Pittsburgh. The coast to coast system would then be

complete. This connecting line would be known as the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway.

As an independant railroad, the story of

the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway is one of poor planning, corporate

competition, bad luck, numerous disasters and one man's stubborn determination

to forge ahead against all odds. The Wabash opened for business in 1904 and,

despite high hopes of success, was bankrupt just four years later.

The legacy of the short-lived Wabash

Pittsburgh Terminal Railway endures to this day as one of Pittsburgh's hard

luck stories. However, the long-term legacy of the Pittsburgh connection built

by the Gould's continues to this day with the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad, a

successful independant interstate line that utilizes the old Wabash routes

to the south of Pittsburgh.

Much of the local line, including the

the Rook Yard and tunnel in Greentree, the Bigham Cut, the bridges and tunnels

along Saw Mill Run and Library Road, and the Castle Shannon Viaduct are much as

they were when constructed over a century ago. The sounds of the Wheeling & Lake

Erie locomotives as they skirt the borders of the Brookline community on their

way south towards Castle Shannon are a daily reminder of the once lofty

aspirations of Jay and George Gould.

The Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railway

A Transcontinental System

... By Any Means Necessary

Starting with investments in small

railroads in New York, Jay Gould began to amass a network of connecting

lines that was to eventually span the entire length of the country. Gould

first acquired the Erie Railroad in New York state, and in the west, the Union Pacific Railroad, Kansas Pacific Railway and Missouri Pacific Railroad.

Upon his death in 1892, Jay Gould's

railroad empire was passed on to his eldest son, George, a ruthless businessman

who continued consolidating and building the system. He acquired the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad and then the Western Pacific Railroad, completing the line from the Mississippi River

to the Pacific port of San Francisco.

Jay Gould (left) and his son George

were determined to create a single corporation

with a transcontinental railroad. In 1904 that dream became a reality.

Only four years later their corporation fell into bankruptcy.

George Gould's competition for the western

freight business was the Southern Pacific Railroad. In an example of the

underhanded business practices that became his trademark, he formed a company

to build a breakwater in San Francisco Bay. This created valuable new land

in the harbor area, but left the Southern Pacific terminal high and dry.

Gould then built a track atop the breakwater to his new Western Pacific

terminal, usurping his rival's access to ocean freight.

East of St. Louis, Gould acquired

the Wabash Railroad, providing a connecting branch as far east

as Toledo, Ohio. To complete the transcontinental system, Gould now needed

a connecting line to link the Wabash Railroad in Toledo with the Western Maryland Railway in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, which ran

through to the port of eastern port of Baltimore.

This final piece of the coast-to-coast

system was intended to run through the great industrial and freight center of

Pittsburgh, and would be called the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway. At

the turn of the century, more freight was shipped through Pittsburgh than any

other city in the United States, including the port of New York.

The route of the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway, from Zanesville OH to Connellsville PA.

In 1901, Gould acquired the Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad, extending the western line from Toledo to Zanesville, Ohio. The

Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway was then created by piecing together several

independant railroads south and east of Pittsburgh. From the east, he extended his

reach by acquiring Soutwestern Pennsylvania lines, including the Little Saw Mill Run Railroad and the West Side Belt Railroad in Pittsburgh. With these acquisitions the gap between Zanesville

and Connellsville had almost completely been covered.

All that remained was the construction

of two extensions, one that would connect his Western Pennsylvania holdings with

the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad in Ohio, and another to bring the railroad

directly to a depot in downtown Pittsburgh. These grandiose projects required

upgrading the existing local lines and extending them into West Virginia and

Ohio, construction of several bridges, viaducts and tunnels, and the building

of a major terminal complex in Pittsburgh.

Little did George Gould know at the time,

but the technical difficulty of building a railroad into Pittsburgh, where all

of the good routes had already been utilized, the massive costs of the construction,

the fierce competiton that developed with established rivals like the Pennsylvania

Railroad, and his increasingly speculative business practices, were a recipe for

disaster.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

The Little Saw Mill Run

Railroad

Abraham Kirkpatrick Lewis (1815-1860)

began mining on the face of Mount Washington about 1843. Lewis built one of the

earliest inclined planes, just west of the Duquesne Incline, for carrying coal

to the Monongahela River. He built the first tunnel through Mount Washington, a

distance of one mile, that led to the Saw Mill Run Valley.

To serve his mines along this valley,

he constructed a two mile long horse-drawn tramway, called the Horse

Railroad, which delivered coal to a tipple at the mouth of Saw Mill Run Creek

on the Ohio River. Soon the line was extended to the Little Saw Mill Run

Valley in Banksville. This early railroad was eventually replaced by a new

steam powered railroad.

A steam locomotive of the Little Saw Mill

Run Railroad.

The Little Saw Mill Run Railroad Company

was incorporated July 23, 1850, and the line opened in April 1853. From the

river docks near Temperanceville (West End) on the Ohio River, the narrow-guage

railroad followed Saw Mill Run Creek upstream to Shalersville (outside of the

present-day Fort Pitt Tunnels).

From this point, also known as

Banksville Junction, it turned to follow the present course of Banksville

Road along Little Saw Mill Run Creek. The adjacent Banksville Avenue was

the only roadway at that time. Only short sections of it remain today.

The railroad line continued along Banksville Avenue to the coal mining

town of Banksville located at Potomac Avenue.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

The West Side Belt

Railroad

In the 1890s, The Pennsylvania Railroad

had control over most freight shipments in and out of Pittsburgh. In a move to

raise the rates, traffic was slowed to a near standstill with shipments laying

idle throughout the area. Industialist Andrew Carnegie decided to do something

to end the difficulties with the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Carnegie purchased the Pittsburgh,

Shenango & Lake Erie Railroad, then extended and modernized the line for

heavier traffic, creating the Bessemer & Lake Erie Railroad. He further

hinted that he was intending to construct another line southeast to

Baltimore.

In 1895 George Gould saw his opportunity.

He noted that the Western Maryland Railway in the east and the Wheeling and

Lake Erie Railroad in Ohio could be used as part of his proposed transcontinental

system.

The West Side Belt Railroad was incorporated on

July 26, 1895 in Harrisburg, with the stated purpose of transporting coal over standard

gauge rails from Clairton to the Ohio River docks in Temperanceville (West End). The

railway would also engage in passenger and freight service, both to and from the city

of Pittsburgh.

The president was James Callery and the majority

shareholder was John Scully. Rumors quickly began circulating that the the railway

was intended as the local trunk line in George Gould's dream of a transcontinental

Wabash system with a hub in the highly competititive Pittsburgh market.

The West Side Belt acquired the existing Bruce

& Clairton Railroad and the Little Saw Mill Run Railroad, which already had an

established line to the tipples and river docks where the coal barges waited. The

twenty miles of connecting track (from Banksville to Monongahela City) between these

two existing systems would be constructed through West Liberty, Reflectorville,

Fairhaven and Castle Shannon.

The Little Saw Mill Run Railroad Company was

incorporated July 23, 1850. From the river docks near Temperanceville (West End), the

narrow-guage road followed Saw Mill Run upstream to Shalersville (outside of the

present-day Fort Pitt Tunnels). From there followed the course of Little Saw Mill Run

to the coal mining town of Banksville, at present-day Potomac Avenue.

♦ History of the West Side Belt Railway ♦

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

AN INVESTOR'S DREAM

The route through the South Hills to West Mifflin

was originally laid out by the B&O railroad when that system opened its Wheeling and

Finleyville Division, but never laid down.

The West Side Belt purchased the route, which

had at most a 1.5% grade and averaged only one percent. The greatest curve was just eight

degrees. Chief engineer J. H. McRoberts secured the property rights-of-way.

By 1897, the initial twelve miles of the route

had been surveyed, and there was some discussion about whether the line should an

electrified or conventional steam railway.

There was no debate, however, regarding the

potential untapped riches that lie along the railroad route in the form of black

gold. It was an investor's dream. The region was estimated to have 40,000,000 tons

of the finest bituminous coal in the world.

This coal was in high demand in Europe, and

the West Side Belt Railroad ensured that the product would now be placed on the

market. Prospects for success were so high that the company purchased over 10,000

acres of rich coal land along the railroad route.

Construction of a new railroad line, with

direct access to Pittsburgh, was expected to be a boon to development along the route.

Castle Shannon projected a 100% increase in property valuations, and there was an

increase in home construction in towns like Fairhaven (Overbrook).

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

THE DIRECT CONNECTION

On February 1, 1898, the railroad was purchased

outright by John Scully, president of the Diamond National Bank. Bonds were issued to

fund the continuing modernization of the Little Saw Mill Run Railroad, including the

construction of a 1000-foot trestle in Temperanceville to provide LSMRRR cars with a

direct connection to both the P&LERR and the Panhandle Railroad.

An interesting anecdote regarding the now defunct

Little Saw Mill Run Railroad, pointed out in the November 21, 1899, Pittsburgh Daily Post

was that the railroad line had a gradual ascent nearly all the way. It was not unusual

to a car loaded with passengers heading inbound through the Banksville corridor to the

West End without an engine or motor of any kind. Gravity did all the work, with a

conductor continually applying the brake.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

THE WABASH RAILROAD

As the 19th century drew to a close, talk

persisted that the West Side Belt was being designed solely to carry George Gould's

Wabash rail traffic into the city center. These discussions now involved a tunnel

through Mount Washington, and a railroad bridge over the Monongahela River to Ferry

Street. Engineers were already working on the preliminary stages of the

tunnel.

This arrangement would give partnering systems

like the Bessemer Railroad, and the Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad, a direct connection

to downtown Pittsburgh, challenging established giants like the Pennsylvania Railroad

and the B&O for a share of the lucrative Pittsburgh market.

These rumors were soon substantiated when Gould

officially announced his plans to extend his Wabash Railroad into the heart of the city

via the Wabash-Pittsburgh Terminal Railway. The West Side Belt Railroad was to be the trunk line

leading to the Wabash Tunnel and Bridge, then to an elevated freight/passenger platform

and terminal building downtown.

In April 1902, the West Side Belt Railroad

Company, along with all accumulated land holdings, was absorbed into a new corporation

called the Pittsburgh Terminal Railroad and Coal Company.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

LEGAL CHALLENGES

Construction of the West Side Belt line was

not without its share of difficulties. Legal challenges by competing railroads,

troubles with the terrain, and protests by landowners caused delays.

One particular dispute developed with the

nearby Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad. Both railroads followed the Saw Mill Run corridor, running adjacent to each

other for a portion of the way. The P&CSRR sued the West Side Belt for encroachments in

two locations were their routes ran parallel.

At Oak Station, along Oak (Whited) Street

in Reflectorville, the

P&CSRR had a mining operation and rail yard. The West Side Belt attempted to erect

a trestle it was alleged would interfere with the station's proper

operation.

Further down the line, in Castle Shannon, the

West Side Belt had to construct a long viaduct that ran over the P&CSRR line. Again,

it was alleged that one of the concrete supports interfered with the operation of the

line.

The West Side Belt's Castle Shannon Viaduct

running over the light rail lines which follow the former P&CSRR route.

Despite the concern over operational safety,

at the heart of the dispute were the rights to the lucrative coal fields and the

shipment of the mined product. A decision by Judge Marshall Brown in July 1902 to

dismiss the case was a major victory that cleared the way for the completion of the

West Side Belt Railroad.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

A TOUCH OF IRONY

Historically, this was not the first time that

the two competing railroads went head-to-head, literally. In May 1878, the Little

Saw Mill Run Railroad and the P&CSRR were involved in a dispute that resulted in

the conflict known as the "Castle Shannon Railroad War".

The Hays estate at 1900 Whited Street, shown

here in the 1920s. Once a rest stop along the railroad line, this 1850s-era

home has seen many changes over the years. The railroad tracks

run along the hillside behind the house.

In a touch of local irony,

the president of both of the antagonist railways, the P&CSRR and the Pittsburgh

Southern (which leased the Little Saw Mill Run Railroad), was Milton Hays, who grew

up in the home at 1900 Whited Street, in what was then Lower St. Clair Township.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

THE LANDAU INCIDENT

A notable incident with a property owner

occurred in early-August 1902, when the Landau Brothers, owners of a strip of land

at the bottom of Lang (Pioneer) Avenue at West Liberty Avenue. The contractors were

forced to cede nearly one-third of their property for the railroad right-of-way and

the relocation of the lower portion of the roadway.

When railroad construction crews arrived to

begin grading the property in question, which required a hillside cut and creating

a short abutment to reach the West Liberty Avenue railroad bridge. Although having

legally obtained the right-of-way from the borough a few years back, the owners were

displeased with the encroachment and the reported stand-off developed.

After some tense exchanges, construction

eventually finished their work and the property matter between the Landau Brothers

and the railroad was somehow settled.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

A PROFITABLE LINE

The South Hills portion of the railroad,

construction of which began in June 1901, was completed by September 1902. The entire

West Side Belt Railroad line, from the Ohio River docks to Clairton, was fully

modernized and operational by the summer of 1904.

Once in business, the West Side Belt became

one of the more profitable line in the Wabash-Pittsburgh Terminal Railway system. In 1909, the West Side Belt Railroad line was

upgraded to handle heavier locomotives and increasing freight traffic.

The West Side Belt Railway Company was part of

a December 1916 reorganization that resulted in the creation of the Pittsburgh and

West Virginia Railway Company, headquartered in Wellsburg, West Virginia. The P&WVRR

purchased the West Side Belt Railway outright in December 1928.

Constructing the Wabash

Pittsburgh Terminal Railway

The Braincild of Joseph

Ramsey

John Ramsey was the vice-president of

Gould's Wabash Railroad in the late 1890s. Born on Pittsburgh's South Side and

a graduate of the Western University of Pennsylvania on the North Side, he

was the driving force behind Gould's decision to make a move into the

highly competitive Pittsburgh market. While Gould's dream was to create a

Transcontinental System, it was Ramsey's dream to bring the railroad into

the city of Pittsburgh.

Joseph Ramsey

Ramsey formulated the

route of the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway. He convinced Gould of

the feasibility of the Pittsburgh extension and received both Gould's

financial backing and political clout. Ramsey quietly began surveying

and buying the necessary land needed to build the railroad.

Construction began in 1900 on the

initial 39.3 mile stretch of the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway, extending

westward from the outskirts of Pittsburgh towards the Wheeling & Lake Erie

Railroad. Good news came on February 1, 1901, when Andrew Carnegie signed

tonnage contracts for his steel operations with the Wabash, thereby ensuring

the railroad would receive a sizable portion of the lucrative Pittsburgh

shipping market.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Political Pressure From

Gould's Competitors

At the time Gould set his sites on the

Pittsburgh region, competition in the Pittsburgh market was already

dominated by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad,

the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad and several other regional lines.

These railroads had long since secured all of the obvious routes for access

into the city. Their executives exerted extreme political pressure and

influence to impede the approach of Gould's Wabash connection from the

Midwest.

Gould was no stranger to such tactics.

As the court battles and council meetings raged on, he continued building.

His engineers confidently began tunneling through Mt. Washington and building

the piers for a new bridge over the Monongahela, which would bring the line

into downtown Pittsburgh. After two years of political wrangling and back

door dealing, the shrewd Gould was able to gain enabling ordinances

from local officials. This allowed Gould to complete the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway in 1904.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Constructed In Three

Phases

Construction of the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway was completed in three phases. In September 1902, the southern

and western portions of the line were completed. This section required the

construction of numerous small bridges and trestles. Between the new freight

marshalling yards in Greentree and the 600-foot Mount Washington,

engineers carved out a curved course that required the building two tunnels,

the Greentree Tunnel and the Bigham Tunnel.

An aerial view showing the Rook Marshalling

Yard and the path of the Greentree tunnel.

The second phase included the construction

of a third tunnel. This was a major cut through the heart of Mount Washington,

from a southern portal near Woodruff Street to the northern portal on the downtown

side. The Wabash Tunnel was

completed in February of 1903.

The Wabash Tunnel, constructed in

1903.

The third phase of construction included

building the railroad's large, elevated nine-track terminal complex in downtown

Pittsburgh, stretching from Front Street to the Depot Building at Liberty Avenue

and Ferry Street, with a spur switch line extending to Duquesne Way.

Map of the Wabash Terminal Complex in

downtown Pittsburgh.

Also to be constructed was a bridge spanning

the Monongahela River to connect the elaborate downtown terminal with the tunnel.

The 14,000,000 pound span measured 812 feet. At the time it was the longest railroad

bridge in the country and third longest in the world, a status it held until

1909. Bridge construction was completed in February 1904.

The Wabash Railroad Bridge and Terminal

Complex in 1907.

On July 4, 1904, while the Depot building

was in the final states of construction, the first train of the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway left Pittsburgh as a special excursion to the St. Louis World's

Fair. The ornate terminal and office building opened in 1905. Joseph Ramsey's dream

of a Pittsburgh railroad hub and George Gould's vision of a transcontinental

corporation were a reality.

The ornate Wabash Terminal Building

opened in 1905.

Gould Went A

Bridge Too Far

One Disaster After

Another

Despite the high hopes of owner

George Gould and engineer Joseph Ramsey, the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railroad seemed doomed from the start. Gould's shady dealings had mobilized

the other railroads against him. His many competitiors did whatever they

could to deny him access to their markets. When Andrew Carnegie sold his

steel company to J.P. Morgan, the previously negotiated freight contracts

with Carnegie Steel were nullified. As a result, Gould's grand railroad

was never able to turn a profit.

Business failures aside, the railroad

was also plagued with a string of disasters that earned it the title

of "Pittsburgh's Hard Luck Railroad" before the line ever went into

operation. During construction of the line through Greentree in 1902, the

wooden interior of the Bigham Tunnel caught fire. The collapsed debris were

removed and the passage rebuilt as an open cut.

The Wabash Bigham Cut, to the right

of the Parkway, was once a tunnel that collapsed in 1902.

The Bigham Tunnel setback paled in comparison

to the events of October 19, 1903.This

was the day that the final piece of the bridge was to be set in place over the river.

Both ends jutted out from the banks, and as a crane hoisted the final girders into

place, disaster struck. The crane came loose and sent steel, wood and several helpless

workers plunging into the river below. The disaster took the lives of ten

workers.

Additional distractions like a smallpox

epidemic among the workers, strikes, riots and flooding caused further

hardships. Finally, the financial Panic of 1907 devastated the Gould fortune.

Within a year he was forced to sell off many of his railroad holdings, and

the dismantling of his vast empire began.

A Somber Look

Into Pittsburgh's Wabash Past

October 19, 1903 - A Disastrous Day

Pittsburgh's Hard Luck

Bridge

This is an article by

Joe Bennett that appeared in a Pittsburgh Press Roto addition

on September 5, 1977 entitled "Pittsburgh Bridges Falling Down."

When they finally tore down the Wabash

Bridge in 1948, nobody was sorry to see it go. The 812-foot railroad span seemed

to live under a curse from the beginning, perhaps haunted by the ghosts of the men

who died building it 45 years before.

By the time it was dismantled, it had

become a useless, dead skeleton hanging over the Golden Triangle. When the job

was done, Roto magazine ran a cover photo showing the "new look" of Downtown

Pittsburgh without the old eyesore.

The Wabash's sorry history began in 1902

when railroad entrepreneur George Gould commissioned its construction as part of

what would be his transcontinental system.

Pittsburgh, then the nation's freight

capital, generating more traffic than New York, Chicago and Philadelphia combined,

was to be the crown jewel of the Gould empire, but he had to fight to get it. The

Pennsylvania Railroad was financially and politically entrenched here, and Gould

spent millions just to remove the obstacles local politicians threw up.

Gould's bridge, linking his new terminal

on Water Street to the Wabash Tunnels through Mount Washington, loomed 109 feet

above the Monongahela River. Its construction was costly in lives as well as

dollars.

The morning of October 19, 1903, was a key one

for the bridge project. The two ends of the bridge, being built from opposite sides

of the Mon, were to be joined that day.

Supply barges were maneuvered into position

in the river, and cranes on the bridge started hauling steel up. Earl Crider, on

one of the barges, helped hook five beams to ropes from a crane. Later he described

what happened:

"There was an awful crash over our heads.

Looking up I saw beams and girders in the air. Then it seemed that the entire part

of the bridge extending out over the water had begun to fall. I had only an instant

to see all this. Then I jumped into the water. I was hit on the side of the head

with a beam of wood, but the water saved me from being crushed."

Crider was one of the lucky ones. The carrier

supporting the crane had broken loose, catapulting toward the edge of the bridge.

Machinery, steel and men were crushed and swept off the bridge.

"They fell through the air like flies," said

John McTighe, who watched the disaster from Water Street. "The men were shrieking

and yelling as they fell. Some were clinging to pieces of iron and beams."

In all, ten men died. Seven had been on the

bridge, three on the barges below. Five others, including Crider, escaped by

jumping into the river. They may have been warned by the quick action of the

hoisting engineer, who sounded an emergency horn as soon as he saw what was

happening.

There were miraculous escapes, too. One

unidentified worker, swept off the bridge, made a convulsive midair grab for a

safety rope and hung there while the deadly steel cascaded around him. Then he

slid down the rope to a boat and joined in the rescue operation. Another man lay

semi-conscious on a beam at the very edge of the bridge. When he came to his

senses, he looked around, saw where he was, and scrambled to safety.

At least two men survived the 109-foot

plunge to the water. Thomas Shelley landed between two of the barges and suffered

only a leg injury. "My fall to the river was quick," he reported, "but I thought

a whole lot in that short time."

Rescue work, begun almost immediately,

was severely hampered by crowds of curious Downtown workers, who had flocked to

the river banks to watch the show.

The October 19 disaster was the worst in a

series of misfortunes that beset the Wabash job. Weather was a constant problem,

and a smallpox epidemic hit the workmen. There were strikes, riots, landslides

and floods.

Nor did things improve after the bridge

opened with much fanfare in 1904. Despite Pittsburgh's rich freight market, Gould's

railroad never made enough money to pay for itself. The line was an engineering

marvel, cutting straight through the worst terrain Western Pennsylvania could

present, with hardly a hill or a curve to mar the traveler's ride. But construction

had cost about $1 million a mile, and the Wabash never wrested control of the

market from the Pennsylvania.

The new Wabash Bridge in 1904. Note the Wabash

Tunnel to the left along Mount Washington.

Weekly Gazette Coverage

Of The Bridge Disaster

The October 20, 1903 Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette

reported on the accident. It was 8:30 the morning previous morning, and work was

proceeding on the Water Street side of the bridge. Five I-beams were being hoisted

from a barge in the river to the structural work of the bridge. The beams weighed

nearly nine tons and were being lifted using a traveler and boom.

When they had been drawn by the crane to a

point about fifty feet above the water, the rope bearing the great burden of metal

suddenly snapped. The same instant the jib staffs in the crane gave way. This

portion of the structure projects about sixty feet over the stream beyond the floor

construction of the bridge, and with a rasping, grinding sound the whole mass

pitched forward, hurling the workmen down into the barge as if they had been shot

from a catapult.

Tons of iron went with them. The men in the

barge were caught as if in the jaws of a trip-hammer. Under the great weight the

barge capsized and some of the men who were not killed outright were pinned under

the twisted beams and drowned. Some fell over 100 feet and struck on top of the

wreckage, escaping with terrible injuries. A few men struck the water and were

saved.

News of the disaster spread quickly through

the city, and patrol wagons and ambulances were followed down Water Street by

thousands of onlookers. Men employed on the opposite bank of the river quickly

boarded skiffs to assist in the rescue of their co-workers. Willing hands from

nearby towboats and other craft along the riverfront also gave prompt

assistance.

The traveler both after the accident (left)

and before the accident. Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette photo.

Soon mutilated bodies, still in death, were

carried out and laid on the wharf while the morgue wagons made hurried trips to

the dead house. The injured were quickly extricated and taken to nearby hospitals.

The crowd remained throughout the afternoon, and it took several hours to recover

all of the corpses.

As the sun went down bridge workers led by

"Spike" Kelly, hoisted a black flag that was attached to the pier near the accident

site. It fluttered in the breeze as the last body was recovered at 7:30pm. Later

that evening the towboat Little Fred pushed the stricken barge to the Smithfield

Street Bridge were it was raised with a dock hoist.

The names of the dead were William C. Kempton,

W. J. McLeod, George Wells, Clark L. Fleming, Frederick Solinger, Frank Dalby,

John R. Campbell, G. W. Keitlinger, Charles Simmons and Edward Morris. Those severely

injured were Aaron Fowler, William Jay, Adam Vosburg, Thomas Shelley and

Frank Hoover.

Officials of the American Bridge Company,

during their inspection the following day, blamed the accident on an insufficiently

braced Traveler. Heavy hog chains over the top of the traveler and boom may have

avoided the catastrophe. The brace of the boom, on the downstream side of the

traveler, had swung away from the upright, throwing the entire weight on the joint

above, which in turn broke the boom.

Bridgeworkers had a different story. They

felt that the traveler was not built for hoisting such heavy loads. Engineers

countered that the equipment was capable of handling much larger loads and that

the traveler used was more than sufficient. The accident surprisingly caused no

structural damage to the bridge itself.

The two sides of the Wabash Bridge come

together in November 1903.

A Coroner's Jury in November 1903, after

hearing testimony from bridgeworkers, engineers and management regarding the safety

of the traveler and the ropes used to hoist the beams, determined that the disaster

was purely accidental and no blame was placed on anyone. One thing everyone agreed

on was that there appeared to be a hex on the railroad venture itself, one that

became known as the "Curse of the Wabash."

Later publications listed the cause of the

traveler failure to be as such ... "while the traveler was working well within its

capacity, the lower chord of the cantilever truss collapsed and the over hang

revolved downwards against the bridge trusses. The only reason to which failure

can be ascribed is that the bottom chord of the overhang in the panel next to the

traveler tower had become injured a short time before by a blow, probably from the

2-ton steel ram used in driving pins. This blow apparently buckled some of the

lattice bars and forced the chord out of position. When it was subject to live load

the stress was greatly increased by the eccentricity and the member failed under a

static load."

The Wabash Bridge under construction on the

north shore (left) and the two travelers meeting in the middle.

Bankrupt in Four

Years

The Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railroad's major facilities included the Wabash Terminal, an ornate

eleven-story building, the Wabash Tunnels through Mount Washington, the

Wabash Bridge, a stone skew arch over Saw Mill Run near Woodruff Street

known as the Seldom Seen Arch, and another stone archway which serves

as a tunnel for Greentree Road near Chartiers Creek.

The nine-track elevated downtown

terminal complex was covered by a trainshed which extended from Forbes

Avenue to the Boulevard of the Allies. A switching trestle extended

across the Triangle to a location just short of Fort Duquesne

Boulevard. There was also the Greentree freight marshalling facility

known as the Rook Yard.

Although the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway opened with gala fanfare and high expectations, Gould's

dream of a transcontinental empire soon came crumbling down around him in

a sea of red ink.

The high cost of construction, over

$1,000,000 per mile, and the failure of promised freight contracts to

materialize kept the railway from being profitable. The only part of the

railroad to operate at a profit was the West Side Belt, due largely to its

mining connections. Soon the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway went

into bankruptcy.

The Wabash Enters

Receivership

The Western Maryland Railroad was

the first of Gould's properties to fail, entering receivership on March 5,

1908. The Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad and the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railway soon followed, in May of the same year. This ended through traffic

between Pittsburgh and Gould's western railroads.

The Wabash Bridge and Terminal Complex

in 1908, the year the railroad filed for bankruptcy.

The West Side Belt Railroad was

the first part of the Pittsburgh system to enter receivership. The Belt

Railroad was one of the few tangible assets that the Wabash Pittsburgh

Terminal Railway Company had to build upon in it's attempts to reorganize

and stay in business.

A burst of modernization along

the line led to the construction of much of the infrastructure that is

in place today along Saw Mill Run Creek in Brookline, Overbrook and

Castle Shannon. The bridges and tunnels were all rebuilt in 1909.

Workers on the West Side Belt line, along

Cadet Avenue in Brookline, in 1909 (left); A P&WVRR train hauling coal

along Saw Mill Run, across from Bausman Street, heading towards Castle

Shannon.

Although the West Side Belt

Railroad remained a profitable venture, these recovery attempts did

little to bring profitability to the struggling Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railway as a whole. In the end, George Gould lost all of his Pennsylvania

holdings, much of his railroad empire and a substantial amount of his

fortune.

After years of operation by its

receivers, the company was finally sold at foreclosure, in 1916,

and reorganized as the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railway.

The Wabash Bridge crosses the Monongahela

River to the Wabash Tunnel entrance in 1930.

Photos Of The Wabash

Railroad Bridge

The Wabash Railroad Bridge in 1905.

The Wabash Bridge stretches over a smokey South

Side to Mount Washington.

The Wabash Bridge heading into the terminal

complex in downtown Pittsburgh in August 1912.

A river boat under the Wabash Bridge.

The Monongahela River Wharf with the Wabash

Bridge in the background.

Riverboats line the north shore of the Monongahela

River on August 8, 1922, with the Wabash Bridge in the background.

The elevated platforms along the Wabash

Terminal Complex.

The Wabash Bridge in 1938.

Water Street and Liberty Avenue on August 16, 1943,

with the Wabash Bridge in the background.

The Wabash Bridge in 1945.

The Wabash Bridge stands as a bridge to nowhere

in 1947 after the terminal complex was removed.

The Wabash Bridge being dismantled in

1948.

Final Pieces Of Hard Luck

For The Wabash Railroad

In 1908, the Wabash was forced to go into

receivership, and in 1917, the local spur was absorbed by the Pittsburgh and West

Virginia Railroad. After 1931, passenger traffic was discontinued, and only freight

traffic moved through the elaborate Downtown terminal. Then, in 1946, fire destroyed

the terminal. The Wabash bridge became a useless hulk.

A plan to use the bridge and tunnel as part

of a mass transit system into the South Hills had been dropped. Somebody suggested

taking the bridge down and putting it up elsewhere. Finally, the old bridge was

scrapped and the steel melted down for use in the Dravosburg Bridge that was being

built in 1948.

The Pittsburgh aerial view above, taken in

1948, shows the Wabash Bridge during the dismantling of the span. The terminal

complex to the left had been removed the year before. All that remained was the

grand terminal building, which was eventually razed in 1955 during construction of

the Gateway Center complex.

The Pittsburgh

and West Virginia Railroad

New Era Of

Prosperity

The Wabash properties from Pittsburgh to

Zanesville OH were purchased in August 1916 and reorganized, in November of that

year, as the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad.

Under new ownership, the railroad began an

era of cooperation with the other major railroads in the region. The railroad was

included in plans for a proposed system that consisted of the Pennsylvania Railroad, New

York Central Railroad, B&O Railroad and the Erie Railroad.

Tracks of the P&WVRR pass under the

Timberland Avenue Bridge in 1918.

This was the last important railroad

built in the Pittsburgh area. The route laid out by Joseph Ramsey for the

Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway ran along the tops of the ridges, involving

difficult engineering problems.

Nearly 6% of the mileage of the line is on

bridges and 2% in tunnels. There are over 170 bridges of more than ten feet

in length and twenty-one tunnels. Of these, 151 bridges and eighteen tunnels

are on the mainline. The costs of maintaining the road were exceptionally

high.

Pittsburgh & West Virginia steam

locomotives at the Greentree Rook Yard.

Despite these challenges, the Pittsburgh

and West Virginia Railroad found success where the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railroad had found failure. One benefit of being on the high ground was that

freight shipments continued during times of flooding, when other railroards

were unable to operate. The new railroad consistently posted annual income

increases during the 1920s.

The Pittsburgh and West Virginia

Railroad acquired the West Side Belt Railroad in December 1928, and in

February 1931 the Belt Railroad was extended to Connellsville PA,

re-establishing the route once used by George Gould to connect to the

Western Maryland Railway.

The Depression years brought the first

operating losses. This situation was reversed by the increasing traffic during

World War II, which brought the railroad back to profitability. The railroad

continued to operate with a net profit until 1958.

The Curse Of The

Wabash

Some said that the Pittsburgh

Wabash was cursed. The railroad line had certainly seen its share of

tragedies over the years. As part of the Pittsburgh and West Virginia

Railroad, these misfortunes continued, as if the rails themselves

were under a dark spell.

In November 1925, a landslide

blocked the downtown portal of the Wabash Tunnels and severely damaged

the first approach span to the Wabash Bridge. In October 1931, due

to a lack of ridership, passenger service into downtown was

discontinued.

The Wabash Bridge over the Monongahela

River and the

terminal complex in downtown Pittsburgh in 1938.

The elaborate Pittsburgh terminal

facilities, stretching the width of the Golden Triangle at Stanwix Street,

continued to be used for freight transfers. Then on March 6, 1946, a

warehouse building caught fire. Flames soon spread to the railroad trestle

and parts of the Wabash terminal building. The damage sustained was estimated

at $200,000.

The Wabash elevated platform and terminal

building along Ferry (Stanwix) Street in 1908 (left) and

the terminal building at Third Avenue after the second 1946 fire.

Two weeks later, another fire

completely destroyed the Wabash Terminal and the trestle. The blaze spread

to and gutted eleven warehouses. This final disaster put the Pittsburgh and

West Virginia Railroad officially out of business in downtown

Pittsburgh.

The Wabash Terminal Complex being

dismantled in 1947.

The Wabash Bridge was dismantled and

melted down as scrap metal in 1948. What remained of the terminal complex,

including the landmark Wabash Terminal Building, were razed in 1955

to make room for the Renaissance I Gateway Center project. The superstitious were convinced

that these developments put an end to the curse of the Pittsburgh

Wabash.

The Wabash Terminal building being

razed in 1955.

The only remaining signs of the

Wabash Railroad in downtown Pittsburgh are the Wabash Tunnels on Mount Washington and two darkened bridge piers standing idly

along the banks of the Monongahela River. The aging piers stand as monuments

to the hard-luck legacy of George Gould and the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railway.

The Wabash Bridge piers have stood

idle since 1948. The top of the piers are often

decorated with multicolored banners attached to poles.

Acts

Of Sabotage In The South Hills

Whether it was the Curse of the

Wabash or just plain coincidence, there were two incidents in the South Hills

of Pittsburgh were saboteurs planned to use dynamite to destroy sections

of the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad's West Side Belt line. The first,

in Bethel Park near Coverdale, was successful. A second attempt, near Glenbury

Street in Overbrook, was foiled by a group of local teenagers. The following

articles provide the accounts.

From the

Washington Reporter (May 25, 1927):

Railroad Line

At Coverdale Is Blown Up

Ties and Rails

Hurled In All Directions By Dynamite Blast

Experienced Bombers Set

Off Explosion

More than 100 feet of the main line of

the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad was blown up by a dynamite explosion

early today, near Castle Shannon.

These and pieces of rail were hurled

in all directions and holes three feet deep were made along the road bed.

Service along the main line will probably not be resumed until late

today.

The blast has temporarily held up

hauling of coal from the Pittsburgh Terminal Coal company mine at Coverdale,

a non-union mine closely allied with the Pittsburgh and West Virginia

Railroad.

The dynamiting was evidently done by

one experienced in the handling of explosives.

<><><><>

From the Pittsburgh

Press (January 16, 1932):

Find Dynamite, Train

Is Saved

Four Overbrook Boys

Prevent Tragic Explosion On Railroad Tracks

Blowing up of a train at Overbrook

was averted last night when four boys found 56 sticks of dynamite on tracks

of the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad's West Side Belt

line.

A few minutes after the explosives,

sufficient to damage the entire neighborhood, had been removed, a train from

the Castle Shannon-Coverdale area sped over the rails.

Had the locomotive struck the dynamite

wide havoc would have been wrought, bomb and arson detectives

said.

The dynamite was found in a box about

forty feet from Frederick Street.

Jerome Seible, 17, of 2504 Vineland

Street; William Price, 18, Franklin Street; Lawrence McGrail, 19, of 123

Jacob Street, and Harry Tewell, 16, of 91 Glenbury Street stumbled over the

box while walking on the tracks about 8 p.m.

They saw the layers of dynamite sticks

and the sign, "Danger, dynamite 40 percent extra strength" on each

side.

Running to Overbrook Police Station, the

boys notified officers. Patrolman Conrad Dietz and Edward Brown went to the

scene and removed the dynamite. A few minutes later the train

passed.

Each of the sticks was one and one-quarter

inches thick and eight inches in length. The box was taken to the city detective

bureau, where it was found to bear the numbers 1CC14 and 28-35.

These were being checked as a clue

to the owner.

After each stick of explosive and it's

wrapper had been carefully soaked in water, all were replaced in the box, which

then was dropped into the Allegheny River from the Manchester

Bridge.

William Price, Lawrence McGrail, Harry

Tewell and Jerome Seibel show the spot where they found

fifty-six sticks of dynamite on the P&WV railroad tracks on January 15, 1932

in Overbrook.

The Norfolk and Western Railway

Takes Charge

By 1960 the Pittsburgh &

West Virginia Railroad operated 132 miles of road on 223 miles of track

That year the railroad reported 439 million net ton-miles of revenue

freight.

Pittsburgh & West Virginia Railroad

trains cross the trestle at Whited and Jacob Streets in Brookline,

March 1957.

On October 16, 1964 the Norfolk

and Western Railway, which had merged with the Wheeling & Lake

Erie Railway in 1988, leased the Pittsburgh & West Virginia. Then, in

May 1990, Norfolk and Western sold off most of the former Wheeling & Lake

Erie Railway, which was reorganized as an independant regional

carrier.

The newly formed Wheeling &

Lake Erie Railway acquired the lease to the former Pittsburgh & West

Virginia line. Today, the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad

exists only as the name of an investment trust responsible for the

collection of lease monies.

The Wheeling & Lake Erie

Railway is responsible for administration and maintenance the lines

formerly used by the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway, and later

the Pittsburgh & West Virginia Railroad. Since 1990, the railroad

has experienced a sustained period of success and stability.

The Wheeling and

Lake Erie Railway

The Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad

was established on April 6, 1871, a narrow gauge line between Norwalk, OH

and Huron, Ohio. The line was gradually expanded to the West Virginia coal

fields. The line became operational on May 31, 1877. However, the new road

was unable to attract regular traffic, or financing for expansion, and closed

within two years.

With investment by railroad financier

Jay Gould in 1880 and financial reorganization, the line was converted to

standard gauge and expansion within the state of Ohio began again. Service

from Huron to Massillon, Ohio was opened on January 9, 1882 and new lines

were constructed that eventually reached the Ohio River and Toledo. The

Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad also developed new docks on Lake Erie at

Huron that opened May 21, 1884. Transportation of iron ore from the Lake

Erie ports to steel plants in southeastern Ohio became a main source of

revenue.

The railroad became one of the main

pieces in George Gould's plan for a transcontinental network. The railroad

was tied to the Gould system until 1908, when financial difficulties forced

the dismantling of Gould's coast-to-coast system.

The Gould railroads were placed in

receivership, and from 1908 through 1916 the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad

returned to it's roots, transporting coal from West Virginia, and ores

from Lake Erie, to Ohio mills.

In 1910, the railroad began producing

locomotives at it's Brewster OH facility. It became one of the finest

production facilities in the country. The company rolled boilers and built

fifty of their own steam engines, something never tried by the larger

railroad companies.

Steam locomotives of the Wheeling

and Lake Erie Railroad in the 1940s.

In 1916 the former Wheeling & Lake

Erie Railroad was sold at foreclosure and rechartered as the Wheeling

& Lake Erie Railway. The railroad began a period of sustained growth

and stability. By At the end of 1944 the railroad operated 507 miles

of road and 1003 miles of track. That year it reported 2371 million net

ton-miles of revenue freight and similar success in passenger

traffic.

In 1949 the Wheeling and Lake Erie

Railway was leased to the Norfolk and Western Railroad, and in 1988 merged

into the Norfolk and Southern system. The railroad was dissolved in 1989

and the assets sold in 1990 to a group of investors who renewed the old

corporate name.

The new rail system was made up of

a combination of the former Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad, with an accompanying

lease of the Pittsburgh & West Virginia Railroad. The 576 miles of track,

combined with trackage rights acquired from Norfolk and Southern, encompassed

840 miles.

The company was restructured in

1994, and has since that time has enjoyed a new period of sustained growth.

The railroad now handles over 130,000 carloads per year and operates in Ohio,

Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Maryland. As of 2018, it is one of the

largest regional railroads in the country.

The Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway

currently handles steel and raw materials to and from five different mills,

aggregates from four different quarries, chemicals, industrial minerals,

including frac sand, plastic products, grain, food products, lumber, paper,

and petroleum products including natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica

operations. The company services over 500 customers.

The railroad's fifty-three locomotives

and 1,600 cars are kept in working order at the company's updated locomotive

and car repair facility in Brewster OH.

♦ Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway Company Website

♦

The Wheeling and

Lake Erie Railway in Brookline

Though the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railroad ended operations in 1908, the railroads which were built around

Pittsburgh continued on under new ownership. The Pittsburgh and West Virginia

Railroad operated most of the local lines once owned by Gould. Later they were

acquired by the Norfolk & Western Railroad, and subsequently sold in the

formation of the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway, which operates the former

Wabash Pittsburgh and West Side Belt lines today.

Trains of the Wheeling and Lake Erie

Railway still run daily along the border of Brookline, in the South Hills

of Pittsburgh, on their way east and west. For local rail enthusiasts in

Pittsburgh's South Hills, the railroad is a great way to experience a piece

of the city's glorious railroad past.

A measure of the success of the

Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad can be guaged by the number of trains churning

their way up the 1.5% grade along Saw Mill Run and Library Road. Where there

was once one or two trains a day, there are now up to five trains making the

4.5 mile uphill climb towards Castle Shannon each day.

A video of a Wheeling & Lake Erie

Railroad train thundering past Whited Street in Brookline.

Along the line, from Greentree to

Castle Shannon, are many impressive and lasting vestiges of the Wabash

Pittsburgh Terminal Railway that are still in use. These include the

Greentree Rook Marshalling Yard, the railroad bridge over the Parkway

West, the one-mile Greentree Tunnel, the historic Seldom Seen Arch, the trestles at West Liberty Avenue and Edgebrook Avenue,

the Castle Shannon Viaduct, and the many vehicle tunnels along the way,

at Overbrook School, Glenarm Street, McNeilly Road, Kilarney Road and

Sleepy Hollow Road. All of these historic sites are over a century

old.

There is also the infamous Wabash Tunnel, which has been refurbished for vehicle use to ease traffic

congestion during the morning and evening rush hours.

Photos Of The

Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad In Brookline

Four photos of Wheeling and Lake Erie

trains passing over the trestle at Whited Street in Brookline.

Four photos of Wheeling and Lake

Erie trains at locations along Jacob and Ballinger Streets in Brookline.

Photos Of The

Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad In Greentree

The Rook Freight Marshalling Yard

in Greentree continues to be a busy place for rail traffic.

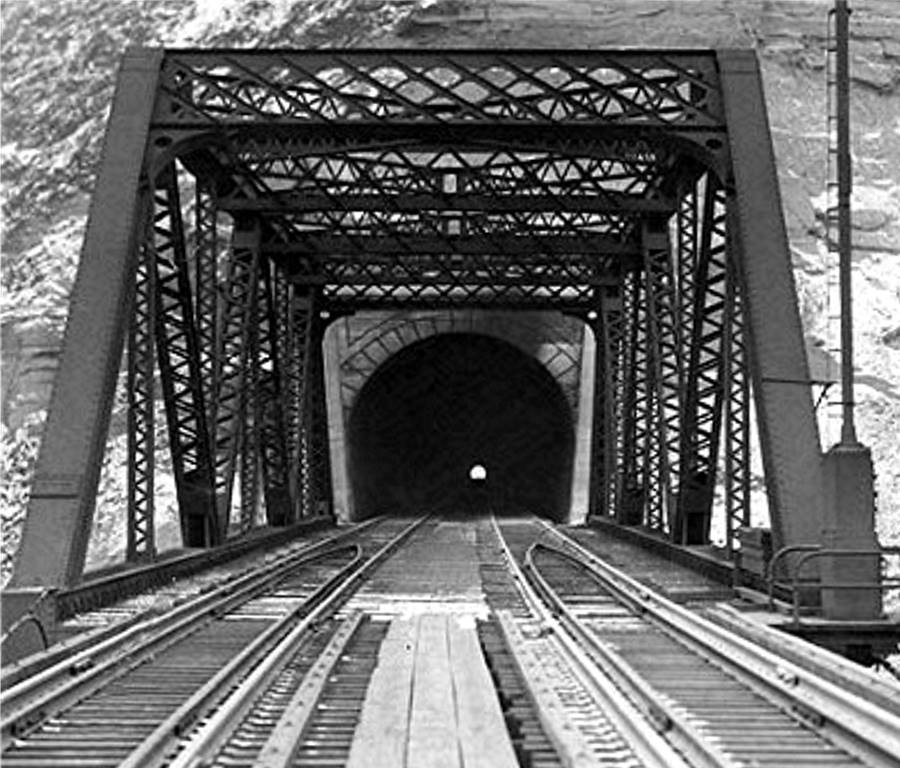

The one-mile Greentree Tunnel connects

the Rook Yard with the old West Side Belt line along Saw Mill Run.

Photos Of The

Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad In Castle Shannon

Wheeling and Lake Erie trains pass over

the Castle Shannon Viaduct at Castle Shannon Boulevard.

Wheeling and Lake Erie Railroad trains

passing through Castle Shannon.

* Pictures and Video

of W&LERR trains in Brookline provided by Steven Mincin *

Life After the Railroad

For the Wabash

Tunnel and Bridge Piers

Although the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal

Railway ceased operation in 1908, it's legacy has endured. Over a century later,

the Wabash Tunnels and the Wabash Bridge piers keep coming up in plans for new

Pittsburgh transportation ideas, becoming what many Pittsburghers consider

a huge money pit. That's a lesson George Gould learned over one hundred

years ago.

The Wabash bridge leads into the Wabash Tunnel,

exiting on the south end along Woodruff Street.

The neglected and unused Wabash Tunnels became a lure for other doomed transportation projects. Passenger rail

service through the tunnel continued until 1931. That same year, Allegheny County

bought the tunnel for $3,000,000 with the intention of converting it to an automobile

traffic tunnel to relieve some of the growing congestion at the Liberty

Tubes.

A $5000 feasibility study was commissioned

in 1933 to determine whether the tunnel was suitable for automobiles. Old stories

say that railroaders had to lay low when passing through the unventilated tunnel.

The problem of ventilation and the cost of addressing the issue were enough to scrap

that project. While the county deliberated, limited freight rail service continued

through the tunnel until 1946, when the Wabash Terminal in downtown Pittsburgh was

destroyed by fire.

The condition of the South Portal of the Wabash

Tunnel along Woodruff Street, circa 1963.

Skybus - The Westinghouse

Transit Expressway

The tunnel remained dormant from 1946

until 1970, when the Port Authority purchased the property. A year later the transit

authority began a $6 million project to ready the tunnel for the Westinghouse

Transit Expressway, or "Skybus," a revolutionary yet controversial rubber-tired

automated people mover system. A demonstration project of the Skybus system was built in South Park. If successful,

a bridge would have been built across the Monongehela using the original Wabash

Bridge piers to bring the system into downtown Pittsburgh. In the end, high costs

and politics doomed the project here in Pittsburgh.

Between 1994 and 1997, an additional

$8 million in renovations were made to the tunnel by the Port Authority, this

time in conjunction with plans for a major busway to serve the western

suburbs and the Greater Pittsburgh Airport. As with Skybus, this project

envisions the construction of a new bridge across the Monongahela River,

possibly using the old piers from the Wabash bridge.

The Airport Busway

In 1996, a $3.1 million contract was

awarded to demolish the Skybus runway system and install new paving and drainage

inside the Wabash Tunnels. In 1998, a new portal building was constructed at the

west end of the tunnel and the existing portal building on the city side,

visible from downtown on the face of Mount Washington, was rebuilt. Ventilation,

electrical and communication services were also updated.

By the end of the 20th century, with

millions of dollars of renovations again performed in anticipation of the

tunnel's rebirth, no final decisions had been made on the new Airport Busway

project. Ideas were still being submitted, debated and challenged in court.

Only one thing seemed certain, and that was that as long as the Wabash Tunnels occupied a space in the Pittsburgh landscape, it would draw the

attention of those with grand schemes and grand dreams. It had become one of

Pittsburgh's biggest money pits.

The Wabash Tunnel north portal in 1999.

Finally

... The Rebirth of the Wabash Tunnel

In 2000, plans to link

the Wabash Tunnels to the new Port Authority's $275 million West Busway were dropped.

The Money Pit had claimed another victim. All of the tax dollars spent on

planning and related construction had been wasted. As the Wabash waited

patiently for it's next victim, plans were introduced to open the tunnel

to vehicular traffic during rush hours as a HOV accessway into and out of

downtown Pittsburgh to relieve congestion at the Liberty and Fort Pitt

Tunnels.

In 2003, the Port Authority awarded

an $11 million bid to build ramps to link the tunnel to Carson Street across

from Station Square and to Route 51 at the southern end. As Pittsburghers

patiently awaited the inevitable bad news that the project would be somehow

abandoned, the unthinkable actually happened!

On December 26, 2004, nearly two years

after their 100th anniversary, and a mere 59 years since being permanently

mothballed by the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad, and a mere $31.1-plus

million or so taxpayer dollars later, the Wabash Tunnels was reborn as our city's

newest HOV (High Occupation Vehicle) accessway. The tunnel is a one-way road

that is reversed to accomodate the differing traffic flow patterns. As hard

as it was to imagine for Pittsburgh's old-timers, the tunnel was actually

open to vehicular traffic.

Ramp leading to the north portal

of the Wabash Tunnel.

It was a great day for the city of Pittsburgh,

but the cautious few had their doubts. Was the curse of the Wabash finally

laid to rest? Had the demonic curse that afflicted this hole in the Mount

for the past 100 years been finally been excorcised? Only time could tell.

The city kept its' fingers crossed and hoped for the best.

* Graffic courtesy of the Post-Gazette

*

The Saga Continues ...

In January of 2007, only two

short years since the opening of the tunnel that was to revitalize traffic flow

in and out of the city. Pittsburgher's are once again shaking their heads in

disbelief as the mounting cost of operating the century-old money pit is starting

to take a toll on Port Authority and municipal coffers.

Forecast to handle

approximately 4500 vehicles per day, daily traffic flow in April of 2005 was

closer to 150 vehicles per day. It was estimated that the tunnel was costing

taxpayers $12 for each vehicle that passed through. The Port Authority, already

struggling with budgetary problems from its regular transit operations, is

paying nearly $600,000 per year to a private firm to maintain the facility.

If the Port Authority closes the tunnel, then the agency will be forced to repay

$20,000,000 in federal grant money used to refurbish it in the first

place.

Read the following 2007

Post-Gazette articles for a look into the madness:

"Wabash Tunnel Has Become An Expensive

Venture"

"PAT faces tough decision on Wabash

Tunnel"

The entrance to the Wabash Ramp on

Carson Street.

A Bomb Shelter

Heads are spinning and confusion is

setting in. The brightest minds in Pittsburgh can't figure this one out.

Maybe the guy who wanted to turn it into a cocktail lounge had the right

idea.

Another suggestion would be to sell it

to some eccentric millionaire who renovates it into a private home. There's

plenty of square feet to develop, there are two private driveways leading to

the front and rear entrance, the veranda on the city side will offer a

spectacular view, and the home can double as a bomb shelter in case of a

terrorist attack.

The North Portal of the Wabash Tunnel

in 2007.

Whatever the future holds in store for

the much-maligned Wabash Tunnels, nothing can take away the fact that this

prized piece of real estate has most definitely earned its' place in the

annals Pittsburgh city lore. |