|

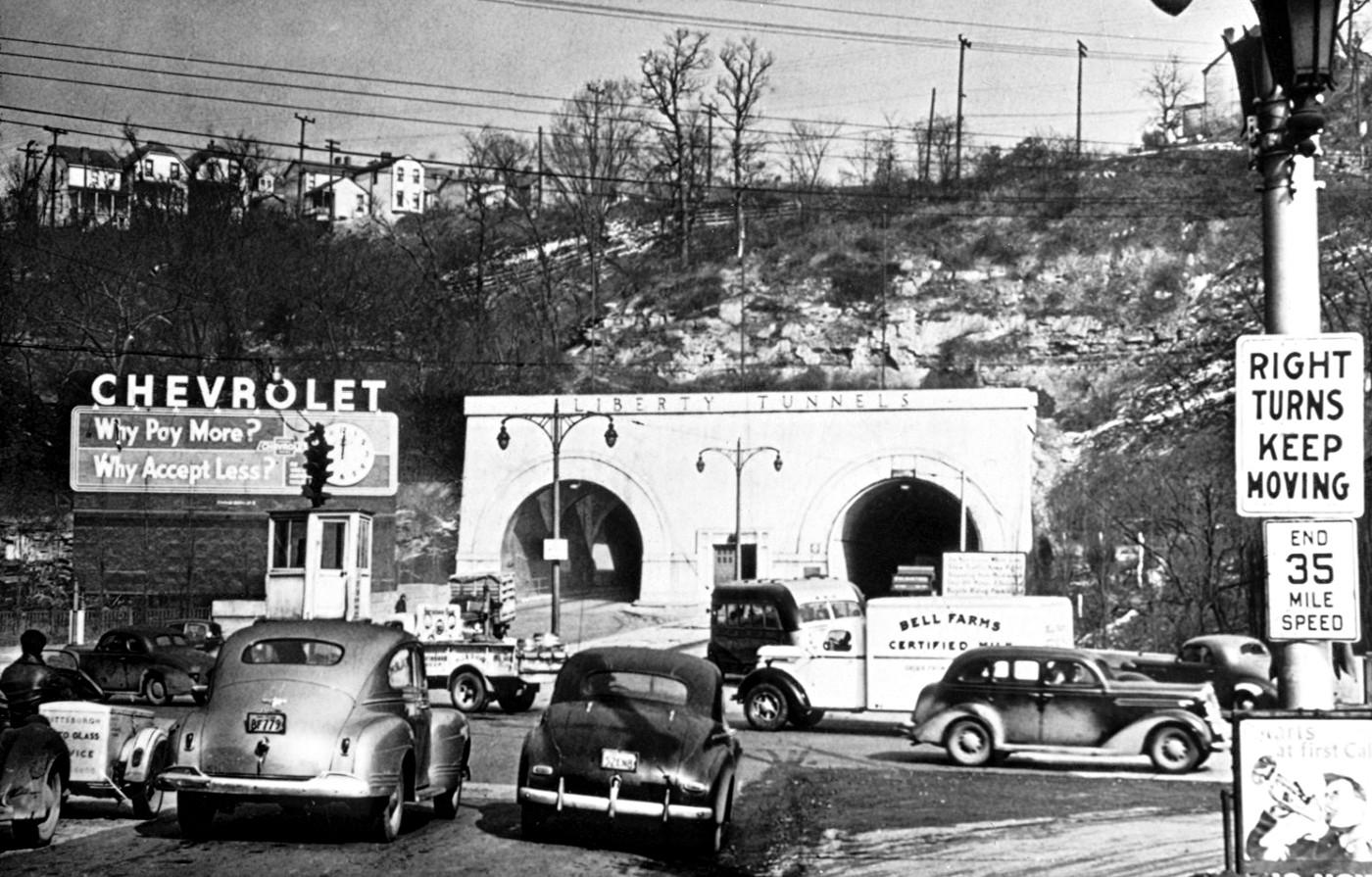

A 1924 postcard showing the Southern Portals

of the Liberty Tunnels along West Liberty Avenue.

History

of the Liberty Tunnels

1950s era postcard showing the northern

portals of the Liberty Tunnels.

Early South Hills

Transportation Difficulties

In the latter part of the 19th century,

the city of Pittsburgh was growing rapidly to the east, the north, and on the

South Side. However, the five-mile long, 400-foot geological obstacle known

as Mount Washington presented a major barrier to development in the South Hills

area.

With transportation mostly limited

to horse-drawn wagons and walking, residents of the South Hills had to rely

on a series of inclines to traverse the hill, or they took the long way to the

city, either up Warrington Avenue and down Arlington Avenue, or along the Saw

Mill Run Valley to the West End.

These difficulties slowed the process of

South Hills suburbanization, and the area retained a sparsely populated rural

flavor, consisting of mostly rolling hills and tracts of farmland.

In 1904, the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel was built to extend streetcar service to

the South Hills Junction and onwards to the southern boroughs. The new tunnel, the electric

railway and the advent of motorized transportation accelerated development in

West Liberty Borough (Brookline/Beechview) and other southern communities like

Dormont and Mount Lebanon.

As the population grew, so did the

amount of vehicular traffic. Soon it became necessary to find a quicker and

easier way to get traffic to and from downtown Pittsburgh.

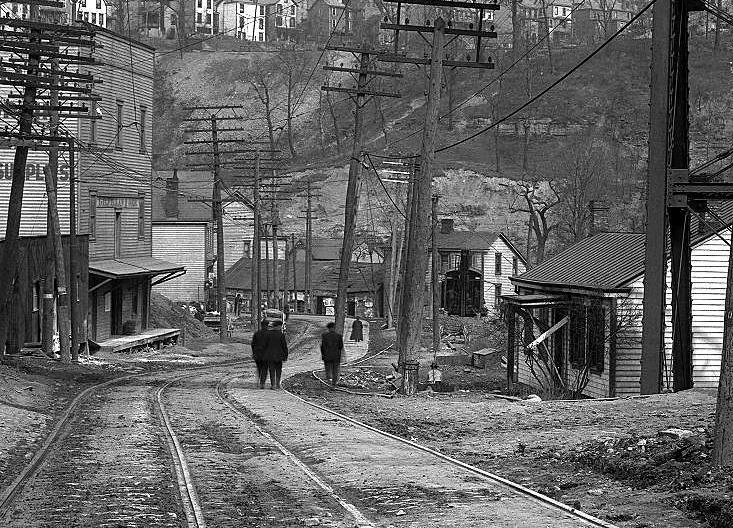

The South Hills Junction in 1906 (left) with

a billboard advertising home sales in Brookline, the 15-minute suburb,

and the Bell House Tavern in 1910, located on Warrington

Avenue near the intersection with West Liberty.

A Tunnel Is Proposed

In 1909 the South Hills Board of Trade

persuaded the Allegheny County Commissioners that a tunnel would be a boon to

the region. The added cost of shipping goods and building supplies over or

around Mount Washington was becoming a severe detriment to commercial prosperity and

land development.

Proponents estimated that the tunnel

would dramatically increase property valuation and act as a catalyst to real

estate development in the region. It was agreed that a new Mount Washington

tunnel, and a connecting bridge over the Monongahela River, were essential to

the growth of the city, but no plans were in place and no promises were made

by the commissioners as to when such a project would begin.

An 1888 picture showing the north face of

Mount Washington. After years of debate, the location for the northern

portals of the South Hills Tunnel would emerge in the center of the image,

behind the roof of the tall building.

While the overwhelming consensus throughout

the South Hills was that a tunnel was necessary, the location of the proposed tunnel

became a source of heated debate. Several different plans were introduced, each with

the southern and northern tunnel portals emerging in different locations.

Acceptance of the individual proposals had

much to do with where one lived and the benefits to that particular community,

with the overall benefit to the city overlooked.

The first proposal to receive widespread

support was the Shingiss-Haberman plan, or the "high" tunnel. The southern portal

would have been at Haberman Avenue and Warrington Avenue, up the hill from the South

Hills Junction. The northern portal would have been on Mount Washington, above Arlington

Avenue and East Carson Street.

A double deck bridge over the Monongahela River

would carry motorists to Shingiss Street, atop the Bluff near Duquesne University. This

proposal placed the northern portals eighty feet higher and the southern portals 184

feet higher than the present-day tubes. It offered the greatest benefit to the

communities of Mount Washington, Allentown, Knoxville and Beltzhoover.

1919 map showing the various proposals for the

location of the Liberty Tunnels. #1 is the Haberman, or "high"

tunnel. #2 is a proposed extension. #3 is the Morse plan, running parallel to

the abandoned Neeld Tunnel,

#4 is a cut proposed by City Engineers, #5 and #6 were the Shalerville proposals.

The seventh

alternative, the Bell Tavern or "low" tunnel, was adopted by the County

Commissioners.

As time progressed, other proposals were

put forth. One confederation of residents pushed for the tunnel to be built closer

to the line of the present-day Fort Pitt Tunnels. This was called the Shalerville proposal, and

was economically favorable to residents of Carnegie, Banksville, Bridgeville, Robinson

and Crafton.

Another alternative was submitted in 1914 by

City Engineer W. M. Donley, who proposed a deep cut through Mount Washington,

eliminating the need for a tunnel altogether.

The "High" Tunnel Or The "Low"

Tunnel

The South Hills Tunnel Association, comprised

of residents from Brookline, Beechview, Fairhaven, Dormont, Baldwin and Mount Lebanon,

wanted a tunnel that followed a low line and exited at Saw Mill Run near West Liberty Avenue. This

was called the Bell Tavern plan, or the "low" tunnel. It was so named

because of the proximity of the Bell House Tavern to the southern portal location.

The low tunnel proposal would allow access

to the Saw Mill Run valley

and the valley that extended southwestward to Dormont and Mount Lebanon, and had

the support of the State Highway Commissioner, Edward M. Bigelow.

Mensinger's Stone Quarry was located along

the hillside near the junction of West Liberty Avenue and Warrington.

Shown to the left in 1913, this spot would be, in 1919, chosen as the location of

the southern portals of the

South Hills tunnel. To the right is a 1915 view looking north along West Liberty

towards the hillside.

The low tunnel proposal had the southern portals

in there present-day location, and the northern portals positioned at East Carson Street

and South First Street, and had no accomodations for a direct link to a Monongahela River

bridge.

While South Hills residents and city planners

debated on which tunnel proposal was best, the county itself began construction of a

tunnel in the fall of 1915. Called the Neeld Tunnel, the plan was to run from East Carson and South Third streets to a southern

portal sixty-seven feet below Warrington Avenue near Boggs Avenue.

Work began on the Neeld Tunnel in July of 1915.

Located just below Warrington Avenue, it was the first

attempt at building a vehicular tunnel connecting the South Hills area and downtown

Pittsburgh.

Shortly after construction began, opponents

filed a lawsuit which challenged the county's authority to build tunnels. The

Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled against the county and work was halted.

"The Saga Of Pittsburgh's Liberty Tubes"

Geographical Partisanship On The Urban Fringe

An Article on the Tunnel Debates - by Steven Hoffman

"Liberty Tunnels Site Chosen After Exhaustive Research"

The Gazette Times - May 24, 1919

Eventually, after years of debate, in May 1919,

the low tunnel proposal was adopted, with one change. The Allegheny County Commissioners

ruled that the northern portal would be higher on the face of Mount Washington. It would

link up with a proposed new bridge across the Monongahela River.

This solution would eliminate interference with

existing traffic congestion on the busy East Carson Street. With the recent victory of

World War I in mind, both the tunnels and the bridge would carry the same name,

"Liberty."

The intersection of West Liberty Avenue and

Warrington Avenue in 1918 before the Liberty Tunnels.

Ground-breaking For The Liberty

Tunnels

Ground-breaking for the new tunnels was held on

December 20, 1919. The celebration took place on the Southern end of the project,

followed by victory dinner held at the Fort Pitt Hotel. Several dignitaries, including

the Governor of Pennsylvania, were in attendance.

The Pittsburgh Press reported that "an immense

crowd was present when County Commissioner Gumbert applied the electric spark that

exploded a light charge of dynamite on the hillside through which the tunnel will be

bored. A few minutes earlier the county commissioners, Gumbert, Harris and Myer and

Controller Moore, had been presented with silver plated picks and shovels by George

Flinn, of the firm that will build the tunnel."

"The entire ceremony was informal. The Almas

Club of Dormont marched to the scene of the ground-breaking, the parade being

augmented by delegations from Castle Shannon, Beechview, Brookline, Mount Lebanon,

Fairhaven and Brookside," the Press reported. The estimated cost of the tunnels was

$4,500,000. The contractor was Booth & Flinn, Ltd., the same firm that built the Mount

Washington Transit Tunnel in 1904.

The Tunnel Bore

The second construction milestone in the

life of the Liberty Tubes occured on April 9, 1920, when the boring process began.

The operation was witnessed by a crowd of 100 persons, including county and city

officials.

County Commissioner Addison C. Gumbert exploded

the first charge. Fragments of rock were hurled in the direction of the crowd, which

stood some 350 feet from the blast. Small chips of stone struck a couple of the

onlookers, but no one was injured. Two succeeding charges were detonated by Gumbert

and County Controller John P. Moore. The three explosions dislodged approximately

ten tons or rock.

The first official charge of dynamite in the

actual boring of the tubes was detonated on April 9, 1920.

Construction work was halted in late-1920 due to

an economic recession, then restarted in 1921. The revamped state of the economy actually

saved the county a considerable sum on the original cost assessment. Work proceeded quickly,

with the debris from the tunnel bores used in the creation of McKinley Park on Bausman

Avenue.

Shaking Things Up

Throughout the daily, and nightly, tunnel boring

process, there was considerable discomfort to local residents living near the construction

zone, as reported in the Pittsburgh Daily Post on October 31, 1920 article

entitled:

"Broken Dishes, Spoiled Cakes, Disturbed Sleep

Only Few of Troubles of Housewives Living Near Mouth of New Tunnel;

Blasting Cause".

"Their dishes are being broken suddenly and

regularly; babies are awakened from their afternoon nap at the most inconvenient times;

cakes in the process of baking are rendered soggy and unedible. Those are a few of the

things that are said to be happening," the article stated.

"It's the blasting in the tunnel. Those mighty

blasts, which are going off every hour or so, throughout the day, are shaking things up

considerably in the neighborhood."

The housewives formally registered their complaints

with the county commissioners, but since the tunnel could not be built without blasting,

there was little that the commissioners or the contractor could do to remedy the

situation.

A working platform inside the tunnel for shoring

up the sidewalls and ceiling. The rail cars were used to haul material.

Friendly Competition

Once work began in earnest, progress came quickly.

Each tube is a separate bore (east and west), and they were drilled simultaneously from

both the north and south ends, twenty-six feet apart. The crews for both the east and

west bores worked in two 12-hour shifts, with each shift averaging ten feet per day. This

was a stunning pace, no doubt encouraged by both pay incentives and friendly

competition.

Crewmen were payed eleven hours for nine linear

feet in a day and twelve hours for ten, no matter how long it took. Crews worked hard to

finish their day in good time. Also, above the entrance to each bore was a flag pole. There

were two flags, one an American flag and one a black flag. Whichever shift finished the day

first got to hang the American flag above their bore.

Streetcars Not Welcome

From the time the first stick of dynamite

went off to build the Twin Tunnels, the Pittsburgh Railways Company began lobbying

the County Commissioners for pass-through rights. Eager to relieve congestion at their

South Hills Junction Complex, the transit firm wanted their streetcars to operate in

the tunnels.

In January 1922 it looked like two of the

three commissioners favored this option.

"They will have to show me that it will

not be a good thing to run trolley cars through the Liberty Tunnel," said

Chairman Gumbert. "It is a traffic tunnel, built for all kinds of traffic, and

traffic of course includes street cars."

Engineer A. D. Neeld, on the other hand,

citing future traffic projections declared that "the tunnel should be confined

to foot and vehicular traffic and trolley cars should be barred."

The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported on February

24 that the people of Dormont, Mount Lebanon and Brookline, whose routes would be

affected, had no interest in having streetcars in the tunnel. Burgess William Best

presented the commissioners with a Dormont Council resolution opposing the

proposal.

Politicians are much maligned and often

for good reason. But sometimes they have great foresight. In what proved to be

one of the smartest acts ever recorded on the public record, on March 6, 1922, the

County Commissioners passed a resolution stating that "there shall be no street

car franchises granted for use in the Liberty Tubes."

The Two Ends Meet

The boring of the 5889 foot tubes was

completed on May 11, 1922 at 10:15am when County Commissioner James Houlahen

closed the switch that exploded a charge of dynamite that blew away the final

rock and earth that seperated the north and south bore of the western (outbound).

tube.

Approximately 300 representatives of the

county and city governments, civic organizations and others witnessed the ceremony.

The party entered from the north end to a point about 500 feet from the portal

opening, where a switch was mounted. When the switch was thrown a terrific

explosion rent through the air, followed by a shower of rocks and debris. As the

smoke cleared, streaks of daylight filtered through.

Top - City and county officials at the northern

entrance of the Liberty Tunnel awaiting the final blast

which opened the west tube. Bottom - Officials on arrival at the southern

entrance of the tunnel.

The crowd climbed over rocks and construction

materials to the center of the tube where platforms had been erected. Short

addresses were made by Commissioner Houlahen, President Daniel Winters of city

council, former County Commissioner Gilbert Myer and others.

A. D. Neeld, consulting engineer on the

tunnel project, informed the crowd that the two ends of the eastern (inbound) tube

were only 1,500 feet apart at that time, and it was expected to be opened within

the next ninety days.

Showing the hole made by the last blast seperating

south and north openings of the west tube on March 11, 1922.

L to R: R.L. Lee, A.D. Neeld, James Houlahen, J.B. Snow, George H.

Flinn and M.L. Quinn.

The Best Rock Tunnel

Tunnel engineers received a glowing review

on their achievements to date when, on April 8, 1922, Clifford M. Holland, the chief

engineer in charge of the New York-New Jersey tubes, and Robert Ridgeway, chief

engineer of the traffic commission of New York, visited Pittsburgh to inspect

the progress of the bore. They declared the design and construction to be the

finest they had ever seen.

"Pittsburgh people have cause to congratulate

themselves on this work," said Mr. Holland. "It is the best rock tunnel I have

ever seen. I saw not a flaw in the work today, and the progress on construction is a

world's record. I never before saw a tunnel driven where the excavation was in a

complete section, as is this work. Usually a section is excavated at the top, then

a second slice taken off, and sometimes the work progresses in three

benches."

Ridgeway was also enthusiastic. "I

look for flaws," he said, "but I confess I found none."

Boring proceeds on the Liberty Tunnels in 1921,

as seen from the South Portal entrance along West Liberty Avenue.

Note the flag poles above each tunnel entrance. The American Flag flutters

over the east bore, indicating

that the men working the prior shift had finished their daily quota before those

in the west bore.

"Structural Design And Ventilation Of Liberty

Tunnels"

Engineering News-Record - Volume 85 -

July 8, 1920

"Boring Liberty Tunnels At Pittsburgh"

Earth Mover - Volume 8 - March 1921

"Liberty Tunnels Construction, Pittsburgh"

Public Works - Volume 51 - July 23, 1921

Now the work of finishing the walls and

installing the tunnel infrastructure began. It would take another year of

back-breaking work before, in August of 1923, the paving of the concrete road

surface was underway and the project nearing completion.

The Southern Portals in August 1923 during

the paving of the road surface.

Public Inspection

On September 8, the new tunnels were thrown

open for public inspection. More than 100 persons took advantage of the opening to

marvel at the twin tubes. County Commissioner Gumbert announced to the crowd that

the tunnels would not be officially opened to traffic until March or April, pending

the installation of the ventilating, lighting and cement facing, those items not

yet finished.

At the time of the inspection, the tunnels

were already well lighted and most of the cement work was dry. Those who made the

tour went in the east tunnel and came back the west tube. A little dog that dashed

into the east tunnel was the first to go through. Several boys followed the dog,

running through the tunnel and back again.

Dignitaries and local residents gathered on

September 8, 1923 to inspect the Liberty Tunnels.

Unheeded Warnings

By New Years Day 1924, preparations for

the grand opening of Pittsburgh's newest marvel were nearing completion. The

only item not in service was the ventilation system, a component that had been

held up due to unforeseen circumstances. The Pittsburgh Press reported on

January 13 that preliminary air quality trials were performed with up to 200

cars sent through the tunnel without ventilation.

A. C. Fieldner, head of the United States

Bureau of mines declared the result of the tests would determine whether the

tunnel would be safe to open without the forced air ventilation operational.

After the procession of vehicles had driven in one tube and out the other three

times, the entrances were sealed and samples of air taken.

A.C. Fieldner of the Bureau of Mines (left),

holding one of the canaries used in the testing,

while W .P. Yost and Dr. W. J. McConnell does a blood test on G. W.

Jones.

Both tunnels were murky with the

stagnant vehicle exhaust. Mr. Fieldner asserted a rough test that showed a

strong presence of poison gas. He expressed the opinion that it would not be

safe to linger in such a charged atmosphere for two hours and that it might

not be safe to drive as few as 200 cars through before allowing the

atmosphere to clear.

Cages containing canaries were distributed

through the tunnels, and although the birds were not overcome, Mr. Fieldner said

carbon monoxide might be discharged in such quantities that it would not be worth

the expenditure in time and money to open the tubes until the ventilating system

was functional.

The Grand Opening Of The

Twin Tubes

In December 1923, the tunnels themselves

had been completed for well over a month, but the opening delayed while work

progressed on the air flow issues. Public sentiment favored opening the tube to

traffic immediately. Even engineer Clifford Holland chimed in, expressing shock

at the delay in opening the tunnels.

With months remaining before the ventilation

system would be operational, the County gave in to the increasing pressure and,

despite all warnings, opened the Liberty Tunnels for the first time to all-day

traffic on January 30, 1924.

The decision was greeted with enthusiastic

fanfare by the public. Strictly enforced speed restrictions were placed on motorists

in an effort to keep the toxic fumes to a minimum and air quality tests were done

hourly.

A Freehold Real Estate advertisement

from 1924.

Considered an engineering marvel, in 1924

the twin tubes were the longest automobile tunnels in the world, holding that

distinction until the opening of New York's Holland Tunnel in 1927. In addition to

motorized transportation, horse-drawn wagons were permitted to use the tunnels

(a practice that continued until 1933), and a well-trodden pedestrian walkway was

present in each tube.

The total cost of the project was $5,994,642.83

to be exact, which was approximately $1.5 million over the original estimate. Despite

the added cost, the economic benefit to the city, county and the entire South Hills

would more than make up for the expense.

Because of the Twin Tubes, real estate sales

and housing development in the southern communities entered another boom phase.

The population of Brookline, Dormont and Beechview more than doubled as a result.

Mount Lebanon saw a 500% population increase! Three farms in Brookline that were

appraised at $68,000 in 1920 saw their property valuation increase to $1.3

million.

Carbon Monoxide Crisis

For nearly four months the tunnels

functioned, with a measure of good luck, according to plan while officials

waited eagerly for the stalled installation of the ventilation

system.

Unfortunately, while jurisdictional

strikes and other issues delayed implementation of the vital forced air flow,

that luck ran out. On a sunny morning in May, the proper combination of

events led to the crisis that Dr. Fieldner from the Bureau of Mines had

warned of.

The north tunnel entrance after all motorists

had been rescued. The large picture on the left is C. H. Hooker of

the police force who bravery was outstanding. Patrolman Thomas Morrison, the

large picture on the right,

also distinguished himself. A view of the streetcar tunnel, which was opened

to the public for

pedestrian traffic, including the gentleman on the far left. The picture at right

center is Motorcycle Patrolman Louis Keebler, after being resusitated.

On May 10, 1924, there was a

mass-transit strike that idled the Pittsburgh Railways streetcar service.

Thousands of commuters who normally took the trolley to work turned to

their automobiles to make the commute, resulting in bumper-to-bumper traffic

jams all around the city.

During the morning rush hour, cars backed

up inside the tubes from one end to the other, and soon traffic came to a halt.

While vehicles idled inside the tunnels, many motorists helplessly began to

succumb to the dangerous buildup of carbon monoxide gas and literally passed out

at the wheel of their cars.

The quick reaction of the city police

and firemen prevented any fatalities, but several people were overcome with

fumes, treated and taken to the hospital. The crisis was real and the results

caused an immediate and overwhelming urgency in ventilating the tubes by the

quickest means available. Differences were put aside and contractors got to

work right away on a solution.

"Courage, Cool Courage, Looms Large As Day's

Crisis Reveals Unsung Heroes"

Pittsburgh Press - May 10, 1924

The Ventilation System

Until a solution could be found, the city

began counting vehicles and tunnel use was restricted. The lack of a proper

ventilation system was an unheeded concern, one that should have been averted

except for labor difficulties and the unexpected presence of abandoned mine

workings deep underground that required special considerations.

On April 23, 1923, work was progressing nicely

with the ventilation system. The picture on the left shows the

eastern shaft which was nearing completion. The other shows two workmen entering the

shaft vias a bucket.

Work had begun in early 1923 on drilling

the ventilation shafts from points atop Mount Washington directly above each tube.

Work was progressing nicely in April 1923, but was soon halted when the undocumented

mines were encountered 150 feet below the surface.

Engineers worked with the U.S Bureau of

Mines to overcome those difficulties, but the solution took time to create and

implement. When completed the ventilation system consisted of two pairs of specially

designed concrete and steel reinforced 192-foot vertical shafts.

Ventilation intake and exhaust shafts were

installed near the center of each tube.

The dual shafts continuously pumped fresh air

into the center of the tunnels while simultaneously pumping air out from a mechanical

plant located on Mount Washington, creating a directional air flow in each tube.

Each of the massive fan units consists of a multi-blade wheel 115 inches in diameter

by 54 inches long. Electric power was provided by two 11,000 volt supply

lines.

Progress as of December 11, 1923 on the building

that would house the ventilation system and control center.

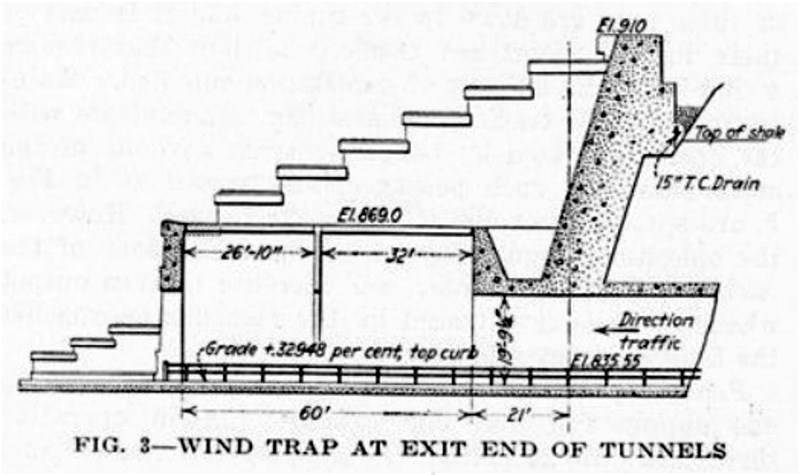

The air flowed with the direction of

traffic. At the exit of each tube, a pergola-like windbreak above the portal

prevents cross-currents of outside air from obstructing the air flow leaving

the tunnel. The ventilation shafts were operational by August, and after a

month's trial period, on September 1, 1924, traffic restrictions were

eliminated.

Ventilation for the LibertyTunnels is provided

by this power plant, located atop Mount Washington along Secane

Avenue. The plant, opened in 1924, can push 1,100,000 cubic feet of air per minute

through the tunnels.

"Exhaust-And-Supply Ventilation Of A Long Street

Tunnel"

Engineering News-Record - Volume 94 -

1925

Tunnel Walkers

Pittsburgh's revolutionary tunnel ventilation

system worked fine for automobile traffic and the occupant's of those vehicles who,

for the most part, were not confined inside the tunnels for long periods of time.

It did not, however, have the same positive effect for pedestrians walking the entire

length of the dark, dank tunnel.

On October 17, 1926, Miss Aileen McLaughlin,

aged 17, of 2815 Kenilworth Avenue in Brookline, was overcome by carbon monoxide

fumes while walking through the southbound Liberty tube and collapsed on the

walkway.

Passing motorist W.C. Burkin, of 6618 Bethel

Place, saw her fall and stopped his vehicle. Burkin helped Miss McLaughlin into his

vehicle and transported her to Mercy Hospital, where she recovered after a short

stay in the emergency room.

Policemen on duty at the tunnel, when asked

about tunnel-walkers, said that approximately fifty people walk through the tunnels

on a daily basis. For these people, the risk of carbon monoxide exposure was a real

concern, but luckily there were only a few incidents like Miss McLaughlin over the

years.

The northern end of the tubes in 1925.

Bridge work was beginning and soon McArdle Roadway construction would start.

When the intersection was completed in 1928, a traffic circle

was installed to facilitate the four-way flow of traffic.

Imagine the effort Miss Aileen McLaughlin made along Carson Street and Brownsville

Road just to get to this point.

Now she must walk the 1.12 miles through the tunnel to West Liberty Avenue,

through the heat and fumes.

This might have been a daily thing for the young lady, trudging home through

the dungeon.

Constant Monitoring

High atop Mount Washington, in the ventilation

building, was a finely tuned instrument that kept a constant check on the amount of

carbon monoxide in the Liberty Tunnels. The device was a carbon monoxide recorder

that calibrated minutely the amount of the deadly, odorless, colorless and tasteless

gas in the tubes.

It was wired to an alarm system which flashed

on a yellow light and sounded a buzzer when the fumes became even the slightest bit

heavy. A red light signalled when the amount of gas reached a critical level. The

ultra-sensitive equipment was kept in an air-tight glass cage.

Most of the time, the reading was around one

unit in 10,000 units of air. At 3:15pm on November 23, 1935, the gas had reached

1.63 units. Two hours later, when the evening peak traffic was on, it had jumped to

six units and the buzzer was sounding. This lasted less than five minutes, as the

equipment monitor also controlled the amount of airflow being pumped from the

ventilation building down into the tubes.

Thomas W. Moran monitors the carbon monoxide

detection equipment, the mainspring of the ventilation system in the

Liberty Tunnels. The graph to the right shows the varying amount of the deadly

gas present in the each tube.

Six units of monoxide can make a person

nauseous. Ten parts can make a person sick to the stomach. Twenty will make someone

very sick. A couple breaths of 200 units in 10,000 is all it takes to

kill.

The July 24, 1953, Pittsburgh Press ran an

article reporting that during rush hour the readings were a bit over five parts

per 10,000, which were hazardous and causing concern. Also discussed was the

cumulative effect of the carbon monoxide fumes on the traffic cops that stood

at the exit and entrance for hours at a time. It was agreed that the officers

were in harms way, not only from the onrushing traffic, but from the air they

breathed.

Smoke Emergencies

As if vehicle exhaust did not create

enough smoke, on June 15, 1967, the Pittsburgh Press reported on a fire outside

the ventilation building that burned through the double doors and sent a long

stream of murky smoke through the fresh air vents down into the southbound tube.

The situation was brought under control within a short time, but it took some

time to clear the tunnel of the thick, dark smoke.

Then, ten days later, memories of the

May 1924 carbon monoxide crisis were revisited when a three-car accident stalled

500 cars, trucks and buses in the southbound tube. During the 45-minute delay,

a number of motorists became sick from exhaust fumes.

Two county policemen attending the accident

were also overwhelmed. The officers, Andrew Hungerman and Daniel Brady, and others

who had taken ill were sent to Mercy Hospital. A detector malfunction was blamed

for the failure of the ventilation system to disperse the smoke. Partial blame was

also placed on motorists who left their vehicles running during the lengthy

delay.

Despite ongoing efforts over the years

to remedy the problem with the toxic fumes, the problem has never really solved.

As the amount of thru-traffic continues to increase, new calls go out every few

years to address the issue. This pattern has persisted to this day.

Ambulance Escorts

If an ambulance was headed towards the

tunnels from either north or south, a call would go into the police office in

the tunnel and the officers would spring into action. One would barricade the

left lane in either the east or west tunnel and a motorcycle officer would

stand ready to provide an escort through the tunnel and on to the destination

hospital.

Officer R.L. Carr waits for an incoming

ambulance while Officer Joe Sarachman mans a barricade on August 16, 1952.

A Dangerous Intersection

Another problem that became evident just a

short time after the original opening of the Liberty Tunnels was the increasing

traffic congestion at the intersection of Saw Mill Run and West Liberty Avenues.

The resulting number of accidents involving vehicles and pedestrians was

alarming.

Vehicles pass at the South Portals of the

Liberty Tunnels (left) in 1932, before the installation of traffic signals.

The sign on the tunnel reads "R - U - A Safe Driver?" To the right is a view

of the North Portals,

in November 1932, with a similar sign posted that reads "We're Here For

Safety."

The traffic circle outside the North Portals was condensed in 1933

and then it was finally removed altogether in the 1940s.

In 1930, the busy crossroads was identified

in a Pittsburgh Press feature documentary as one of the city's ten deadliest traffic locations. By 1932 there were 25,000 vehicles using the tunnels each day, already

exceeding the designed capacity. By the end of the 20th century that number had

more than tripled, to nearly 80,000.

Traffic management was also a big issue

that needed to be addressed. At the time, there were no traffic signals at

either end of the tunnels. Furthermore, the traffic pattern inside the tunnels

themselves was a nightmare, exacerbating the conditions outside. In the dimly

lit tubes, vehicles could change lanes at will, large trucks could drive in the

center, and horse-drawn wagons were still allowed to pass through.

The traffic circle at the tunnel entrance

was condensed in 1933 and removed altogether in the 1940s.

Compounding the issue on the northern end

of the tunnels was the traffic circle at the intersection of the tunnel portals

and Mount Washington (McArdle) Roadway. By 1930 the circle had become a serious

impediment to the traffic flow and a serious safety issue.

Finally, in 1933, the circle was condensed

to a point that tunnel traffic had a straight approach onto the bridge and county

policeman were positioned at the crossroads to direct traffic. In time, traffic

lights were installed outside the portals. The circle and "Liberty" monument were

removed altogether in the 1940s.

This traffic signal (left) was installed at

the southern end of the tunnels as an experiment on September 1, 1937.

The light was made permanent shortly after, and later a small shed was built

to house a traffic officer.

This is the shed on December 2, 1941, after it was knocked over by an errant

motorist.

Another improvement was adding two

additional lanes, for the left turn onto Saw Mill Run Boulevard, at the south

plaza. Change came slowly, and it was until the late-1930s that most of

these problems properly addressed, and even then, driving conditions both

inside the dark, hazy tunnels and outside at the often congested southern and

northern intersections remained a problem for years to come.

A view to the south from atop the South

Portals on May 16, 1954. The "No Left Turn" notation was a

reminder that left turns into the tunnels from Saw Mill Run Boulevard

were now prohibited.

Despite two-plus decades worth of efforts

at correcting the status of the southern intersection, the March 19, 1956,

Pittsburgh Press identified the Saw Mill Run/West Liberty intersection as the

#1 most dangerous intersection (out of a field of forty-seven), with a total of

ninety-nine accidents in 1955.

War Rationing Brings Other

Challenges

Flat tires were also a concern inside the

tunnels, especially during World War II when rubber was a military necessity and

new tires were not available. The stalled vehicles caused traffic to back up and

the vehicles themselves were difficult to remove. Motorists often had to drive

out of the tube on the flattened tire, with the metal rim tearing the tire to

shreds.

Property and Supplies Director Harry

Aufderheide and Police Sergeant Ernest Andrew

are shown testing one of the new "jack on wheels" on August 26,

1943.

In 1943, an average of three vehicles a

day were getting flat tires while driving through the tubes. To assist with that

problem, the county purchased three "jacks on wheels," metal cradles with wheels.

A flat tire was lowered into the cradle and the owner could then drive out of the

tunnel without doing further damage to the tire.

1940s-era long view showing the lower end

of West Liberty Avenue,

including the trolley ramp and the Liberty Tunnels.

Liberty Tubes - A Toll

Tunnel?

On July 7, 1934 an article ran in the

Pittsburgh Press discussing the pros and cons of Allegheny County charging a

toll (five cents) for South Hills motorists to use the Liberty Tunnels. The

purpose of this toll was to pay for the many road projects scheduled to occur

in the Pittsburgh and the South Hills. Saw Mill Run Boulevard had recently been completed and there were

projects proposed to build the West End Bypass and the Fort Duquesne Tunnel and Bridge, connecting the Banksville Traffic Circle with

downtown Pittsburgh.

The debate lasted for two years, and

caused quite a political divide among city and county officials, not to mention

concerned residents of the South Hills. Many feared that this toll would isolate

the area, and force motorists to bypass the tunnel altogether for alternate paths

over Mount Washington, further increasing traffic congestion.

Another objection was that this would set

a precedent, allowing the imposing tolls on other bridges in and out of downtown

to raise funds. This in turn would isolate downtown itself and cause an economic

decline in the heart of Pittsburgh.

Meetings called by the Brookline Board of

Trade in late-1933 and early-1934, held at Brookline School, brought concerned

citizens from the South Hills together to protest the plan. Similar meetings were

held in Dormont, Overbrook, Beechview and Mount Lebanon. South Hills residents

drafted several resolutions to city and county officials condemning the

proposal.

Concerned citizens gather at Hillsdale School

in Dormont to protest the county's toll proposal. The residents formed

an organization to fight the tolls at "any cost." The group

even drafted correspondence to President Roosevelt.

Although the County Commissioners were

in favor of the project and ready to begin putting the plan into effect, and City

Council voted to support the measure, Mayor John S. Herron vetoed their bill. The

council did not have enough votes to override. This development left the County

Commissioners in a bind.

When the county indicated that they were

prepared to install toll booths in the southern approach to the tunnels, the

city threatened to station police officers on site to allow motorists to pass

without paying the charge.

In July 1935, some interesting statistics

were presented regarding the effect of the Liberty Tunnels on the South Hills and

the associated increase in tax revenue collected by the county. In 1915, before the

tubes were built, the assessed valuation of property in Dormont was $4,269,610

compared to $17,241,820 in 1935. Valuations in Mount Lebanon went from $3,65,610 to

$28,456,400. Other communities had similar increases, meaning that the county has

already benefited substantially from the tunnels.

Finally, in November 1935, after further

political wrangling and intervention from the federal government opposing the plan,

the toll proposal was dropped, and funding for the continuing expansion of the road

network in the South Hills came from other sources, some of which would consist of

federal grants. It would be twenty-some years before motorists saw the completion of

the West End Bypass and the building of the new tunnel and bridge to downtown, by

then renamed the Fort Pitt Tunnel and the Fort Pitt

Bridge.

Here We Go Again

The toll debate was briefly revisited in

1978 when Councilwoman Michelle Madoff proposed a ten cent toll for all commuters

from the southern suburbs (non-city residents) using the Liberty Tunnels and Bridge

to enter downtown Pittsburgh. City residents would be issued a free pass. The

proceeds would be used for bridge and tunnel maintenance. The measure was soundly

defeated.

The Tunnel Jail

On March 23, 1975, the Pittsburgh Press

reported that back in March 1938, the County, which owned and operated the

tubes, installed a jail cell in the county police office at the northern

end. It was to "house any violators caught in the tubes, or escaping over

the Liberty Bridge, until a patrol wagon could be sent to cart them off to

jail."

Before that, county police had to leave

their post and take a prisoner to a police station or guard him in a closed

office. It is not known exactly how long the jail cell was in use, but it was

reportedly removed when the state took over the tubes in 1962.

Liberty Tunnels Improvements - 1938/1965

The tunnels received their first maintenance

improvements beginning on July 25, 1938. Repair work included paving, sewer overhaul,

fixing numerous cracks in the walls and ceiling, water-proofing and painting. New

sodium lights would be installed along with reflective porcelain tile along the walls

to increase illumination inside the dark tunnel.

Detours were posted for South Hills motorists

during the 1938 southbound tunnel closure.

The sodium lights were so bright that for the

first time since the opening of the tubes in 1924, the "Lights On" requirement was

removed. The thirteen month project was completed on August 28, 1939.

In another first for Pittsburgh and the

Liberty Tunnels, temporary antennas were installed in 1939 to provide AM radio

reception. Three aerials, all originating from the ventilator building on Mount

Washington and strung down the air shafts, were installed in each tube. One was

located along the ceiling and one along the top of each tile wall.

The inbound tube on January 4, 1940, brightly lit

with sodium lighting and white porcelain tile walls.

Radio reception inside the tunnel was

something radio engineers considered impossible due to the grounding of so many

tons of steel. However, with the cooperation of KDKA radio engineers, the

experiment was a success. County electrical engineers ironed out the kinks in

the system and gradually improved the quality of the reception.

Finally, in April 1941, intensifier

amplifiers were installed at the base of the aerials, where they emerged from

the air shafts. This increased and clarified reception to a degree where even

radio signals from a considerable distance away from Pittsburgh were picked up.

This was a relief for motorists caught inching along slowly during the long rush

hour traffic jams who relied on KDKA radio, or other station, for the latest

news.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

on June 6, 1965. The inbound tube was closed due a four-month

tunnel rehabilitation project. It would be a decade before

the tunnel got a proper facelift.

Another round of upgrades were performed

in 1965, three years after the state assumed responsibility for the tunnels.

Twenty-five years had passed since the last renovation, and much had changed.

The roadway was now rutted in from end-to-end, the lighting system was failing

and the overall condition of the tunnels was poor. It had become so dark inside

the tunnels that the "headlights on" requirement was back in force.

Former Pittsburgher Louis Primavera,

in town visiting from Brooklyn NY, had a gripe for the state. "During my stay

I had occasion to drive almost every day along Route 51 to the University of

Pittsburgh ... The gripe is about the Liberty Tunnels."

Primavera continued, "The State of

Pennsylvania should be ashamed to keep those vital tunnels in such miserable

conditions! Don't you people believe in light, air and a safe pavement? The

first day I drove through them I really thought there was something wrong with

the steering wheel of my car."

Originally slated to be a comprehensive

$8.5 million renovation, the project was scaled back considerably. An emergency

$1.6 million upgrade included road resurfacing, overhaul of the drainage, electrical,

lighting and ventilation systems, and limited structural repairs inside the aging

tubes.

In the fifty years following their dedication,

these were the only real maintenance projects and upgrades performed on the Liberty

Tunnels. By the early-1970s the tubes were basically the same as originally designed,

and in real need of comprehensive structural and cosmetic rehabilitation.

The Ever-Evolving View of Pittsburgh

Much ado is made of the spectacular visual

display of Pittsburgh when a motorist exits the Fort Pitt Tunnels and the majestic skyline of Pittsburgh and the beauty of the three rivers

instantly come into view.

The same can be said, just not on such a

monumental scale, for the view one gets when exiting the Liberty Tunnels. Over the

years, the optics have changed as the skyline has evolved, but the feeling of wonder

is always the same. Downtown Pittsburgh is a beautiful sight no matter what

entranceway one chooses.

A motorist's view in 1960 (left) and in 1974

(right) as they exited the inbound North Portal heading into Pittsburgh.

The Third Tube

In 1962, the South Hills Committee for

Improved Highways was formed. There was much talk of building a $104 million

South Hills Expressway, a six lane highway from the Liberty Tunnels to the

Washington County line. The expressway would roughly follow the present Route

51 to Route 88, then cut through Whitehall and South Park.

A part of the proposal was the widening

of the Liberty Bridge to six lanes and the boring of a third tunnel next to the

existing Liberty Tunnels, thus creating triplets as far as the tubes were

concerned. The chairman of the South Hills group declared that the expansion

of the bridge and tunnel were essential to the project.

Like so many other ideas that reached

the planning stages and gathered momentum along the way, the ambitious South

Hills Expressway project was cancelled, along with the corresponding expansion

of the bridge and tunnel. Lack of funding and strong opposition from Whitehall

residents doomed the initiative.

A Complete Tunnel Overhaul - 1974/1977

In December 1974, Trumbull Corporation

launched a long overdue $7.2 million renovation of the rapidly deteriorating

Twin Tubes. State Transportation Secretary Jacob G. Kassab labeled the 49-year old

tunnel a "dungeon" and personally led the effort to bring this project from the

planning stages to implementation.

Renovations included a new road bed,

installation of 3000 flourescent light fixtures, 44,000 feet of conduit, 454,000

feet of electrical wiring and new antenna cables for better AM Radio reception.

The long abandoned walkways were removed to enlarge the traffic lanes.

Work began in January 1975. The outbound

tube was closed first, with bi-directional traffic routed through the inbound side.

On December 19, 1975, the outbound side was opened to traffic. After the holiday

season ended, the inbound side was closed, with the bi-directional traffic flow

on the outbound side.

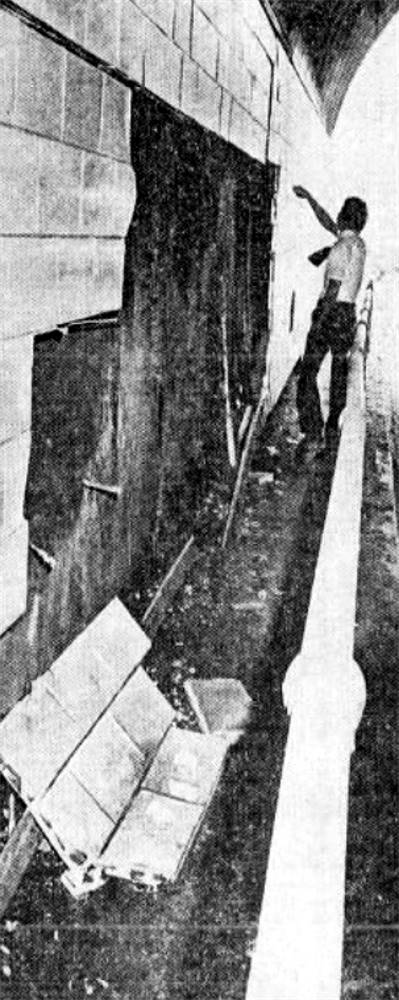

A large hole in the crumbling tile walls (left)

and broken sections of the railing along the walkway in October 1973.

Dirt and grime along the walkway had built up to a depth of over four inches

on long stretches of the walkway.

Another structural problem was falling chunks of the ceiling, which had

damaged a number of vehicles.

On the inside, the old tile walls were taken

down and years of dirt and grime were removed from the inside. The condition of the

concrete walls under the tile was bad, necessitating a near complete resurfacing.

They were then covered in an epoxy to increase brightness. Also installed were

17,000 feet of specially fabricated ceiling drains.

The outside facades of both portals were

also completely remodeled. The deteriorating concrete surface was covered in both

brown brick and COR-TEN steel siding, giving the tunnels what designers considered

a distinctive "Rust Belt" look.

Leaving town, bi-directional traffic at the

inbound tube in December 1975. The outbound portal is blocked off.

Concrete work near the southern portal

in December 1975.

Concrete work inside the Liberty Tunnels

in 1975.

In anticipation of the increased vehicle flow

and traffic congestion during rush hours in the restricted tubes, engineers installed

a large fan near the portal entrance to facilitate additional air flow through the

operational tube.

The ventilation system caused a lower height

restriction for vehicles entering the tunnel. Despite posted signs warning of the

new restrictions, truckers often wedged their rigs in the tunnel under the steel

I-beams supporting the auxiliary vent ducts. PennDot crews had to deflate the tires

and push the trucks out, blocking traffic for hours on occasions.

Working near the north portals (left)

and installing the additional ventilation system in 1975.

Workers installing drain pipes (left) in March

1975 and concrete work at the northern portal in September 1976.

The outbound tube was completed and opened

to traffic on December 19, 1975.

Another issue occurred on January 17, 1975,

when memories of the May 1924 Carbon Monoxide Crisis were again revisited. On this

day police were forced to close the tunnels for a short time when the auxiliary fan

malfunctioned and carbon monoxide levels reached dangerous levels.

After two years of traffic restrictions, work

was completed in February 1977. By that time the cost had risen to $10 million due to

the unexpected degree of damage to the interior walls. These were the last major

repairs done for the next three decades.

The COR-TEN siding and brown brick facade on the

Southern Portals gave them a distinct Rust Belt look.

Project Included Removing

Nearby Blight

Another improvement made during the tunnel

rehabilitation project was the clearing of the area near the Southern Portals

once occupied by "John's Lumber Company." The abandoned building and was destroyed

on November 23, 1973 in a four-alarm fire and had been sitting in its charred state

ever since.

John's Lumber Company goes up in flames (left) on

November 23, 1973. The Southern Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

stand in the background of a March 1974 image showing the burnt remains of the lumber

yard.

The city purchased the former lumber yard and

the adjacent used car lot. The improvement of this parcel of land was added to the

reconstruction effort. By the time the tunnel project was completed in 1977, the land

had been cleared, but not landscaped, a temporary removal of the blight that had

become an eyesore to South Hills residents.

Unfortunately, the effort ended there, and

within a couple years the area once again had that all too familiar urban blight

look. The city rented the land to an auto repairman, who began storing salvaged

vehicles there. An abandoned flat-bed trailer and an old school bus found there way

onto the property, along with a myriad selection of garbage.

An abandoned flat-bed trailer and other items

of garbage sit on the land next to the Liberty Tunnels.

It wasn't until the mid-1980s that the

condition of the area was properly addressed. The land was again cleared and,

this time, landscaped with a donation from the Western Pennsylvania

Conservancy.

PAT South Busway - 1977

One effort at relieving traffic congestion

at the southern end of the tunnels was the PAT South Busway proposal.

In the late-1960s and early-1970s Allegheny County was experimenting with a new

mass transit system called Skybus. It would replace most streetcar and bus routes with a revolutionary

unmanned people mover.

Opponents of the Skybus system proposed

retaining the Port Authority bus fleet and moving traffic off the main roads

onto dedicated busways and creating a network of bus lanes downtown. One such

busway would be constructed in the South Hills, between the South Hills Junction and Glenbury Street in Overbrook.

This graphic showing the path of the proposed

South Busway appeared on October 15, 1971.

The Skybus system was eventually scrapped

and the busway proposals accepted. The South Busway went into operation in 1977.

It removed 95% of the bus traffic that traveled through the southern interchange

and into the tunnel.

This had a positive effect on lessening the

amount of traffic using the tunnels. However, considering the overall amount of car

and trucks still passing through the tubes this was only one piece in an overall

restructuring of the intersection.

The South Interchange - 1996/1999

Beginning in the 1930s, a number of

proposals were introduced to modernize the four-way intersection at the corner

of West Liberty Avenue and Saw Mill Run Boulevard to better facilitated the

numerous traffic patterns at the crowded intersection

The streetcar tracks were diverted to the

Palm Garden Tressel in 1939 and PAT bus traffic was diverted onto the South Busway

in 1978. Although helpful, these improvements did little to address the

ever-increasing flow of automobile traffic.

The Liberty Tunnels Interchange, shown in 2004,

was a major transporation improvement for South Hills residents.

Not until 1996 was the problem addressed.

At this time the intersection was used by 140,000 commuters daily. With the

pending reconstruction of the Fort Pitt Tunnels scheduled to begin in 2000,

and the expected increase of traffic through the Saw Mill Run Corridor due to

detours, the state finally acted on the issue.

Michael Baker Corp. was awarded a $40

million contract to design and build a new interchange. The ambitious project

was completed in just three years. The design involved several components,

including seven intersecting streets, 3,500 feet of connector roads, two bridges,

two box culverts, five retaining walls, drainage, lighting, signing and five

signalized intersections. In addition, PennDot had the roadbed inside the tunnels

replaced before the project began.

Photos from 2010 showing both the Southern

Portals (left) and the Northern Portals.

"Gateway To Suburbia"

Michael Baker Jr. Inc. recounts its experience

designing the multiple award-winning

Liberty Tunnels Interchange, and how software contributed to its success.

The Liberty Tunnels Interchange was

officially dedicated on November 19, 1999. The results were stunning, and

traffic flow through the intersection was dramatically improved.To the delight

of South Hills residents who used the Tubes for their morning and afternoon

commute, what was once a dreaded snarl of rush hour traffic became a simple

one or two light delay.

In addition to the new southern interchange,

engineers made improvements to the tunnels themselves, installing a cement roadbed

with reflective barriers on the sides, and repainting the walls. The smooth roadway,

and the ease of travel created by the modern interchange were huge upgrades in

convenience for South Hills travelers.

The Liberty Tunnels South Interchange

in December 2014.

Liberty Tunnels Reconstruction - 2008/2014

In 2008 work began on a comprehensive, $18.8

million overhaul of both the interior and exterior of the tunnels. The facades of

the southern and northern portals underwent a complete facelift.

The rustic outer brick facing was torn down,

exposing the original concrete exterior. Once the deteriorating concrete was removed

and shored up, decorative panels were installed that resembled the tunnel's original

appearance.

A 2008 artist's rendering of what the new

portals will look like after the reconstruction was completed in 2014.

In addition to the exterior work, extensive

repairs was done to the interior of the tubes. Cracks on the inner walls were

repaired, cross-sections renovated and the walls thoroughly cleaned and repainted.

Modern electrical lighting and safety systems were installed. The prime contractor

was Swank Construction Company.

Construction work was completed in the

early fall of 2014. For motorists in the South Hills and the City of Pittsburgh,

it was a fine day indeed. A historic landmark had been completely refurbished

and returned to it's original luster.

The completed Southern Portal entrance

in 2014.

Additional Tunnel Improvements - 2017/2018

In addition to the tunnel project, PennDot

also contracted Gulisek Construction to perform a $4.32 million improvement project

on the Liberty Tunnels South Interchange. The project ran from March to July 2017,

and included concrete patching, an asphalt overlay, bridge preservation, drainage

improvements, ADA curb cut ramp installation, signage and signal upgrades, ramp

reconstruction, and other miscellaneous construction activities at the Route 51

(Saw Mill Run Boulevard) and Route 19 (West Liberty Avenue) interchange.

The final phase of the Liberty Tunnel

rehabilitation project was put off until July 2017. The two year, $30.27 million

project was completed in December 2018. It included paving inside the tunnel,

upgrading the air monitoring and fire suppression system, and repairs to the roof

and retaining wall. The ventilation system was also overhauled.

An aerial view of the southern tunnel interchange

taken in December 2014. Approaching 100 years of age,

the Liberty Tunnels remain one of the primary gateways to the South Hills.

The Liberty Tunnels brought growth and

prosperity to the South Hills in the 1920s. Nearly a century later, the iconic

twin tubes are still the primary "Gateway to Suburbia" for the residents of

Brookline and the nearby South Hills communities, and in condition to continue

that role for years to come.

Photos Of The Liberty Tunnels

Click on images for larger pictures

♦ Additional Related Links ♦

The Southern Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

and downtown Pittsburgh beyond Mount Washington in June 2019.

Before the Liberty Tunnels - 1915

Workers installing a new sewer line

along West Liberty Avenue (left) in May 1915 near the base of Mount

Washington. A stone quarry stands along the hillside where the Liberty

Tunnels southern portals

would soon be constructed. The photo on the right shows a view looking north

along

West Liberty Avenue towards the Mount Washington hillside in July 1915.

West Liberty Avenue, looking north

from Pioneer Avenue toward the intersection with

Warrington Avenue in October 1915 (left) and again in December 1915.

Constructing the South Portals

Clearing The Hillside - 1920

Boring The Tubes - 1921

Dumping The Excavated Debris

A narrow gauge locomotive, formerly of the

Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad, preparing to move a

rail cars loaded with debris from the tunnel excavation to the landfill area

along Bausman Street.

A train of Western four-yard dump cars

discharging a load of debris along Bausman Street from the tunnel dig.

It was this landfill that helped create the roadbed and the tiered plateaus

that define lower McKinley Park.

Rail cars loaded with debris from the

inbound tube will be hauled to Bausman Street for dumping. At the time

this photo was taken, July 15, 1923, much of the construction work

was completed and the county began

the process of tearing down five frame structures that stood in the way

of the tunnel approaches.

Constructing the North Portals

The north end on July 15, 1923,

showing the retaining wall above the entrance nearly completed.

The northern portals in August 1923,

with the installation of electrical wiring underway.

The Northern Portals stand ready for

traffic on December 30, 1923. The tunnels were scheduled to open in a

couple weeks after air testing was completed. Note all traffic turns

towards Arlington Avenue, then still

called Brownsville Road, due to the absence of the Liberty Bridge, whose

construction had just begun.

Boring The Twin Tubes (1919-1922)

A plan of the drilling holes that was

used during the tunnel excavation.

Construction workers inside

the tunnel bore in April 1921.

Construction workers and a crane inside

the tunnel bore in April 1921.

Sidewalls, forms and traveling incline (left)

for concrete rail cars; Erecting steel forms for arch concrete.

The structural steel ribbing placed inside

the tunnels was spaced at different intervals to account for varying

environmental conditions. The use of steel H-beams reduced the

amount of timber used during construction.

Inbound motorists travel through the tunnel.

Ventilation shafts are visible at the mid-way point.

The South Hills Twin Tubes

Traffic at the Southern Portals was sparse

on this day in March 1924.

The southern portals of the Liberty

Tunnels, at the intersection of West Liberty Avenue and Saw Mill Run

Boulevard, in 1930. This crossroads was deemed one of the ten deadliest traffic locations in the City

of Pittsburgh by the Bureau of Traffic Planning. This was a time

when increasing automobile,

street car and pedestrian traffic combined to create a lethal mix,

and fatal accidents

were becoming a serious problem. In July 1930, the Pittsburgh Press

deemed this

to be one of the worst in the city. A city-wide effort was initiated to

help

make several heavily used roadways safer for all forms of traffic.

A traffic safety sign at the entrance to the

Tubes in 1932.

The southern portals, at the intersection

of West Liberty Avenue and Saw Mill Run Boulevard, in 1932.

The southern portals, at the intersection

of West Liberty Avenue and Saw Mill Run Boulevard, in 1932.

Looking south towards Brookline from atop

the south portals of the Liberty Tunnels in 1932. Pioneer Avenue is

visible to the left, heading up the hill towards the homes in the Paul Place

Plan and West Liberty School.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

in 1936.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

on February 28, 1937.

The wider newspaper clipping of the same

February 28, 1937 photo shown above.

Postcard image of the south end of the

Liberty Tunnels in 1937. The sign above the tunnel portals

announces the Allegheny County Free Fair at South Park.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

on January 29, 1946.

Soldiers of the Pennsylvania National Guard

were in Pittsburgh to clear snow and restore order after

the Thanksgiving Day Blizzard of 1950. This photo was taken on November 30, five days

after the storm, showing soldiers directing traffic outside the Liberty

Tunnels.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

in 1954.

The south plaza roadway was completely

refurbished and bridge repairs done in May 1954.

The South Portals on March 20,

1956.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

as printed in the Pittsburgh Press on November 10, 1968.

Morning rush hour traffic approaches the

south portals on August 9, 1970.

The Southern Portals in August

1974.

Traffic congestion at the South Portals

of the Liberty Tunnels in 1974.

Norfolk and Western tracks alongside the piers

for the new Palm Garden Busway Bridge on March 4, 1975.

The southern portals of the Liberty Tunnels stand below along Saw Mill

Run.

The South Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

in 1941 (left) and in 2001. The original facade of the tunnels

had been replaced with the brown brick and steel exterior during a 1975

renovation.

Approaching the Liberty Tunnels

traffic interchange and the South Portals in 2011.

The South Portals on March 24,

2020.

The Northern Portals

The City of Pittsburgh looking from north

to south. Visible on the hillside across the river, above Carson Street

are the North Portals of the Liberty Tunnels. The year is 1924, shortly

after tunnel construction ended.

Work on the Liberty Bridge would begin in 1925. Until the bridge was completed

in 1928, motorists

entering the city from the south turned right onto McArdle Roadway, then left

onto Arlington

Avenue to Carson Street. The Smithfield Street Bridge was their gateway

to downtown.

Zooming in on the photo above to show

the northern portals in 1924.

The North Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

in December 1923. The tunnels opened to traffic one month later.

With no bridge in place, both inbound and outbound lanes turned towards

Arlington Avenue.

The outbound Northern Portal, shown here

in 1926.

The North Portal and traffic circle in 1928.

Only four years after opening, the white facade of

the tunnel entrance already shows the effects of the sooty atmosphere of the

Smokey City.

The inbound North Portal (left) in 1933,

as maintenance crews work to clear the busy roadway after a mudslide.

The Mount Washington hillside is unstable, and landslides became a

persistent problem to this day.

Looking down from above the North Portals

on April 20, 1933.

The North Portals of the Liberty Tunnels after

the addition of traffic signals in 1938.

A view of the North Portals from Arlington

Avenue in August 1939.

The Liberty Tunnels in 1939, after the

installation of new lighting and a new road bed.

By 1940 the traffic circle had been removed

and replaced by Traffic Division officers. Traffic patterns also changed

slightly. Coming inbound out of the tunnels there was no more left turns onto

McCardle Roadway.

Approaching the tunnels, left turns to McCardle were also eliminated.

Exiting the Liberty Tunnels inbound North

Portal around noontime in 1947. This was what motorists saw as they

entered the dark, murky atmosphere of the "Smokey City" before environmental

controls were established.

County Police divert all traffic from

entering the Liberty Bridge and downtown Pittsburgh after the Thanksgiving

Day Blizzard of 1950. Downtown was off limits while city workers and National

Guardsmen cleared snow.

Approaching the North Portals of the Liberty

Tunnels in the 1950s.

Cars exiting the inbound Northern Portal

(left) in 1953 and entering the outbound portal in 1970.

The Northern Portals in February

1974.

The Northern Portals on June 7,

1974.

The Northern Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

in 2011.

The Northern Portals of the Liberty Tunnels

during initial reconstruction work in 2012.

Thousands Overcome By Automobile Exhaust

May 10, 1924

A crowd gathers outside the Liberty Tunnels

North Portals during the carbon monoxide crisis in the tubes.

Courage, Cool Courage,

Looms Large As Day's

Crisis Reveals Unsung Heroes

By William G. Lytle,

Jr.

Panic, heroism, cool courage - the raw

elements of disaster - rode the confusion that jammed the exits of the Liberty

Tunnels today when poison death swept its vapors through the packed tunnels,

smothering more than a score of persons into insensibility.

Into a half-hour of frightful chaos,

scenes of bravery, fear and disorder that passed beyond description crushed

their speeding pictures when a traffic jam at the north end of the tunnel

caused the line to slow up for a period so long that deadly fumes had time

to do their work.

Minutes when death for trapped motorists

and pedestrians was imminent transformed ordinary men into heroes. Men who had

risen from their breakfast tables with never a thought but to resume their daily

routine found themselves cast in the lists of heroism by fate.

Hundreds of persons milled around the

tunnel mouth, breathless. Those who had fled in time came staggering from the

entrances whence the gas murk rolled. They were gasping, eyes bloodshot,

hearts pounding.

PLUNGE INTO TUBES

Policemen, firemen, motorcycle officers,

the disaster squads of the United States bureau of mines, civilians, plunged

into the tubes where men and women lay unconscious in their automobiles

stricken where the gas terror had overtaken them.

Lights were obscured within the tubes

by the density of the gas. Rescuers groped through the darkness, fumbling

from car to car, soaked handkerchiefs over their faces, hunting for those

who had fallen.

Thomas Morrison and C.W. Hooker, two

patrolmen, were two whose bravery stands forth as something to be remembered.

With no gas masks, both fought their way hundreds of yards into the death

trap. They carried out, on their backs, four persons, who would have died

but for their arrival. Morrison found one man sprawled in the bottom of a

coupe, his hands grasping at the door. The fact that there was no motor key

in the car indicated that a panic-stricken companion had fled, leaving the

other occupant of the car to his fate.

There were many brave men like

Hooker and Morrison who performed mighty deeds in that welter of foundered

cars and unconscious men and women, and vanished when their work was done

so that their names are unknown.

The story of Charles Maire, an

electrician on the Panhandle division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, was

pieced together, after he was found lying on his face beside the railroad

tracks, 200 yards away from the scene of the disaster. Those who found

Maire think he was among the first to rush to the tunnel to aid in resue

work when the alarm was sounded.

TORTURED WITH GAS

After helping to carry out those who

had dropped, his own lungs tortured with the gas, his heart laboring

desperately, Maire wandered vaguely back toward the work he had left.

There the gas felled him, without warning. It acts that way.

A workman, shoving his dazed, gas

scarlet face into a blue handkerchief, staggered from an orifice between

the tubes. He swayed a moment, speechless. No one noticed him for a short

interval, so great was the confusion. He waved his arms. Then without

warning, exactly as if someone had kicked him in the knees from behind,

the man's legs doubled up and he fell on his face on the concrete

pavement.

Rescuers picked the victim up.

He fought them madly, still silently and in the clutch of the gas, while

he grabbed at his throat with horrible gestures.

Officers and men of the Pittsburgh

police force never distinguished themselves with greater gallantry than

in the black depths of the tunnel.

First aid is given to policemen overcome by

carbon monoxide fumes while rescuing people from inside the tunnels.

ORDER RESTORED

As order was forced upon the excited,

jabbering throng at the mouth, a rift in the crowd showed a row of men in

the gray-black uniform of the motorcycle service, writhing on the curb.

Rescuers had oxygen tubes to the mouth of each man.

One officer slumped on his back on

the cushion of an automobile, his gunbelt flapping loosely, his shirt open,

his chest rising slowly with each painful breath. His comrade at his side

was able to sit up, supporting an oxygen tube with trembling arms and

sucking at the good air as if his strained body would never get its fill

of oxygen.

These men had raced into the tubes

time and again. Almost overcome, their courage had driven them back for

more. When the last victim was carried out, the men of the motorcycle

division still beat back once more into the evil-smelling, choking fumes

lest some persons might still be fighting for life in one of the

abandoned cars.

As the last cars were towed out

and certainty was established that no other person remained in the tubes,

the men of the motorcycle squads toppled to the street and lay there.

They had fought the fight to the end.

Alexander Tyhurst and Roy Brandt,

two patrolmen, knocked down connecting doors within the tubes and allowed

the passage of air. They found three of their comrades, Cox, Kepeler

and Sergeant A.L. Jacks, huddled against the wall and carried them to

safety.

Ammonia was sprayed in the tubes

by the disaster squads of the bureau of mines to counteract the carbon

monoxide.

Brave men and their work alone

held back certain tragedy, when the Liberty Tunnel disaster counted first

toll in Pittsburgh's "stupendous folly," the street car strike.

* Reprinted from the

Pittsburgh Press - May 10, 1924 *

Thousands of Pittsburghers, accustomed to

going to work in streetcars, jammed into motor vehicles in an effort

to get to their places of employment. Traffic jams, like this one on

West Liberty Avenue, were typical of

of the road conditions that prevailed on virtually every artery leading

to downtown Pittsburgh.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Cars Jam At Mouth

And Tube Blocked

More than two score of men and women

are in a serious condition as the result of being overcome by fumes in the

new Liberty Tunnels today when the increased automobile traffic due to the

streetcar strike caused two lines of cars to be blocked for the entire

length of the tunnel, one and one-fifth miles.

The tubes were closed after the jam

but later were reopened with a motorcycle patrol directing the

cars.

For more than an hour police officers,

firemen, rescue workers from the United States bureau of mines, and

volunteers fought the fumes to rescue the motorists. Scores of others

abandoned their cars when they realized the danger of their situation and

came staggering from the tube in a dazed state.

Police officers, with no protection

other than handkerchiefs over their faces, worked until they dropped and had

to be removed by their fellow rescue workers. Firemen with gas masks and

search lights assisted this work as did a crew of twelve men from the

government bureau of Schenley Park.

Inability of traffic officers to

keep autombiles moving away from the Brownsville Avenue end of the tube

onto Carson Street caused the cars to become stalled back in the tube. For

a few minutes the passengers and driver in the automobile thought the

blockade was only temporary and would soon be relieved. When they realized

the jam was critical, they abandoned their cars and ran toward the ends of

the tube for safety.

POLICE TAKE CHARGE

Assistant Superintendent of Police

Joseph Dye, assisted by all of the police commissioners, many lieutenants

and squads of patrolmen, assumed charge of the confused situation and

directed the rescue work. Patrol wagons, ambulances and fire equipment

waited at the mouth of the tunnel to be of service.

Many of those removed from the

gas-filled tubes were given first aid treatment at the homes of Fred

Eberle on Brownsville Road. Others were taken directly to one of the