|

This historical essay attempts to explore

the history of the South Hills region known as Brookline, formed in 1905. Actually,

this area has a rich history dating back much further, to the 1750s and the days

when taxes were paid to the King of England

Much of the information presented here

was retrieved from old Brookline Journal articles, the University of Pittsburgh Online Digital Archive, including the Pittsburgh City Photographer

Collection, and articles retrieved from the search engine at newspapers.com.

Our story has been supplemented over the

years by personal recollections of long-time Brookline residents, bits and pieces

from individual scrapbooks and plenty of additional research. Much of this research,

data and images has been merged into this essay, a comprehensive look back in

time.

Explore the highlighted links below, along

with additional links located throughout the text, for more detailed information

on the history of the Brookline community. For a supplemental resource, visit

our Brookline Connection facebook page.

* Last Updated: December 18, 2023 *

Brookline Boulevard, near the intersection with Glenarm Avenue, in 1933.

Prior to 1900, Brookline Boulevard was a

dirt roadway, known as Hunter Avenue (from West Liberty to Pioneer)

and Knowlson Avenue (from Pioneer to

Whited), that connected the many family owned farms that made up the

Brookline countryside.

The Beauty Of A Morning Sunrise In Brookline

It seems like all the colors in the visual

spectrum are captured in this Christopher Jamison

picture of "A Sunrise Over Brookline," taken on January 25, 2017.

A Great City Will Grow

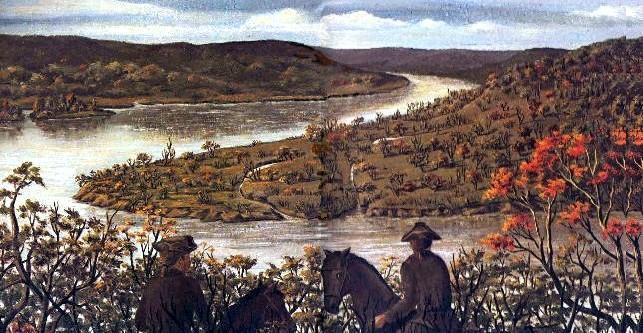

On November 23, 1753, George Washington, a twenty-one year old major in the British Colonial Army,

surveyed the land surrounding the junction of the Monongahela River

and the Belle Riviere. The young major predicted that on this spot

there would someday grow a great city. He recommended that militia by

dispatched with all haste to construct a fort.

Due to the strategic significance of

the land now known as "The Point", the junction was a prized possession to

any occupying force, offering control of all river traffic to the western

frontier. The French needed dominance over the Ohio River Valley to

consolidate their colonial interests in Canada (then known as New France)

and Louisiana. The British had other designs for the region. The crown and

increasing numbers of colonial settlers were looking to expand their

territorial boundaries beyond the Appalachians.

The French insisted that they had

claim to the region by right of first discovery. The British countered

that the land fell under their control by virtue of a treaty with the

Five-Nation Iroquois Confederacy. Both empires felt that their claims were

justified, and each expended great manpower and resources to gain dominance

over this advantagious location.

The British and The French

Heeding Washington's advice,

the British rushed a small garrison to the river junction and constructed a

small stockade called Fort Prince George. The French responded by sending

strong force, including many of their indian allies, that overwhelmed the vastly

outnumbered British. The garrison surrendered on April 17, 1754 and began the

long march back to Virginia. A new, much larger French outpost was built on the

spot, named Fort Duquesne.

In the meantime, Major Washington

had been dispatched with a regiment of Virginians to reinforce the garrison.

Washington's troops first encountered the French at a skirmish known as the

Jumonville Affair. The french patrol was routed and their commander killed.

On July 4, 1754, the French counterattacked in force. Washington and his

militiamen were beseiged at Fort Necessity and compelled to

surrender.

These local events marked the formal

beginning of the French and Indian War. To the chagrin of the British, the

empire of France now had complete control over the region and, most

importantly, the river junction.

In February of 1755, General Edward

Braddock was sent with two colonial regiments and 500 British

regulars, including artillery, to evict the French force. On July 8, 1755,

the British column was ambushed as it approached Fort Duquesne and suffered

another serious setback. Now a colonel, George Washington was present for

this monumental defeat. After the death of General Braddock, Washington took

charge and led the retreat back to Virginia.

The defeat at the Battle of the

Monongahela reverberated throughout the British Colonial Empire. Stung by

this loss, and determined to regain control of the region, the British struck

back three years later. On November 25, 1758, General John Forbes and an

army of 6000 British and Colonial troops forced the French to burn their

fort and retreat north. Forbes and his men had claimed

the river junction for the British Empire once and for all.

General Forbes ordered the

construction of a much larger and stronger fort. It was built over the

ruins of Fort Duquesne and named Fort Pitt. Forbes christened the area

Pittsborough. The village was chartered in 1759, named in honor

of the Prime Minister of England, William Pitt.

The colony at Pittsborough grew

rapidly around the fort, which was one of the largest British strongholds

in North America. Settlers and traders began to migrate to the surrounding

areas, including the rolling hills to the south of Coal Hill.

These early pioneers provided goods and services for the many British

troops and the growing frontier population.

Indians on the Warpath

By 1763, the final year of

the French and Indian War, the British had control of much of northeastern

North America. Most of the native Indian tribes were displeased by their

treatment from the British occupiers. The main concern of the Indians was

the continued settlement of people along the western frontier, which in

1763, included the Ohio River basin.

An Indian leader named Pontiac began

organizing many Indian tribes together to rebel against the British.

Pontiac's force included groups from the Delaware, Huron, Illinois,

Kickapoo, Miami, Potawatomie, Seneca, Shawnee, Ottawa, and Chippewa tribes.

An Indian War, known as Pontiac's War, began in 1763.

Pontiac wanted to drive the British

back to the eastern side of the Appalachian Mountains. Many small British

outposts were overrun and the Indians were on the verge of total victory.

The only remaining outposts west of the Appalachians were at Fort Detroit,

Fort Pitt, Fort Ligonier and a handful of other outposts.

The Siege of Pittsborough lasted

eighty-six days from May to August 1763.

In May of 1763, the Indians attacked.

Their assault began in the north and swept south towards the village of

Pittsborough. The natives burned all cabins and massacred all of the white

settlers in the outlying areas. Only those fortunate enough to find sanctuary

inside the fort survived. From May 27 to August 9, Pontiac's warriors laid

seige to Fort Pitt. During this time they made several unsuccessful attempts

to storm the fort.

British Colonel Henry Bouquet led

a relief expedition, which was ambushed as they approached the village.

Bouquet's force successfully counterattacked during the Battle of Bushy Run and defeated the natives. This victory

effectively lifted the seige of Pittsborough. Without the assistance of the

French, who were near surrender themselves, the Indians were soon forced to

abandon their campaign to drive the British from their lands. The frontier

was now open to westward colonial expansion and settlement.

Colonel Bouquet's Highlanders defeat

Pontiac's warriors at the Battle of Bushy Run.

Settlers once again began to migrate

into the area, and Pittsborough again began to build and expand. The restless

natives, now settled in Ohio, remained a deterent to further westward

expansion. Sporadic hostilities continued off and on for three years.

Fort Pitt became a staging area for

several military expeditions against the native tribes. Not until 1766 was

a formal treaty signed. Despite the agreement, conflicts persisted along the

upper Allegheny River until 1779, and Fort Pitt remained a valuable military

bastion.

Control of the fort passed to the

colonial militia in 1772. The British garrisons abandoned the area never

to return. During the War of Independence, there was very little activity

in the western part of Pennsylvania. The majority of the conflict was

fought in the eastern coastal theatre.

In 1783, that conflict ended and a

new nation was born, the United States of America. Fort Pitt remained a

United States Army facility until permanently decommissioned in 1797. The

fort was dismantled and the materials used in local construction

projects.

Rapid Development of Pittsburgh

After the end of the Revolutionary War,

the borough of Pittsburgh began to expand at a more rapid pace. After years

of being a garrison town, the town now found a new identity. With frontier

expansion booming, Pittsburgh soon became known as the "Gateway to the

West."

The discovery of valuable natural

resources and reliable river passages made Pittsburgh an important stop

for migrant settlers on their journey west. It also became a valuable hub

for commerce and shipping.

This fueled the expansion and growth

of industry in Pittsburgh. Gristmills, print shops, glassworks, ship building

and the iron

industry flourished. By

the dawn of the 19th century, millions of people heading west traveled through

the area. The City of Pittsburgh was officially chartered in 1816.

The Carnegie Steel Works in Homestead. The

iron and steel industry flourished throughout the Pittsburgh area.

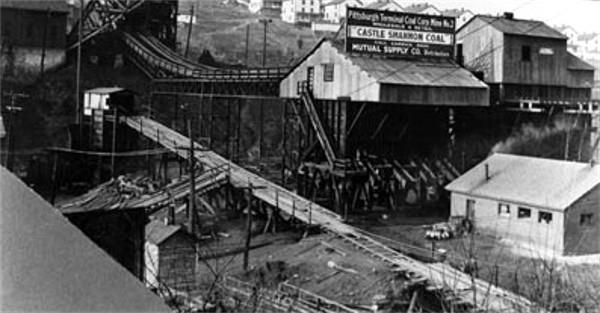

The abundance of coal in the

nearby hills led to the rapid development of the coal industry, which fed

the fires of the expanding industrial base, not to mention the home heating

needs of the growing local population. Numerous mining

ventures moved into the

lands east and south of the city.

The rolling, well-watered lands to

the south of Coal Hill were also considered prime farmland. Family farms

were a common site throughout the South Hills, including West Liberty Borough

and the present-day Brookline area.

Early Settlement of the South Hills

After the American Revolution, soldiers

of the Pennsylvania Militia were granted land by the State Legislature in lieu

of payment in gold and silver for their services during the War of Independence.

These veterans filed their claims in Philadelphia and became the first official

American settlers in the South Hills. A track of 395 acres, patented in 1786 to

David Strawbridge, in pursuance of the Virginia Certificate, was called "Castle

Shanahan."

David Strawbridge's 1786 land grant

that later became the municipality of Castle Shannon.

Another former militiaman, Joseph

McDermutt, filed his claim for 240 acres along Oak Hill. His land was

called "The Hermits Cell" and occupied much of the present-day 19th Ward

of Brookline.

<Survey Maps and Deeds of Original South Hills

Land Grants>

A search of old records reveals the

family names of Strawbridge, McKee, Shawhan, Kennedy, Fleming, Hunter,

Hayes, McDermutt, McDowell, Hughey, Broddy, and Brison. In the 19th

Century, we find such families as Espy, Plummer, Paul, Lang, Schaffner,

Kerr, Sylvester, Fetterman and Knowlson. The area became a prosperous farming

district.

Prior to the erection of Allegheny

County in 1788, the Pittsburgh district was part of Westmoreland and Washington

Counties. Civic-minded citizens had to travel long distances over poor roads in

order to cast their ballot on election days.

The earliest voting place was at

Shawhen's Square (later Colonel Espy's Tanyards) at Pioneer and West Liberty

Avenues. After 1788, they voted at Obey's Place on Carson Street, where the

Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Company station now stands.

St. Clair Township, named in honor of

General Arthur St. Clair, was a massive township stretching fifteen miles to the

south and varying in width from six to ten miles. The northern township border

was the Monongahela River, between the mouths of Chartiers Creek and Streets Run

Creek. The township was as large as many counties in other parts of the

state.

Formation Of Allegheny County

Allegheny County was formed on September

24, 1788. The county was made up of land previously a part of Westmoreland and

Washington Counties. It was formed due to pressure from settlers living in the

area around Pittsburgh, which became the county seat in 1791. Allegheny County

originally extended north to the shores of Lake Erie. It was reduced to its

current borders by 1800.

Many of Brookline's earliest landowners

were signatories on the initial petition for the creation of the new County. At

that time of the county's formation, what would become the Brookline area was

sparsely populated fertile land located in the lower district of

St. Clair Township.

<1787 Petition with Signatories for

the Creation of Allegheny County>

Signatories include Joseph McDermutt,

David Kennedy, Joseph McDowell, Robert Shawhen and John McKee,

all prominent landowners of property that make up the boundaries of

present-day Brookline.

Upon the erection of Allegheny County

the court proceeded to divide the county into three distinct districts. The

first included the townships south and west of the Ohio and Monongahela Rivers.

The second district was located between the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers,

and the third included land north of the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers.

The first section included three

townships: Moon, St Clair and Mifflin. At that time, St. Clair Township

was made up of the southeastern corner of present-day South Fayette Township,

part of Snowden Township, the whole of Baldwin, Scott, Bethel, Upper and Lower

St. Clair Townships. In 1805, Nathaniel Plumer, who resided in land that is

now part of present-day Brookline, was named as one of the three township

commissioners.

Lower St. Clair Township

In 1806, deemed too large to adequately

maintain, St. Clair Township was divided into the separate municipalities of Upper

and Lower St. Clair. Within the boundaries of Lower St. Clair Township were the

present-day communities of West End, Mount Washington, South Side, Beechview,

Brookline, Banksville, Beltzhoover, Mount Oliver, Bon Air, Knoxville, Allentown,

Carrick, Overbrook and St. Clair Village.

In the 1830s, the main population centers

were along the Monongahela River, where factory production and coal mining were

booming in the areas of Temperanceville, South Pittsburgh, Birmingham and East

Birmingham. These heavily populated and industrialized areas soon left the township

to form their own boroughs. Another significant parcel of territory was ceded in 1844,

when Baldwin Township was chartered.

Map from 1850 showing Upper and Lower

St. Clair Townships. The original St. Clair Township included

both Upper and Lower St. Clair as well as the whole of Baldwin Township and

part of Snowden.

The Road from Washington is present-day West Liberty Avenue from the southern

border

of Lower St. Clair to Saw Mill Run Creek. It was then known as Plummer's Run.

To the south of Coal Hill, the rolling

terrain of West Liberty and the other nearby communities along Saw Mill Run were

what remained of Lower St. Clair Township. Despite the losses, in 1860 the population

of the township ranked fifth in the county at 4,617. That number grew to 5,322 by the

end of the decade.

In 1860, the South Hills terrain was still

a predoninantly agricultural region. In the Brookline area, the largest of these were

operated by John and Elizabeth Paul, Richard Knowlson, Ephraim Hughey, David Hunter and Philip Fischer and David McKnight. These families lived off the

land and sold their surplus crops at the markets in Pittsburgh.

The coal industry began to move into the

South Hills in the mid-1860s, leading to a significant population increase as

laborers began migrating to mining villages with their families. In 1870 the value

of farms in the county was over $56,448,818, more than several states, and the

mineral resources almost incalculable. As the population and wealth increased,

emerging communities in Lower St. Clair Township began the process of forming

separate municipalities.

♦ Saint Clair Village (1951-2010) ♦

(The final section of Lower St. Clair Township)

William Dilworth

A notable early settler in Lower St.

Clair Township was William Dilworth. William was born in 1791 when Pittsburgh was

still a straggling village connected by row boat ferries with the nearby

settlements of Allegheny (North Side) and Birmingham (South Side). His father

was an early entreprenuer in the local coal industry.

Coal mining was the first major

enterprise in the South Hills.

At age 21, Dilworth joined

General William Harrison's army during the 1812 campaign against the British

and Indians. After the war, William settled on Mount Washington. He opened

some of the first mines to supply Pittsburgh with coal. He was married in 1817

to Elizabeth Scott, daughter of Colonel Samuel Scott of Ross Township.

Dilworth built what may have been the

first school house in Lower St. Clair Township to give free schooling to the

children of the miners in his employ. He paid the teacher out of his pocket

and purchased books for the pupils. The school building was erected in 1820

near the present-day South Portal of the Liberty Tunnels.

William Dilworth paid $15 per acre for

the coal lands he purchased south of Pittsburgh. During the the latter part

of his life he sold parcels of the same land for $3000 per acre. In the mid-1830s

he was instrumental in building a court house and jail in Pittsburgh, and later

built the piers of the old Monongahela Bridge, which was destroyed in

the Great Fire of April 10, 1845.

In 1847, Dilworth was elected to the

Legislature and served one session. Later, in 1859, he had a church built,

possibly the first in the area, near the old school house at the junction of

West Liberty Avenue and Warrington Avenue.

West Liberty Borough

West Liberty Borough was incorporated on March 7, 1876. The borough boundaries were

drawn from the western part of Lower St. Clair Township, with Saw Mill Run

Creek being nearly identical with the eastern and northern boundaries. The

village proper was described as a small hamlet on the old Pittsburgh and

Washington road.

Elections were held on March 24

for the new borough officers, resulting in the following choices:

Justice of the Peace - John Curran;

Judge of Elections - John W. Patterson; Inspectors of Elections - James Curran,

Warren W. Patterson; Burgess - John W. Patterson; Council - William Hughes,

John Paul, Thomas Curran, George C. Becker, Thomas Hughes and Thomas Knowlson;

School Directors - James Gibson, William Haas, Chris Wilhelm, George R. Fisher,

Joseph Hughes and William Robinson; Registration Assessor - William Haas;

Principal Assessor - John B. Knowlson; Assistant Assessors - R. R. Bell,

William Robinson; Auditor - A. J. Oyer; Constable - W. J. McIlvaine.

An 1876 map of the Pittsburgh area

showing the City of Pittsburgh and West Liberty Borough.

While the adjacent areas of Mount

Washington and the countryside along the line of the Pittsburgh and Castle

Shannon Railroad, such as the village of Fairhaven, were comparatively thickly

settled, West Liberty was sparsely populated.

Most of the land was made up of

farms, with some residential areas that were principally occupied by men

employed in the numerous coal mines owned by William Dilworth.

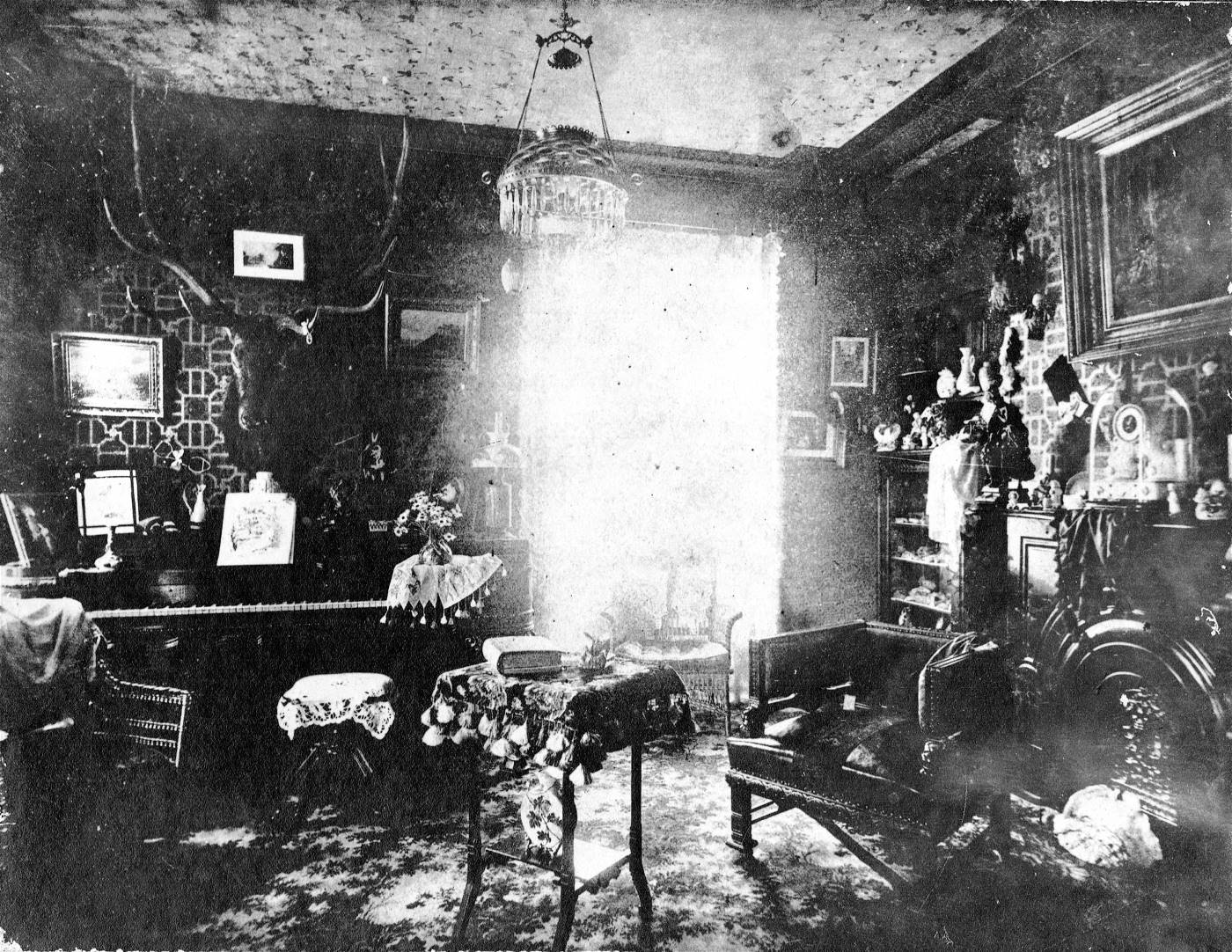

The home of George and Mary Beltzhoover along

the 1900 block of West Liberty Avenue (right), which

served as the Fetterman District Post Office from 1876 to 1907, and

the original West Liberty

Elementary School, shown here in 1912. It was the borough schoolhouse until

1898.

The population of West Liberty Borough

was 865 in 1880. The Fetterman Post Office district that covered the borough

boundaries was established in June 1876. Mary Beltzhoover, who resided along

West Liberty Avenue, just south of Capital Avenue, was the postmaster.

About this time, the first West Liberty

Elementary School was built along West Liberty Avenue at the bottom of Cape May

Avenue. This two room facility served the borough's children until 1898 when

a modern schoolhouse was built along Pioneer Avenue.

Map from 1876 showing West Liberty

Borough.

The surface of West Liberty Borough

was much the same as the rest of Allegheny County, hilly and broken.

Numerous small streams flow through it and springs are exceedingly abundant,

thus affording plenty of water and power for manufacturing purposes. Coal

was the staple production of the township, although agricultural pursuits

were extensively carried on.

By the dawn of the 20th century, mining

was still prevalent along the valley floors, with the remainder of Oak Hill

practically all farms. It was then a common sight on summer mornings to

see a procession of market wagons on their way to the city with produce,

then returning later that afternoon.

In 1890, John Price was elected to the

West Liberty Borough Council. This well-known resident was often referred to as

"the town's honest old patriot." When Price assumed his council role, the

borough was $14,000 in debt and had a total land valuation of $286,000. A man

with a vision, John Price worked tirelessly for the betterment of the

borough.

Price pointed out the possibilities of

the South Hills long before the Mount Washington Trolley Tunnel had been built

and was successful in securing rights of way for the traction lines where

others had failed. When the tunnel became a reality in 1904, he was proven

right and the borough prospered.

Residential and commercial development

began quickly and continued unabated. By the time of annexation in 1908, West

Liberty Borough was a growing municipality with a treasury balance of $8,000

and a land valuation of $3,687,0000. On the 27,000 acres of borough land there

were 2,000 homes and a population of 10,000.

In addition there were fifteen miles of

modern sewers and three and one-half miles of paved roads. Both Brookline and

Beechwood had modern boulevards ready for further development, and upcoming

improvements and expansions in the traction lines guaranteed that this real

estate boom would bring further millions in the near future.

January 6, 1908 was a great day for

Pittsburgh and the residents of West Liberty Borough, signalling the birth

of the Brookline, Beechwood and Bon Air communities.

It is interesting to note that in the

above article Beechview is referred to as Beechwood. The reason is that West

Liberty Borough was split down the middle by West Liberty Avenue, seperating

the area of Brookline to the west and Beechwood to the east. The borough extended

eastward only to Broadway Avenue. The Borough of Beechview, an independent

municipality, stood between Broadway Avenue and Banksville Road.

The following year, in 1909, Beechview

Borough was also annexed, then merged with Beechwood to comprise one city

neighborhood. That community took the name Beechview. So, after only one year

on the books, the name Beechwood was relegated to the history books, with but one

reminder of that name still on record, Beechwood Elementary School

Click

here to learn more about

Beechwood, Beechview and ... Orvilla?

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Life in West Liberty Borough was not always

as lovely as a Norman Rockwell glimpse of Americana. This tiny borough just south

of Pittsburgh also had a dark side, one more foreboding than anyone would care to

imagine.

In a remote corner of the borough near the

borders with Montooth, Beltzhoover, Knoxville and Baldwin, along Saw Mill Run near

High Bridge Station and the McKinley Bridge was a place that, beginning around 1890,

became a mecca for all sorts of illegal gaming, sporting and drinking activities.

It was said to be as dangerous as the Wild West near High Bridge Station.

These activities caused severe consternation

amongst the local citizenry and borough officials, who seemed helpless in their efforts

to restore peace and order. Years of frustration boiled over on May 31, 1903, when

a horrifying riot occurred that resulted in the deaths of two men, several injured

individuals and a near hanging.

♦ Monte Carlo in West Liberty Borough (1890-1903) ♦

♦ Deadly Riot in West Liberty Borough - May 31, 1903 ♦

Birth of Brookline

In the earliest days of frontier

settlement, an old Indian trail ran roughly along the path of Pioneer

Avenue and Castlegate Avenue to a small farm and trading post run by

the McNeeley family. The outpost was known to the natives as Chimney Town,

and the trail was called the Chimney Town Road. This may well have been

the earliest known designation of the area that was to one day become

Brookline.

The South Hills area was settled prior

to 1800. Many of these early pioneers were veterans of the Pennsylvania Militia

who had served in the American Revolution under General Washington. These men

were issued land grants as payment in lieu of gold and silver for their services.

These hardy souls tilled the soil

and developed a prosperous farming district. Colonel Boggs Grist Mill, near

the northern end of Pioneer Avenue, ground their grain. Colonel Espy's Tanyards,

near the southern end of Pioneer, furnished the leather for their boots,

saddles and harnesses.

The Kapsch family lived at 1114 Milan

Avenue. Joseph and Amelia Kapsch both immigrated from Austria and

settled in Brookline in 1906. They were farmers and the family was one of the

original twelve members

of Resurrection Parish. The picture shows some of the Kapsch children: Amelia,

Marie, Josephine,

Joseph and John, with their donkey in 1909. The family grew to eleven with the

addition of

Theodore, Leonard, Agnes, Lillian, Alfred and James. Agnes married Fred Daley

and

owned the Park Side Grill on Brookline Boulevard from 1948 to 1965.

Situated in Lower St. Clair Township,

the area we now call Brookline became part of the borough of West Liberty,

which also included much of present-day Beechview. From the colonial days until

the dawn of the 20th century, the area was sparsely developed.

The addition of trolley service to

the South Hills in 1901, followed by an electrical traction route the following

year and the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel opening in 1904 brought a new era

of prosperity to West Liberty Borough. Early lot plans like Fleming Place,

Hughey Farm and Paul Place brought investors and developers to the region and

soon the rural farming community began to take on a more urban

look.

The Birth of Brookline can be traced

to one defining moment, on March 12, 1905, when ten West Liberty farms on the

western side of the borough, comprising 500 acres, were sold to the West Liberty

Improvement Company. Farms belonging to Jane Reamer, David Hunter, William McNealy,

Dr. J.H. Wright, John Knowlson, Willison Hughey, Joseph McKnight, Philip Linn,

John Daube and Philip Fisher were now slated for residential and commercial

development.

The improvement company spent $700,000

on the farms, and invested a further $750,000 in grading and paving roads,

installing water and sewer line, and other infrastructure necessities to allow

for the immediate construction of homes. Pittsburgh Railways responded to the

news by immediately installing a service route into Brookline. The dye was cast

and the community of Brookline began to take on a life of its own.

Although originally intended as such,

Brookline was never incorporated as a separate and distinct municipality. It

was merged with the City of Pittsburgh on January 6, 1908, and made part of the

original 44th Ward. By the mid-1900s, it comprised the 21st to the 27th election

districts of the 19th Ward.

A 1905 Freehold Real Estate advertisement

showing Brookline's proximity to Pittsburgh.

♦ Fleming Place/Hughey Farms Real

Estate Advertisements (1902) ♦

♦ Freehold Real

Estate Advertisements (1904-1916) ♦

♦ Freehold Real

Estate Brochures (1921-1926) ♦

♦ Freehold Real

Estate Advertisements (1930) ♦

Beechview/Dormont Real Estate Ads

(1901-1917)

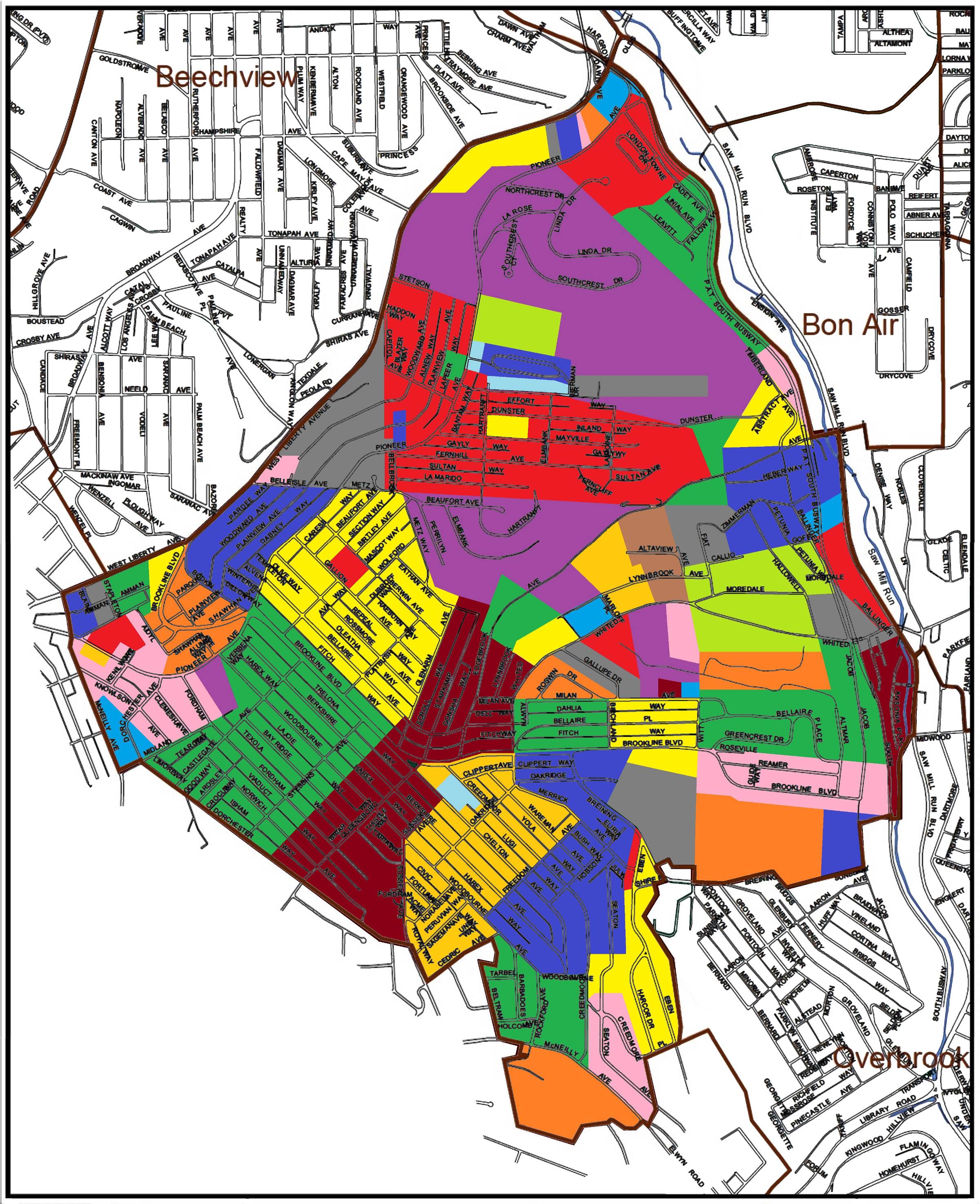

NOTE: Brookline now comprises part of the

19th and 32nd Wards of the City of Pittsburgh, and is made up of West Liberty,

Brookline, East Brookline (formerly part of Overbrook) and Ebenshire Village

(formerly part of Baldwin Township) - although the name "Brookline" is assigned

to the entire area.

See Maps Showing Brookline Subdivisions

Pioneer Avenue was a State Road

Pioneer Avenue was established in

1797 as the State Road from Pittsburgh to Washington. It was the only main

roadway to reach the city from the south. It was later known as the Upper

Road from Boggs Mill and also the Coal Hill and Upper St. Clair Turnpike

Road.

Until the 1830s Pioneer Avenue

remained an artery of major importance, connecting the old Township road

(now Warrington Avenue) with the Morgantown Road (now Banksville Road).

Much of present-day West Liberty Avenue (Washington Road) was considered

part of this intra-state thoroughfare.

Wenzell Avenue, which originally led from Pioneer Avenue

to Greentree Road, was laid out in 1832. Plummer's Run, now called West

Liberty Avenue, from the Bell House to Pioneer Avenue, was laid out in 1839.

Once established, Plummer's Run became the main north-south state roadway

and Pioneer Avenue was reduced to its present course and length.

Since the emerging southern communities

had no brick yards or saw mills, all builders' supplies had to be hauled over

these poor roads, with the wagons often sinking hub deep in mud.

West Liberty Avenue at the intersection

with Stetson Street in March 1915, before the roadway was widened.

When the original streetcar line

was installed along West Liberty Avenue in 1902, the road was paved with

Belgian block between the rails only. Off the narrow rail line the roadway

was dirt. It remained as such until 1915 when it was widened and improved.

Whited Street, Edgebrook Avenue

and Merrick/Breining/Glenbury Street were former Township Roads.

Brookline Boulevard existed as a narrow dirt path connecting the farms

east of West Liberty Avenue with these Township Roads. McNeilly Road

was another established Township Road.

With the exception of the

aforementioned streets, practically all other roadways in and around

present-day Brookline were created by virtue of lot plan developments,

principally by the West Liberty Development Company between 1905 and

1908.

Early Commercial Enterprises

Among the early commercial

enterprises were Espy's Tanyards, located at the southern end of Pioneer and

West Liberty Avenues, in present-day Dormont. Here, leather was supplied

for boots, saddles and harnesses.

Boggs Grist Mill and Schaffner's Wagon Building and Repair

Shop were situated at the

northern end of Pioneer and West Liberty Avenues.

At a later date, the Pittsburgh Coal Company's power plant, operated by the Hartley and Marshall

Company, was built at Wenzell Way and West Liberty Avenue. Across the road

was Kerr's Blacksmith and Horseshoe

Forge.

The Old Bell House Tavern, near West

Liberty Avenue and Warrington Avenue, in 1890.

Wilhelm's General Store, later known

as J. Claude Groceries was located across from Pauline Avenue on

West Liberty Avenue. The only other store was Algeo's, located further

south at Washington and Bower Hill Roads.

Food, drink, and lodging were to be had

at Beltzhoover's Tavern and the St. Clair Hotel, both located at

the foot of Capital Avenue. Hayes Tavern stood at the southern end of Pioneer

and West Liberty Avenue, and the Bell House Tavern and Hotel stood near the present-day Liberty Tunnels along Warrington Avenue.

Ways To Travel

Transportation from the South Hills

to Pittsburgh in the early days was slow and difficult. A long and arduous

wagon ride up Bausman Street and down Arlington Avenue was one alternative.

Another was to travel to Mount Washington and use

the inclines to traverse the hillsides.

Travelers that could afford a ticket

could reach the city by way of the narrow gauge Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad, which followed the general course of the

Shannon Drake streetcar line. Passengers would take the Haberman Avenue Cable

Car up to Mount Washington, then down the Castle Shannon Incline to Carson

Street. From there they traveled by horse car into the city.

The Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Incline

was in operation from 1890 to 1964.

Most of the coal mined around

Brookline was hauled on the P&CSRR through a Mount Washington tunnel, The

portal of the old coal tunnel was at the curve in Sycamore Street, directly

above the present-day transit tunnel. Once in Pittsburgh, the coal was

lowered to the factories along Carson Street using an incline.

By 1902, a horse-drawn streetcar line

was extended along the length of West Liberty Avenue to Mount Lebanon. This

single-track line passed the Brookline Junction at West Liberty and Hunter Avenue

(Brookline Boulevard). This line was soon electrified and extended to Castle

Shannon, making travel easier for South Hills residents, but there was still

no direct link to the city, except for the long trip over Mount

Washington.

Within a few short years, man made

huge strides in transportation. In 1903, the Wright Brothers historic

flight and Henry Ford's first automobile were actualities. The Mount

Washington Transit Tunnel through Coal Hill opened in 1904.

The South Hills Trolley Junction in 1906.

Note the billboard advertising homes in Brookline. On the hillside

above is a train of the Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad heading outbound

towards Overbrook.

The transit tunnel was a phenomenal

breakthrough for the South Hills. The Pittsburgh Railways Company soon

upgraded trolley service throughout the South Hills, with extensions built

to connect the many developing neighborhoods, along with an interurban

line to Charleroi.

These improvements shortened the trip

to Pittsburgh by miles and hours. It gave impetus to the West Liberty Development

Company and other real estate firms, from 1904 to 1908, to lay out streets and lots

in the portion of West Liberty Borough which was to become Brookline.

All Dirt Roads

At the turn of the 20th century all

roads were dirt and there were no sidewalks. The heavy traffic, which was

mostly horses and wagons, cut deep ruts into the roads so that in wet

weather the mud was often axle deep. Pedestrians fared no better.

Finally, Reverend Jones of

the Knowlson Methodist Church, located at the Brookline Junction with West

Liberty Avenue, with the help of a friend, secured funds to purchase

boards for a boardwalk. With the help of the community, the boards were

laid from the city line to the Old Bell House at

Saw Mill Run and West Liberty Avenue. This was the first public improvement

in the area.

A view of Rossmore Avenue, as seen from Pioneer

Avenue, in 1925.

The West Liberty Development Company began

laying out lots in the Brookline area in 1905. This new residential suburb attracted

so many people that, in February of 1907, West Liberty Borough voted for annexation

into the City of Pittsburgh.

On the first Monday of January, 1908,

the borough was annexed into the city as the 44th ward. Brookline and Beechview

became the 19th ward in 1910, when the City of Allegheny also became a part of the

growing metropolis.

A family in their horse and buggey approach

the intersection of Woodbourne and Sussex Avenue in 1924.

The paving of Brookline streets began

shortly after annexation. Some of the original roads to be paved were

Brookline Boulevard and streets nearby, like Berkshire, Bellaire and

Chelton.

These streets were covered with either

paving bricks or belgian block. Streets like Rossmore, Gallion, Woodbourne and

much of Pioneer Avenue were not paved until the mid-1920s. Parts of Berwin

Avenue remained unpaved until the 1950s.

Many Brookline streets were covered in

paving bricks, like Berkshire Avenue, shown here in 1923.

Other local streets were covered in larger, granite belgian blocks. Unlike todays

asphalt

covered roadways, these durable bricks were installed to stand the test of

time.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Are They Called

Cobblestones or Belgian Blocks?

There is some debate over the

proper term for the stones that were used to pave

many of Brookline's streets, like Rossmore, Flatbush, Capital and Birchland.

Were they called "cobblestones" or "belgian block."

The answer is belgian

block.

The official terminology

might sound a bit strange:

Setts, or Belgian Blocks (left) and

Cobblestones (right).

A SETT, usually referred to in the

plural and known in some places as a Belgian block, is a broadly rectangular

quarried stone used for paving roads. Formerly in more widespread use, it is

now encountered more as a decorative stone paving in landscape

architecture.

Setts are often idiomatically referred

to as "cobbles", although a sett is distinct from a cobblestone by being quarried

or shaped to a regular form, whereas the latter is generally of a naturally

occurring form. Setts are usually made of granite.

For a more detailed history

of setts, visit Wikipedia (Setts).

Workers cutting belgian block for use along

West Liberty Avenue in 1915 (left) and Rossmore Avenue in 2004.

The belgian block on Rossmore Avenue was put down in 1925.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Street Paving

In Pittsburgh

Well into the 19th century, Pittsburgh

roads were mostly unpaved. Early efforts at providing a durable surface on

roadways included using wood blocks, round cobblestones and crushed rock.

These methods were unreliable, and often deteriorated quickly.

Other, more expensive alternatives were

the use of vitrified paving bricks, belgian block or sheet asphalt. As the

years passed and the benefits of a smooth, reliable surface became evident,

these three options became the standard for Pittsburgh streets.

As the city grew, there also arose a

demand for better roads. Only a few main streets were paved with municipal

funds. The cost of paving all streets, however, was well beyond the limits

of the city coffers.

On April 2, 1870, the Pennsylvania

Legislature passed the Penn Avenue Act, which assessed a tax on abutting

property owners to pay for street paving. After this, the practice of

paving roadways became standard in middle to upper-class neighborhoods,

but was mostly rejected by the residents of working-class

communities.

West Liberty Avenue, looking north from the

Brookline Junction in June 1916, covered in belgian block.

When Pittsburgh roads were paved,

the cheapest method brick and belgian block. This was due to the paving

bricks being forged in foundries close to the city, and the block being

easily obtainable from nearby quarries.

Up until the 1930s, the granite

belgian block was preferred for use on heavily traveled roadways and also

on hilly streets because it provided better traction. Paving bricks were

selected for mostly level street surfaces that saw moderate traffic usage.

Outside the city limits, asphalt was the primary choice.

Due to the abundance of hills,

Pittsburgh was well-known for its belgian block roadways. In 1916,

the city ranked third in the nation with over 230 miles of block-covered

streets. The top two cities were Philadelphia and New York, both with

over 400 miles of roads covered in belgian block.

Berwin Avenue is covered in red paving bricks

and Beaufort Avenue in Belgian Block - April 2014.

Here in Brookline, most streets

were paved in either paving bricks or belgian block. The ratio or brick to

block was close to 50/50. Some streets with a mix of level and hilly stretches

were paved with both brick and block. Asphalt, and later concrete, were used

sparingly in Brookline until the 1940s.

Today, most streets throughout the

city are covered in asphalt or concrete. Vintage brick and block roadways have

diminished dramatically in number. As a testament to their durability, these

old road surfaces often provide the solid base for the smooth black

top.

The same can be said for the streets

in Brookline. However, there are still several brick and block streets that

have stood the test of time, providing motorists with a historic, and often

rumbling, reminder of Pittsburgh's past.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Where Did Brookline's Paving

Bricks and Belgian Block Come From?

During some water line repair work on

Freedom Avenue, a section of red paving bricks were removed and stacked

along the sidewalk. Once the utility line was back in service and the hole

filled, the paving bricks would be put back in place. This was one of the

main benefits of using the bricks.

The bricks that sat along the side

of Freedom Avenue were stamped "C.P. Mayer Co. - Bridgeville." As it turns

out, the C.P. Mayer Company provided the majority of the pavers used on

Brookline streets.

The brick works was founded in 1903 by

Casper Peter Mayer, a Bridgeville industrialist. The C.P. Mayer Company supplied

the majority of paving bricks used for roads in the South Hills. The dense and

durable pavers were so well made that, after a century, they can be removed from

present-day road surfaces, cleaned and put back in place as good as

new.

Our Belgian Block came from a bit further

away. In the 1890s, the city contracted with Keeling, Ridge and Company for the

granite blocks used for curbs and street paving. They obtained their product from

a quarry near Connellsville. From 1899 to 1950, Booth and Flinn, Ltd. was one of

the primary contractors for streets and other city infrastructure projects. Booth

and Flinn obtained their granite from their own quarry located west of Ligonier

at Longbridge, along the Ligonier Valley Railroad.

Workers at Booth and Flinn's granite

quarry near Ligonier, Pennsylvania.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on June 17,

1978, noted that because of the location of the Booth and Flinn quarry, granite

paving blocks laid in the 1900s are, here in Pittsburgh and Western PA,

officially refered to as, not Setts or Belgian Block, but "Ligonier

Blocks."

It is a shame that, over the years, so

many of the roads paved in Mayer bricks were not well maintained and eventually

paved over. If more of these road surfaces had been kept in service, the city

would have much less of a burden when it comes to asphalt road

resurfacing.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Street Sweepers

- The Hokey Man

Looking back through old photos of brick

and block streets, one thing always seems to be present, dotted in small clumps here

and there. Horses had no pride when it came to taking a dump. Anywhere was convenient

for those beasts of burden.

Who cleaned up all that mess on

a daily basis? The Hokey Man, that's who.

A Hokey Man, shown in 1916, cleaning some

waste off of a block roadway in Pittsburgh.

Where the name "hokey" came from is a mystery,

but these street sweepers were quite important municipal employees. With their push

cart, shovel and broom, these men toiled daily to keep the roadways clear of trash

and other waste. The companies that owned the city's toll bridges employed their own

hokies to keep the wooden roadbeds free of debris.

Street Car Service

The first streetcar railway south of

the Monongahela River was a horse-drawn car line, which operated from Carson

Street to Thirtieth Street. In the winter the floor was covered with straw

to keep the passengers feet warm. Horse-drawn rail traffic was established

in the South Hills in the early 1800s, but there were only a few routes

available.

The first electric cars were used

in this part of the city in 1890 and were controlled by the Pittsburgh and

Birmingham Traction Company. The cars seated twenty-five people. One such

route extended from Warrington Avenue south along West Liberty Avenue

to Mount Lebanon.

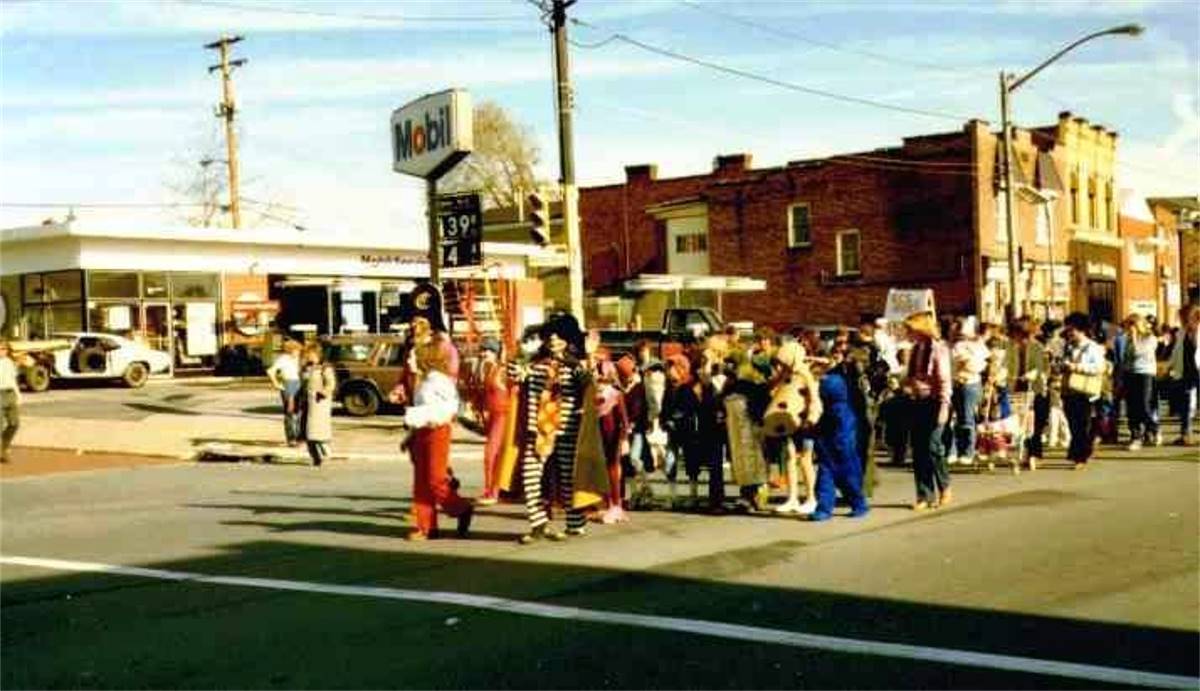

West Liberty Avenue at the junction with

Brookline Boulevard in 1915.

A single=track line was laid along West

Liberty Avenue in 1901 as part of the Charleroi Electric Short Line Railway.

The streetcar tunnel through Mount Washington opened on December 2, 1904,

bringing quick and reliable service to the South Hills.

In the spring of 1905 a double-track

line was constructed through Brookline from Kerr's Blacksmith Shop on West

Liberty Avenue (the Brookline Junction) to a dead end at Fairhaven Road

(Merrick Avenue). In 1910, the service was extended into East Brookline to

a trolley loop near Witt Street.

A trolley car heading inbound approaches

Pioneer Avenue in 1918.

Five years later, in 1915,

the entire West Liberty Avenue line was reconstructed. The modern trolley

service led to a dramatic surge in residential and commercial construction,

and a corresponding population boom.

An inbound 39-Brookline passes Birchland

as it approaches Breining Street after making the loop.

For six decades, streetcar traffic in Brookline remained a reliable transportation alternative. The Pittsburgh rail

network could get a passenger anywhere in the city. It was the prefered choice

for commuters traveling to work downtown, and students at South Hills High School

were issued passes for the trip to and from the South Hills Junction.

Pittsburgh Railways route 39-Brookline

remained in operation until September 1966, when the line was discontinued in

favor of Port Authority bus service. The route was renamed 41-Brookline. Although

they lack the nostalgia of the traditional streetcars, the bus service in

Brookline, and throughout the city, is still affordable and reliable. In 2011,

the Port Authority redesignated the Brookline

bus route back to the traditional 39-Brookline.

Light rail cars pass the Station

Square stop at Carson and Smithfield Streets.

For those who still enjoy riding the rails,

the Potomac Avenue "T" station in Dormont is a convenient nearby gateway to Pittsburgh's

modern light rail system. The "T" routes follow the old Mount Lebanon/Beechview and Shannon/Library

street car right-of-ways and connect to the downtown subway, then on to the North

Shore.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Are They Called

Streetcars or Trolleys?

There is some debate over whether the

proper term for the vehicles that ran the rails on Pittsburgh streets were

called "Streetcars" or "Trolleys."

The answer is ... both!

The official

terminology might sound a bit strange:

A TRAM (also known as a tramcar; a

streetcar or street car; and a trolley, trolleycar, or trolley car) is a rail

vehicle which runs on tracks along public urban streets (called street running),

and also sometimes on separate rights of way. Trams powered by electricity,

which were the most common type historically, were once called electric street

railways. Trams also included horsecar railways which were widely used in urban

areas before electrification.

For a more detailed history of trams,

visit Wikipedia (Trams).

Two inbound 39-Brookline streetcars, heading north

on West Liberty Avenue, approach the Capital Avenue Car Stop.

A Ride On The Brookline Trolley In

The Early 1900s

This account was published by

Mr. Donald Hahn, an old Brookline resident. Mr. Hahn details what it was

like taking the 39-Brookline trolley from the South Hills Junction through

to the old trolley loop. It is a wonderful look back at what Brookline

was like around 1910. It was copied from a Brookline Journal

article.

We are now aboard a Brookline

trolley car (Toonerville) at the South end of the tunnel (South Hills

Junction), for the trip to Brookline. We swing and sway down through the

barn yard to its end, and the switch.

Here the conductor got out, threw

a switch, and pulled onto the single track cutoff that leads to Warrington

Avenue. The conductor threw back his switch, and threw the light giving

right of way to the single track at the Old Bell House Tavern.

The Bell House stood just across Saw

Mill Run. An old wooden bridge spanned the run. Here the conductor turned off

the single light. Double track started here and we turn onto West Liberty

Avenue.

Born's West Liberty Hotel was on one

corner and Elijah Lee's blacksmith shop was on the opposite corner. Gilfillan

and Orr Feed Company was next to the hotel, and a frame house owned by Peter

Schaffner was across the street. From there up to Cape May Avenue just

a few frame houses stood.

West Liberty Avenue near the junction

with Saw Mill Run and Warrington Avenue in 1915, looking south.

At Cape May Avenue was the old

frame school. Here was were the Mission and Brookline Boulevard United

Presbyterian Church originated. A few more scattered houses, then the

Paul Coal Company mine entrance, stable and loading bins at the corner of

Stetson Street.

From here on more scattered houses,

with Zehfuss Hotel near Capital Avenue, Wilhelm's country store at Ray Avenue

and Butcher Baker's meat market at the corner of Pauline.

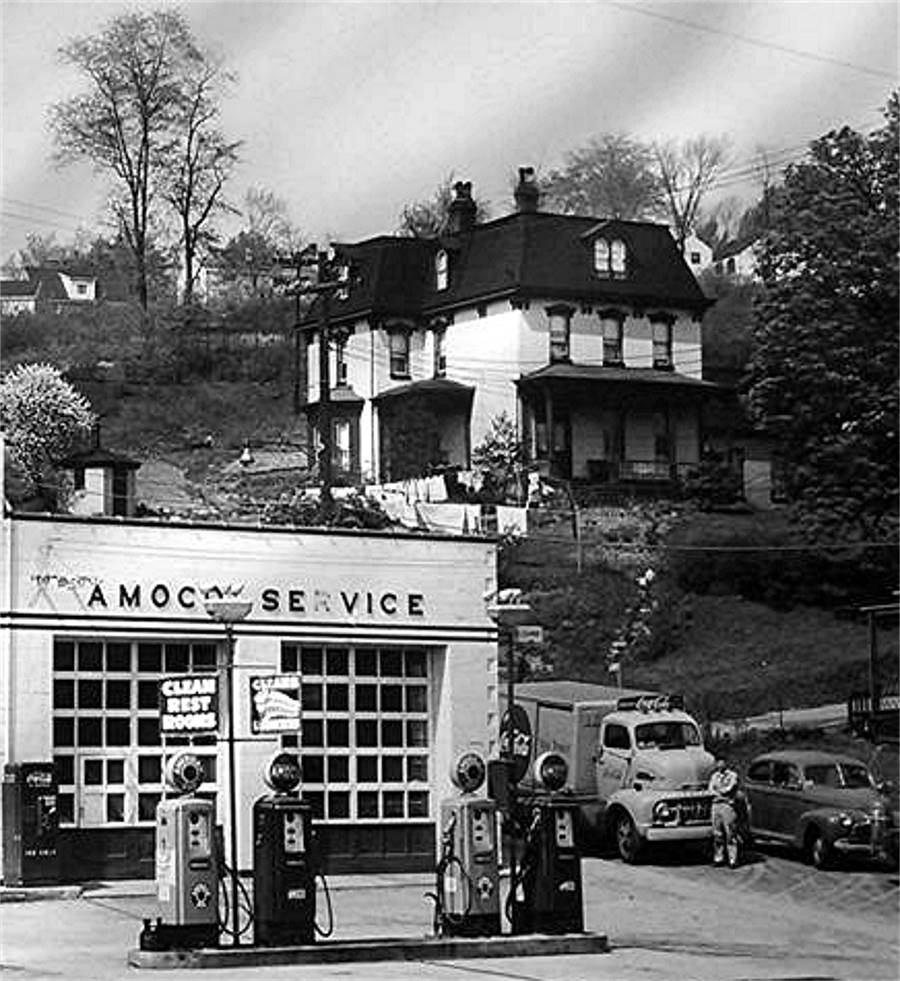

Where the Evangelical Home

stands were the Knowlson and Millitzer Farms, and at the junction the

George Kerr and Sons blacksmith shop, with the big house on the hill

behind.

Before we start up the hill let's

look back on the south-east side of West Liberty Avenue. On the corner

was the old mine entrance, the pumping station and air shaft.

The street car wound its way over

a private right of way up the hill. In later years the right of way

was widened and paved, extending the Boulevard to the Junction. Present-day Bodkin

Street was originally Hunter Avenue, then renamed Brookline Boulevard until

the paving of the right of way, at which time it became Bodkin.

We will now travel down the

Boulevard. The car tracks were in the center, a private right of way unpaved, and set between

the tracks were wooden poles. Long cross-arms were mounted atop these poles, to

which were strung the trolley wires.

I should state that Pioneer Avenue

was originally Lang Avenue, named for William Lang. The Lang farm was located

near the bottom of Pioneer Avenue, alongside the railroad tracks. When Brookline

was annexed into the city, the steet name duplicated another Lang Avenue and

needed to be changed. The residents decided to call the street Pioneer

Avenue.

Doctor C.C. Lang had his home and

office on the corner where Myer's Gas Station now stands. When Mr. Myer's

put in his first station equipment the house was moved to its present

site at Pioneer and Berkshire Avenues.

Looking up the lower end of Brookline

Boulevard towards Pioneer Avenue and the home of Dr. C.C Lang.

The streetcar exited the right of way onto the boulevard near the small

building to the right.

Next was part of an old orchard,

then W.H. William's Grocery. At the West Point trolley car stop (Wedgemere

Avenue), was Hoot's Bakery. This building housed many business establishments

until 1920.

Brookline's first movie house was

an open-air theatre between a store and the engine house. Crossing Castlegate

was Dooley's Grocery and Meats. Joe Dooley also had his own ice

plant.

Further along the Boulevard we pass

more vacant lots and the remnants of an another old orchard, until we reach

"Heine" Melvin's Drug Store at the corner of Stebbins. From a point opposite

Flatbush Avenue, a path cut through the field on an angle, ending beside Ed

Cook's house on Berkshire Avenue.

Brookline Boulevard on July 4, 1911,

looking northeast towards Stebbins Avenue and on towards Chelton (formerly

Chelsea Avenue) in the distance. Melvin's Brookline Pharmacy

is the first building on the right.

From Stebbins Avenue, more open

fields to McNeilly's Grocery. This building, now owned by Melman's,

housed stores operated by Dean Rhodes and Stevens. Every one of these

Boulevard stores had a stable on the alley to the rear.

The next buildings erected were

an apartment and duplex near Queensboro, where Dr. O'Hagan, the school doctor,

lived, and Sam Gigliotti's building. This building had two store rooms with

living quarters above. Sam had his tailor shop in one store. and Nick Ermilino

had a shoe repair shop in the other. Another early building was Bob Hartman's

News Agency and Simon Zitelli's Barber Shop.

In the triangle stood the frame

building owned and occupied by the Freehold Real Estate Company. Between

the triangle and Breining Street, Oakridge Street and Merrick Avenue was

an old orchard.

Brookline Boulevard in 1913, showing

the Freehold Real Estate office in area where the cannon sits today.

Beyond Breining Street to the right

we ran into, what was called in the olden days, Anderson's

Acres farm and

woods. To the left of the tracks was the Hayes farm. The original East Brookline

was laid out in part from the Hayes farm.

At Breining, the conductor threw a

switch and proceeded on single track to the loop, where he got out and threw

another switch for the return trip back up the boulevard.

I might add that for a few years

before the loop was built the streetcar line continued through the woods

and past the old coal mine shafts in the valley. It passed under a railroad

tressel and met up with the Charleroi line, then followed Saw Mill Run to

back to town.

<Ride The 39-Brookline And

See The Sights Along The Way - 1912>

City Steps

Another tried and tested way

to get from here to there in the community of Brookline is on foot.

Brookline has always been a walking neighborhood. Children make

their way to school every day along the broad sidewalks. Shoppers

walk to and from the boulevard pick up groceries, and commuters make

their daily trek to the bus or streetcar stop.

The Stebbins Avenue steps rise from

Berkshire Avenue to Woodbourne in 1933.

With all of the hills in

Brookline there are several roadways that in places are just

"Paper Streets." They are on municipal maps, but are in fact

long sets of City Steps. These cement staircases vary in length

from short climbs to long, mountainous ascents.

Some city steps run alongside

steep roadways, like the Belle Isle Steps and the Stebbins Steps.

Others are extensions of existing streets, such as the Jacob Street

Steps. The Ray Avenue and Wedgemere Place Steps are somewhat unique,

standing alone from beginning to end yet still carrying a distinct

street designation.

Looking down from the Brookline side

of the Jacob Street Steps as two men return home from work in

1952 (left),

and the Glenbury Street Steps, located at the bottom of the hill near the

railroad tunnel, shown in 1970.

Other city steps

in Brookline that are extensions of actual roads are along Stetson

Street, Kenilworth Avenue and Ballinger Street. At the bottom of Edgebrook

is a set of steps that lead to the South Busway and Timberland

Avenue. Another short set of steps connects Bodkin Street with

Pioneer Avenue.

Many of these steps have been

in place for over seventy years. They were constructed over time as

the community grew and expanded. Although they are showing signs of

age, the steps are still maintained by the city and remain popular

pedestrian transit routes to this day.

The Belle Isle Steps rise from Plainview

Avenue, shown here on September 18, 1934.

With communities like Troy

Hill, Mount Washington and the South Side Slopes, it may come as

a surprise to some that, as of 2012, Brookline boasts the two

longest sets of city steps. Ray Avenue ranks #1 with 378 steps

and Jacob Street ranks #2 at 364.

Brookliners who used

these long stairways during their daily commutes will always

remember how easy it was to get from the top to the bottom, and

how exhausting the climb could be going up in the opposite direction.

They were definitely a great way to get your exercise, and will

always be a memorable part of growing up in Brookline.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Brookline City Steps In 2013

Ray Avenue

The Ray Avenue Steps descend from Pioneer

Avenue all the way to West Liberty Avenue.

They are the longest municipal staircase in Brookline, with 378 steps in all.

A 1940 map showing the "paper street"

Ray Avenue.

The Ray Avenue steps stretch from West Liberty

Avenue at the bottom upwards to Woodward Avenue,

then through to Plainview, and finally to Pioneer Avenue at the

crest of the hill.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Jacob Street

Looking down the Brookline side of the Jacob

Street steps in East Brookline.

Looking up the Overbrook side of the

Jacob Street steps. The steps connect the two sections of Jacob.

Taken as one complete set of steps, the Jacob Street steps rank #2

in the city, with 364 steps in all.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Belle Isle Avenue

Two views of one section of the long Belle Isle

Steps that run from West Liberty Avenue to Plainview.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Edgebrook To Ballinger Street

and Timberland Avenue

Steps going up from Edgebrook Avenue to

Ballinger Street (left) and the South Busway and Timberland Avenue.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Wedgemere

Place

Looking at the Wedgemere Place Steps and

walkway from Gallion Avenue (left) and Berwin Avenue.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Stebbins Avenue and Bodkin

Street

Looking up the Stebbins Avenue Steps from

Berkshire Avenue (left) and the Bodkin Street Steps.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Stetson Street and Kenilworth

Avenue

A section of the Stetson Street Steps (left)

and the Kenilworth Avenue Steps leading to Aidyl Avenue.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

Stapleton Avenue and Repeal

Way

The Stapleton Avenue Steps off West Liberty Avenue

(left) and the Repeal Way Steps looking up from Glenarm Avenue.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

In Nearby Overbrook Along Glenbury:

Pinecastle Avenue and Fan Street

The Pinecastle Avenue steps at the bottom

of Glenbury Street, next to the railroad tunnel.

The Fan Street Steps that lead from the

intersection of Seldon Street and Seldon Place down to Glenbury.

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

<><><><> <><><><>

At one time, the City of Pittsburgh

had over one thousand sets of city steps dotting the urban landscape. In 1945

there were over fifteen miles of steps in service and the city employed an

Inspector of Steps.

As of 2012 there were 712 of these

staircases still in use. Some of the older steps that are no longer in

existence were much longer, and steeper, than any encountered in

Brookline.

The grand-daddy of all Pittsburgh

City Steps would have to be the 1000-step, mile-long Indian Trail Steps, shown below in 1910. The legendary wooden staircase scaled

the northern slope of Mount Washington from Carson Street to Duquesne

Heights from 1909 to 1935.

Freehold Real Estate Company

The Freehold Real Estate Company was

formed in 1904 after taking over the firm Haas and Lauinger, and was the

largest real estate vendor in Western Pennsylvania. H. P. Haas, president of

the company, which was headquartered on Fourth Avenue, Pittsburgh, was instrumental

in having a plan of lots laid out in West Liberty Borough, in 1905, which he

called Brookline. The family of H.P. Haas, a resident of the East End, enjoyed

the Brookline atmosphere so much that four brothers, Henry T., William F., C.A.

and George R., were some of the first lot buyers, with homes built along

Woodbourne Avenue.

The following farms were bought by the West

Liberty Development Company for this purpose: Jane Reamer, Willison Hughey, David Hunter, Richard Knowlson, Tom Knowlson, John Knowlson, William McNealy

(Chimney Town), Philip Fisher, Dr. J.H. Wright, Joseph McKnight, John H. Daub

and Philip Linn. The Paul Land Company developed over 140 acres of farmland owned

by Elizabeth Paul. H. P. Haas also handled the development of portions of the Ida

Fleming and Joseph Hughey estates as early as 1902 with Haas and

Lauinger.

The next problem was that of water

supplies. In 1905 the South Pittsburgh Water Company had a large wooden

tank supported high in the air near Neeld Switch. Pipe lines were laid from

this water tank. When the South Pittsburgh Water Company changed the

location of their water plant, the old tank stood for many years after its

abandonment and became sort of a land mark to the locals. The foundation

markings remain to this day. Street improvements and sewerage were provided to

take care of the influx of new residents.

The downtown Freehold Real Estate offices at

334 (left), in 1907, and later 311 Fourth Avenue, in 1915. These offices

handled many of the investment and home buying transactions for

Brookliners in the early days.

When the necessary infrastructure

was in place, the West Liberty Development Company began developing the

lots for the expected rush of new residents. The Freehold Real Estate Company

erected a small office at

the intersection of Brookline Boulevard, Chelton and Queensboro Avenues, on

the small triangular island.

From this central location, most real

estate transactions regarding Brookline properties took place.

Further development in East Brookline (Overbrook) kept the Freehold Real

Estate office busy for over two decades. The construction of

the Liberty Tunnels in

1924 led to another properous time for the company. New home sales hit record

highs.

Real Estate brochure from the

early-1920s.

The Great Depression caused a decline

in the housing market, forcing the Freehold Real Estate Company to close their

Brookline office in 1932. The company had overseen the development of the

community for over a quarter of a century. The triangle where the

office stood was later converted into a small park and the Brookline Veteran's Memorial.

First Churches

The first church in Brookline was

a stump church at the end of Brookline Boulevard. People gathered around the

preacher and sat on log stumps to hear his Gospel stories.

In 1868 the Knowlson Methodist Church

was constructed. This first church building stood near the present-day junction

of West Liberty Avenue and Brookline Boulevard. The property was donated by

Richard Knowlson.

In 1905 the church united with the

Banksville Methodist Church and Reflectorville Methodist Church. The congregation

formed the Brookline Methodist Church, chartered in 1913. Their church was constructed

along Brookline Boulevard, at Wedgemere Avenue.

The old Knowlson Methodist Church,

built in 1850 above the junction of Brookline Boulevard and West Liberty Avenue,

shown here in 1915. The church was used over the years by the Brookline Methodists,

the St. Mark's Lutherans,

and the Brookline Presbyterians, all of whom later relocated to larger churches

built along Brookline Boulevard.

A small group of United

Presbyterians had a

small house of worship, erected in 1902, near the Bell House on West Liberty

Avenue. In 1907, they moved to the West Liberty Elementary schoolhouse

on Pioneer Avenue, then to the old Knowlson Church for a few years.

The Presbyterians constructed a new

church at Queensboro and

Brookline Boulevard, dedicated on February 13, 1913. The church was enlarged

in 1924, and again in 1953.

Resurrection

Roman Catholic Church was

organized in 1909. Construction of a church and school along Creedmoor Avenue

began in 1910. The original building was completed in 1912, then enlarged in

stages through 1928.

Masses were held in the basement of the school building from 1910 through 1939, when a separate church was built next door. Over

the years, the congregation at Resurrection grew to such proportions that four

individual spinoff parishes were formed, including St.

Pius X on

Pioneer Avenue near McNeilly Road, and Our Lady of Loreto, on Crysler Street near Moore Park.

Other spinoff congregations include St. Bernard's in Mount Lebanon

and St. Norbert's in Overbrook.

Resurrection Church in 1910, the year that

the new church and school building was completed.

St. Mark

Evangelical Lutheran Church was organized in 1906 as a mission in a small

chapel on Bodkin

Street (formerly Brookline Boulevard) with a membership of only twelve people.

It's congregation flourished, and in 1928 a new

church was constructed at

the corner of Glenarm Avenue and Brookline Boulevard. The church was enlarged

in the early 1960s.

The Pittsburgh Baptist Church is located on Pioneer Avenue near McNeilly Road and is home

to Pittsburgh's Southern Baptist community. The congregation has been in existence since

1958 and have been holding services in the old Brookline church since April of

1959. The church building itself was originally known as the Grace

Lutheran Church, home the Missouri Synod congregation. The inner sanctuary

is steeped in Lutheran symbolism. The building dates back to the early

1900s.

The Episcopal Church of the Advent, with

its conical bell tower, stands atop the high ground along Pioneer

Avenue at Waddington. The large home is the Fleming estate. Ida Fleming helped

to form the church

along Pioneer in 1904. The homes in the foreground of this 1935 photo are

along Aidyl Avenue.

The Church of the

Advent Episcopal was

organized in 1904 and a small church built on Pioneer Avenue, near the

intersection with McNeilly Road. Additionally, there was the Paul Presbyterian Church, built in 1923 at Dunster Street and Pioneer Avenue on land donated

by Elizabeth Paul.

In the 1960s, a new denomination moved

into Brookline. The Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses built a house of worship

along the lower part of Brookline Boulevared, at the intersection with Witt

Street. The Jehovah's left at the start of the 21st Century. Since then the

small church has served non-denominational Christians. It was briefly called

the Agape Church, GracePointe and Upper Room Worship. Today it is home to

Sion Iglesia Christiana.

Educational Institutions Formed

The first log school house was built in

1807, located near the Lutheran Church in Baldwin Township. The oldest school in

the Brookline area, according to Professor Joseph F. Moore, was situated on Pioneer Avenue near Ray and

Holbrook Avenues. Another was located at the corner of Cape May and West Liberty

Avenue (the original West Liberty School).

A third was the East Side School, a frame

building on Edgebrook Avenue, and the fourth was a private school at the south

end of the present Liberty Tubes, built in 1820 by Mr. William Dilworth, an early

coal mining entrepreneur, for the children of the coal miners he

employed.

The second West Liberty Elementary School

building, built in 1898, is shown here in 1941

after it was converted to Elizabeth-Seton High School.

In 1898, a modern four-room schoolhouse,

called West Liberty Elementary School was erected on Pioneer Avenue near the intersection with Capital.

Avenue. Known as the "Little Red School House", the building was enlarged in

1906 to eight classrooms.

Soon, overcrowding at West Liberty

Elementary compelled the Pittsburgh Public School Board to build Brookline Elementary School, located at Pioneer and Woodbourne Avenues. The original four-room

building was dedicated on July 4, 1909. Six additional classrooms were added

in 1913, followed by six more in 1920. Another wing, including nine rooms and

other amenities, was constructed in 1929.

The Brookline Elementary School basketball

team in 1913.

In addition to the public schools,

parochial school children could attend Resurrection Elementary School, which was constructed between 1909 and 1911. The school, located on

Creedmoor Avenue, opened for students in the fall of 1912. Overcrowding at Resurrection led to the formation of St. Norbert's parish

in Overbrook (1914) and St. Bernard's parish in Mount Lebanon (1919).

Alice

M. Carmalt Elementary School was

built in 1937, along Breining Street, and expanded in the 1950s. Continual population

increases led to several expansions of Resurrection, and the formation of two other

Brookline parish schools, St. Pius X in 1955 and Our Lady Of Loreto in 1961, both located along Pioneer Avenue.

The Eighth Grade graduating class from the

1913-1914 school year at Resurrection Elementary.

Other educational institutions

included DePaul Institute, built

in 1910 for the hearing impaired, Toner Institute, a

military type training academy for orphans that was chartered in 1941,

and Pioneer School,

constructed in 1958 and operating as a special education facility to meet the

needs of the physically challenged.

The old West Liberty School was sold

in 1938 to the Catholic Diocese for use as a girl's high school,

called Elizabeth Seton High School. A newly constructed school building, the third version of West

Liberty School opened at Crysler and LaMoine Streets in 1939.

The school was expanded in 1959. West Liberty School was again closed in 1979,

then reopened in 2000, after an additional wing was built.

West Liberty Elementary School in 1959,

after an expansion of the school building.

In 1996, in response to the financial

difficulties in supporting three aging schools, and a overall drop in enrollment,

the Catholic Diocese merged the three local parochial elementary schools,

Resurrection, St. Pius and Loreto. Located in the old St. Pius school building,

the school was called Brookline Regional Catholic from 1996 to 2014. It was

designated as Saint John Bosco Academy in 2014 and closed in June 2019.

High Schools For

Brookliners

Beginning in 1900, students graduating

from West Liberty Elementary School were permitted to attend Knoxville Union

High School at no charge, largely due to Professor Moore's efforts in obtaining

the right of West Liberty Borough children to free public education.

Beginning in August 1917, most Brookline

students attended South Hills High School, located in Mount Washington, for their secondary

education. South Hills High School served local students for sixty years. In 1977,

Brookline students were transferred to the newly constructed Brashear High School

in Beechview.

South Hills High School, shown here in

1939, served Brookline students from 1917-1977.

For a parochial secondary education, from

1912 through 1934, Resurrection Elementary also offered high school classes to

parish graduates. From 1935 to 1991, girls could attend St. Francis Academy in

Castle Shannon. Beginning in 1941, another alternative for the ladies was

Elizabeth-Seton High School on Pioneer Avenue.

For the boys, South Hills Catholic

High School, located on McNeilly Road, opened in 1960. The institution merged

with St. Francis and Elizabeth-Seton after the completion of the 1979 school

year to form the present-day Seton-Lasalle High School.

Rumble Of The Railroad

Just like the steel mills and factories

that lined the Three Rivers in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Pittsburgh was also

synonymous with the railroad industry. Local small-guage coal railroads were

active in the South Hills as early as 1861. The Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad operated continuously along Saw Mill Run

from 1871 to 1912.

In the city, the nation's larger railroads

were one of the major industries in the city. The Pennsylvania Railroad, the

Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad and the B&O Railroad all had huge facilities

within the Golden Triangle competing for their share of the lucrative passenger

and freight business.

Workers working on the West Side Belt

Railway line, part of the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railroad,

near Timberland and Cadet Avenues in 1909 (left), and the rails

as they

pass under the Timberland Avenue Bridge in 1918.

Another major railroad that was

once a part of Pittsburgh's heritage was the Wabash Pittsburgh Terminal Railway. The Wabash was built to compete with

the Pennsylvania Railroad for the lucrative steel hauling business. It

opened in 1904 and went bankrupt in 1908.

Part of the Wabash network was the

old West Side Belt Railway line that skirted the border of Brookline,

heading along Saw Mill Run valley, then following the Library Road

corridor through Castle Shannon and continuing west. Although the Wabash

was in receivership, this spur line was upgraded in 1909 and

continued to be a profitable freight-hauling venture.

Pittsburgh & West Virginia Railroad

train at Elm Street in Castle Shannon in 1940 (left) and

crossing the tressel at Whited and Jacob Streets in Brookline, March

1957.

In 1928 the line was purchased by

the Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railroad. P&WVRR locomotives passed